Q: Do all African Americans have slave ancestry?

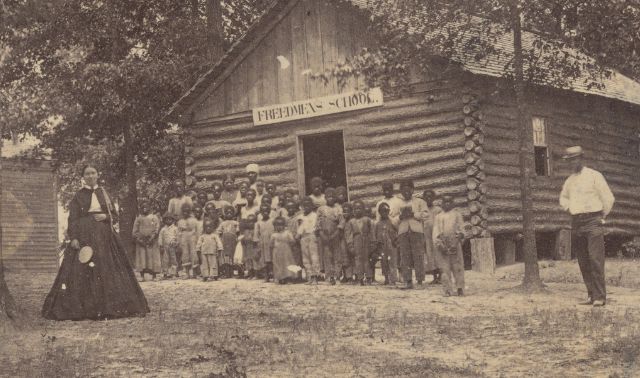

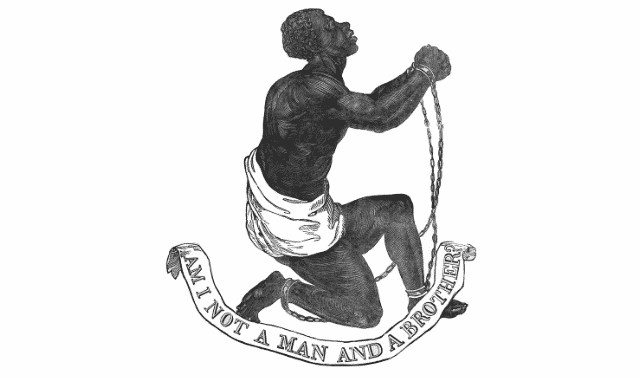

A: At first glance, this seems like an easy question to answer, but it’s really as complex as the concept of slavery. The slave trade in North America began when the first Africans came to Jamestown in 1619. Most were in some form of servitude, whether as indentured servants or slaves. Indentured servants were debt bondage workers under contract for three to seven years. Slaves were under the control of another person for life.

The importation of slaves was banned in 1808, but slavery continued in the United States until emancipation in 1865. Most slaves were taken to North America from West and Central Africa, an estimated 450,000 before 1808. (Another 2 million Africans died in the Middle Passage, the voyage from Africa to North America.) To learn more about the Atlantic slave trade, visit the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database.

According to the US Census Bureau, an African-American is a person with origins in any of the black racial groups of Africa. It includes people who indicate their race as “Black, African Am. or Negro,” or provide written entries such as African-American, Afro-American, Kenyan, Nigerian or Haitian.

For example, former president Barack Obama’s mother is of European ancestry and his father is of Kenyan ancestry. Obama is routinely identified as the first African-American president, and his father’s ancestors were not slaves. African-Americans whose parents immigrated to the United States from Africa after the time of slavery likely do not have any slave ancestry.

If your ancestor was born in the United States during the time of slavery, you’re more than likely a descendant of slaves. Slaves were able to obtain freedom through manumission or purchase. Freed slaves often carried their manumission papers with them when they traveled—some states even required registration with the county courthouse. To determine if your family was free or slave, review the census records and courthouse records for your home state.

Answer provided by Kenyatta D. Berry

A version of this article appeared in the December 2009 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: I’d like to know how to find where free African American families came from.

I can trace ancestors to Maryland and North Carolina, and found them listed in Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina from the Colonial Period to About 1820 by Paul Heinegg. These people were landholders, too.

A: The major challenge facing anyone researching African-American ancestors is finding them during their years in slavery. This applies to those who were free before the Civil War and those freed by the Civil War. Since many African-Americans free before the Civil War were former slaves, your research strategy for finding pre-Civil War and post-Civil War free ancestors is basically the same. Different research strategies come into play when you start looking for ancestors in slave records.

Because you have information that indicates your ancestors were free before the Civil War, your search for them as free people would start from the date of the research you have, and move backward through records typically used in genealogical research. That includes federal, state and local government records such as census, marriage, land, probate, tax and any other private records that may have been recorded in your ancestors’ names.

You also may find pre-Civil War documents that apply specifically to free people of color, which may provide clues to where an ancestor came from before acquiring his freedom. Included among these are manumissions (court records created when a slave was freed), registers of free blacks, guardianship records and special tax records. Some county courthouses keep these among probate or deed records; others file them separately. These older records also may have been forwarded to a state archive.

When you can no longer trace your ancestors in free records, you’ll have to identify their slaveholder in order to search for them as slaves. For more information, look for the book A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your African-American Ancestors.

Answer provided by Franklin Carter Smith; August 2008

Q: Recently, to my dismay, I found that my ancestors owned slaves. I’ve come across data about those enslaved that might be useful to their descendants. Is there an appropriate way to share this?

A: In a Q&A with The Root, “Finding Your Roots” host Henry Louis Gates Jr. offers some suggestions. Start with Ancestry.com, which has several relevant message boards, and the forums at AfriGeneas. Next, explore historical and genealogical societies in the area where your ancestor lived. These organizations may have projects that compile this sort of data. FamilySearch is also reportedly exploring ways to incorporate such information in its family trees.

For now, the closest thing we’ve found to a site that is specific to what you describe is the Slave Name Roll Project. It includes user-submitted documents, such as wills, with information on those enslaved.

The Bittersweet Blog shares stories of “linked descendants,” people who have a joint history in slavery—a pairing of a descendant of an enslaved person with a descendant of his or her slaveholder, who have found each other and who are in communication.”

The blog is associated with Coming to the Table, an organization that aims to promote racial healing through national gatherings and training workshops. Among the group’s efforts is the book, Slavery’s Descendants: Shared Legacies of Race and Reconciliation (Rutgers University Press).

You can also search the web for state-specific projects such as the Texas Slavery Project, which is compiling a database of Texan slaves and slaveholders during the Republic era (1837–45), and Low Country Africana, which is compiling a database of slaveholders in South Carolina. The Virginia Historical Society has an ongoing project, Unknown No Longer, compiling the names of slaves.

The site Reclaiming Kin echoes Gates’ advice to share your finds with “the library, state archives and genealogical society of the location where the farm/plantation was located.” The site also offers these words of wisdom for descendants of slaveholders: “We are very clear that you did not own any slaves. We do not hold you personally responsible for holding slaves, any more than we hold ourselves responsible for the reprehensible things any of our ancestors did. The past comes with the baggage of both good and bad. It shows us all how human we are.”

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2019 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: Where can I find information on descendants of John Brown, the abolitionist, who came to Virginia and then to South Carolina?

A: John Brown fought his own “holy war” for the abolition of slavery, and his immediate descendants fought at his side. Born in Torrington, Conn., in 1800, he was descended from abolitionists who had many children. He had two wives and a total of 20 children, although many did not survive to adulthood. With first wife Dianthe Lusk, he had John Jr., Jason, Owen, Frederick, Ruth, and Frederick II. Dianthe died in childbirth in 1832, so he married Mary Ann Daly in 1833. She bore Watson, Salmon, Sarah I, Charles, Oliver, Peter, Austin, Annie, Sarah II, Ellen I, Ellen II, and Amelia. John Brown was such a dedicated abolitionist that he sometimes lived among African Americans to help them, and he brought his children and in-laws into his exploits.

Two events highlighted Brown’s activism. In Kansas in 1856, his supporters—including some of his sons—murdered some pro-slavery settlers in revenge for a recent raid on an abolitionist town. In 1859, his group raided the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry (Virginia, now West Virginia), expecting to arm a slave rebellion. Thwarted, Brown was hanged for treason and became an abolitionist martyr. Some of his sons died in his raids, but both sons and daughters spawned descendants. For the Brown family history, see Gerald McFarland’s A Scattered People: An American Family Moves West (Ivan R. Dee), especially his source note. This book will also serve as a model for developing Brown family narrative in historical context. Also, contact the Hudson (Ohio) Library and Historical Society and see “The Wives and Children of John Brown” from the National Park Service to learn about son Owen Brown.

For more on Brown’s life, see the website of the PBS documentary “John Brown’s Holy War”, as well as biographies such as Warren and Stephen Oates’ To Purge This Land with Blood: A Biography of John Brown (University of Massachusetts Press) and websites such as The John Brown Raid Headquarters. There is also a well-regarded novel dramatizing Brown, Cloudsplitter by Russell Banks (HarperCollins). Recently, the Brown family Bible, including family information dated 1839, was restored to its special case at the Harper’s Ferry museum. For a discussion of “The Madness of John Brown” and whether his family line carried insanity, see the chapter by that name in James West Davidson and Mark Hamilton Lytle’s After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection (Knopf). If your family is related to John Brown’s, you have a wealth of family and historical material to access, including pivotal, dramatic events in American history.

Answer provided by Katherine Scott Sturdevant