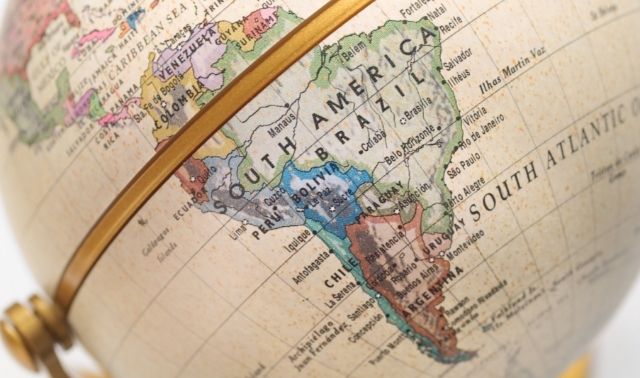

If you’d like to investigate your family history in Brazil or elsewhere in South America, you’ll be happy to know that genealogy there doesn’t have to be difficult. Digitization projects, notably by FamilySearch, have put millions of South American documents within easy reach online. (You also can search many of these databases at Ancestry.com, and some via MyHeritage.) You can get a good start on your South American family tree before ever squinting at microfilm—and when it does come time to scroll those rolls, you’ll find even more ancestral answers.

South American naming traditions

Step one in training to be a South American genealogy champion is understanding the names you’ll find. Although the borders of South American nations were fluid for a long time, the essential divide in the continent is between Brazil, where Portuguese is spoken, and the other, Spanish-speaking nations. In the Portuguese tradition, people often use compound surnames, combining those of the mother and father, with or without a preposition (de, do, da, d’). In names such as Maria Costa Silva or José João Ferreira de Castilhos, the first surname is typically the mother’s, followed by the father’s. Historically, however, surnames might represent the more prominent family or derive from grandparents instead. In the early 1800s, boys typically took their fathers’ surnames and girls, their mothers’.

Maiden and surnames in Brazil

Until about 150 years ago, Brazilian women kept their maiden names unchanged when they married. Recently, the practice has been to attach the husband’s surname, with the preposition de, so someone marrying a Silva would add de Silva. Widows became, in this case, Viúva (widow) de Silva.

Expect the worst when searching for surnames in Brazil, because last names might have a half-dozen variations depending on the record—especially for women. The FamilySearch research guide for Brazil warns, “It is therefore sometimes necessary to give up the idea that the father’s last name is always a certain name. Instead, you might need to note all persons with the same first name to learn the variations within the records.”

Spanish naming traditions, used elsewhere in South America, may vary by country but generally follow a slightly different compounding system, with or without a y, a dash (-), or a preposition (de, del, de la). Here, the pattern is reversed from the Portuguese, with the paternal surname first and then the mother’s: Maria Garcia Fernández de León, José Juan Garcia y Rodríguez. As in Brazil, however, surnames might come instead from grandparents or the more prominent family.

Names in Spanish-speaking South America

Like their Brazilian neighbors, women in Spanish-speaking South America began taking their husbands’ surnames at marriage about 150 years ago. Recently, the pattern is similar to Brazil, attaching de plus the husband’s name in place of the maternal surname. If María Josefa Torres Sepulveda married a man named Martínez, she would become María Josefa Torres de Martínez. Juan Silva’s widow would be Viuda de Silva.

In countries like Peru, which saw a lot of foreign immigration, you’ll find many surnames from other ethnicities: Fujimori from Japanese, Arizmendi from Basque, Benalcázar from Arabic and so on.

You may have noticed that our name examples often include María (unaccented Maria in Brazil) for women and José for men. As in Spain and Portugal, children were usually given several names at baptism, one of which often honored of Jesus’ parents, Mary and Joseph. A second name might derive from the saint on whose day the baptism fell. Children might never be called by these baptismal names (nombre de pila in Spanish), but rather by another given name.

Church records

Step two toward gaining your genealogy champion status is to consult church records—the first records you’ll want to search. Until modern times in most countries, even if your ancestor was of a different religion, he would nonetheless be listed in Catholic records, which date to the Council of Trent in 1563. In Chile, for example, Roman Catholicism was the official religion until 1925 and the church recorded almost every Chilean until 1885. Argentina, whose first diocese was established in 1547, relied exclusively on church records until 1886. From the Spanish conquest of 1532 to the Constitution of 1920, Catholicism was the only religion accepted in Peru, which didn’t begin civil registration until 1886. Although Brazil had a more varied religious history, including an early arrival of Jews, civil records didn’t begin until 1850.

Even when researching dates after civil registration of vital records began, you should continue to use church records to double-check accuracy and fill in gaps. FamilySearch now boasts many digitized and indexed church records from South America, along with still more that are online but must be browsed. For Argentina, for example, you’ll find a

collection of nearly 1.5 million baptisms dating from 1645, plus church records from Buenos Aires and elsewhere. Scroll down at FamilySearch for another 15 browseable church records collections. Even less-well-covered countries such as Bolivia enjoy a large database of nearly 3 million baptisms as well as smaller files of marriages, deaths and other church records.

If the records you want aren’t online yet, search the FamilySearch catalog for your ancestor’s country and town, and look under the Church Records category to find microfilm you can borrow for a fee through your local FamilySearch Center or view at the Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City.

FamilySearch catalogs church records by town, but you’ll also need to know the parish within that place where your ancestor lived, if your ancestor came from a city with multiple parishes. In very large cities, keep in mind that families might go to the main cathedral for a baptism or other ceremony.

If FamilySearch hasn’t microfilmed records from your ancestor’s parish, you’ll need to write to the place in South America where they’re kept. This may be the local parish or a diocesan archive, depending on the country and the time period. Consult the research guides for your ancestral country found in FamilySearch’s Wiki. You’ll also find letter-writing guides for Spanish and Portuguese on FamilySearch.

Church record search strategies

These methodical search strategies will come in handy for using church records to find your South American ancestors:

- Search for a baptismal record for one ancestor. When you find it, search for the baptisms of brothers and sisters.

- Estimate the parents’ marriage date based on the birth of the first child, then search for a marriage record. It’ll often have clues, such as birth date and parents’ names, to help you find the couple’s baptismal records. If not, search using an estimate of their ages, or ages gleaned from death records.

- Once you find the baptismal record for the husband or wife, repeat the process, looking for siblings, then the parents’ marriage.

- Search in records of neighboring parishes if you find that an earlier generation is missing.

- Search death registers for all family members.

Civil Records

Now that you’re hitting your research stride, consider civil registrations. More recent ancestors may be found in these records, which generally began in the second half of the 19th century throughout South America. Brazil was the first, in 1850, and a few didn’t begin until the 20th century, such as Ecuador in 1901 and Bolivia in 1940 (see box, below.) Even after the official beginning of civil registration, it typically took several years for the law to be universally observed; Argentina, for example, instituted civil registration in 1886 but full compliance lagged until about 1900. On the other hand, some localities started keeping their own vital records early, and these are included in FHL collections.

Details included in civil registrations vary by country, but generally these records cover births, marriages and deaths. Divorces were rare and may be recorded in court documents instead. As civil registration became more established, the amount of information in these records often expanded.

Birth records

Birth records typically include the child’s name, the date and time of birth, names of parents, the town where the birth occurred, and the address of the house or hospital where the birth took place. Family information may include the age of the parents, their birthplaces or residences, marital status, professions, and the number of other children born to the mother, as well as information about grandparents.

Marriage records

Early marriage records might give only the names of the bride and groom and the marriage date. Later records might include the ages of the couple, their occupations, residence and birthplaces. You could even find the names and birthplaces of their parents and grandparents, enabling you to jump back long before the start of civil registration.

This is also true of early death records, because they cover individuals who were born and married before the start of civil registration. Here you might find the person’s name, date and place of death, and information about the deceased’s birth, spouse, children and/or parents. Keep in mind that such details can be unreliable, since they depend on the recollections of others.

FamilySearch has microfilmed many South American civil registration records and put some online, either indexed or browseable. For Brazil, for example, indexed collections include Rio de Janeiro and Pernambuco and image-only collections are available online for the states of Paraná, Paraíba, Piauí and Santa Catarina. Records not yet online, but available on microfilm, cover the states of Ceará, Alagoas, Bahia, Minas Gerais, Pará, São Paulo and Rio Grande do Sul, along with some for Rio Grande do Norte and Sergipe. Search the FamilySearch online catalog by the name of your ancestor’s town or municipality, such as: Brazil, [state], [town]—Civil Registration or Chile, [province], [municipality]—Civil Registration.

If the civil registration records you need aren’t on microfilm, you’ll have to figure out where they’re kept. Most often this is in a local office in your ancestors’ town. In Peru, for example, records are at the local civil registration office (Oficina del Registro Civil) in each municipality; duplicates are at the Supreme Court of Justice (Corte Superior de Justicia de la República) in Lima. Similarly, in Argentina, although there’s no central repository, duplicates are maintained in each provincial archive.

Some countries, including Argentina, also have indexes to civil registration records. Check the country-specific research guides in the FamilySearch Wiki for details.

Civil registration start dates

- Argentina: 1881

- Brazil: 1850

- Bolivia: 1940

- Colombia: 1865

- Chile: 1885

- Ecuador: 1901

- Paraguay: 1880

- Peru: 1886

- Uruguay: 1879

- Venezuela: 1873

Immigration records

Once you’ve begun to research your ancestors in South America, you’ll want to explore how they got there (and where they went). Here the differences between the nations of South America are more pronounced, varying historically by their settlement patterns and openness to immigrants.

Brazil

In Brazil, for example, although people had been coming from Portugal since the 1530s, general immigration began only after a royal decree in 1808 opened the ports to direct trade with other countries. Immigration was only a trickle, however, until slavery was abolished in 1888 and plantation owners needed fresh labor. After the US Civil War, many Southerners emigrated to Brazil, only to later return to the United States. Some 2.5 million immigrants arrived in Brazil between 1889 and 1913. Most arrived at one of three ports—Rio de Janeiro, Santos (port city for São Paulo) or Salvador; FamilySearch has microfilmed records from all three, and some records for Rio de Janeiro and Santos (São Paulo) are available on FamilySearch. These were also the chief ports for emigrants leaving for destinations such as the United States.

Peru

Peru has a varied immigration history. Before 1775, when a royal decree loosened rules governing emigration from Spain, most came to Peru from Castilla, Andalucía or Extremadura. These records may be found in the General Archives of the Indies (Archivo General de Indias) in Seville, Spain. In the mid-1800s, however, Chinese immigrants began to arrive to work on the guano deposits of the Chincha Islands and on the railroads. Later, Peru became a major destination for Japanese immigrants; sources in Japan are the best way to trace these ancestors. The main port of entry in Peru was Callao, but none of those passenger lists has been microfilmed.

Emigration from Peru to the United States began earlier than in other South American countries, with some going to California in the gold rush years. Numbers were small, however, until after World War II, when many Peruvians left for California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia.

Argentina

Another country with a varied immigration pattern, Argentina recruited immigrants after independence. A commission organized in 1824 advertised to foreigners and offered free land, tools and animals to arrivals who’d work on the land for five years. Irish and Basque were among the first to take this deal. In the 1850s, new offers brought immigrants from Switzerland, Italy’s Piedmont, the Haute-Savoie and Savoie departments in France, Russia and Germany. Between 1870 and 1890, 1.5 million immigrants arrived, including groups from Wales and Jewish refugees from Russia.

Most immigrants arrived at Buenos Aires or at Montevideo in Uruguay and crossed the border. Passenger lists and some passport records for Buenos Aires survive (except for 1870 to 1888), and some have been microfilmed; these also include embarkation records. The Center for Migration Studies (Centro de Estudio Migratorios) has computerized records from 1888 to 1925, and you may write this organization for information. Its website Cemla is in Spanish; visit in Google’s Chrome browser to read it with Google Translate.

FamilySearch coverage of South American immigration and emigration records is spotty, but it’s worth checking the FamilySearch online catalog wherever your ancestors lived. Look under the country and/or town name, and the Emigration and Immigration category.

Other Genealogy Records

What if you’ve exhausted church and civil registration records in your quest for South American ancestors? Here’s where it gets tricky. Many resources that are familiar to US researchers—censuses, wills, land records, military records—are less useful in South American genealogy. They may not have been created at all, as is the case for some censuses, or they require considerably more effort to access. Although FamilySearch has microfilmed a few of these record types for South America, you may have to write to local offices or archives, or visit in person.

Census records

In Brazil, once statistical information had been compiled from censuses, the original returns were mostly destroyed. A few enumerations still exist at regional archives, and there were also ecclesiastical censuses that may be found in diocesan archives. Some states, notably São Paulo, conducted their own censuses in the late 1700s and early 1800s; these primarily are available only in state archives (find contact information for each state’s archive) and only a few are on microfilm at the FHL.

The census story in Argentina is a little better, though these enumerations should still not be your first choice for research. National censuses taken in 1869 and 1895 are searchable on FamilySearch; the 1914 census is available only at the Argentinian National Archives (Archivo General de la Nación) in Buenos Aires.

Chile took a series of censuses beginning in 1813, but only a few have been microfilmed. In Peru, some municipal census images from 1831 to 1866 for Lima are available to browse at FamilySearch. Experts advise using church and civil registration records first, in both Chile and Peru, as well as elsewhere in South America.

Wills and probate records

Wills and probates, although extensively recorded, are challenging to access throughout South America because notaries kept them. In Peru, for example, notarial records, including wills and estate papers, date as far back as 1534. If you can find them for your family, they may include birth and death information predating civil registration. Unfortunately, few South American notarial records are microfilmed, and they can be complex.

Your best bet is each country’s national archive: In Argentina, for example, the national archives has notarial records from 1584 to 1756, organized in chronological order as well as by notary. In Peru, the law requires notarial records to be deposited in the national archives after 30 years. But in Brazil, notarial records dating back to 1549 are housed in public archives (arquivos públicos) spread throughout the country.

Land records

The story is similar for land records. Although they date back to the earliest days of European conquest and settlement—1528 in Peru, for example—land records haven’t been widely microfilmed and must be accessed at national and other archives. Those earliest records from Spanish-speaking areas are in Spain, at the National Archive (Archivo General de la Nación

Among Brazil’s most valuable early genealogical records are the land grants (sesmarias) collected in 5,000 volumes in the national archives. Covering 1590 to 1830 for the state of Rio de Janeiro, they contain information similar to that in inheritance records, including the names of spouses and children, residences, dates and relationships.

Military records

Although South America’s various wars barely make it into US history books, they led to a wealth of military records. Because FamilySearch has microfilmed few of these, however, they can be tricky to get. You’ll typically have to contact the country’s military archive.

In Brazil, military records begin about 1750. Beyond information about an ancestor’s military career, they usually include his age, birthplace, residence, occupation, physical description and family members. You’re more likely to find such details about an officer than an enlisted man.

Military records in Peru, which was involved in a series of conflicts and battles from the 1500s to as late as 1942, begin about 1550. Most are at the country’s national archives, historical military archives, and national library in Lima. You’ll need to know the unit your ancestor served in, which you might be able to guess based on his hometown when he was of age to serve.

Most records for the Argentine military are at that country’s Army Historical Archives (Archivo Historico del Ejercito). The provincial archives may also have some of these records as well. The FHL has some provincial records; check the FamilySearch catalog. For Chile, look for military records at its national archives.

Cemetery records

Finding South American cemetery records typically requires identifying the place of burial and then contacting the sexton, municipal cemetery office or local libraries or historical societies. Funeral homes and mortuaries in the area will often have lists of cemeteries in the region that can help. FamilySearch hasn’t widely microfilmed South American cemetery records or indexes. If you have ancestors who emigrated from North America to Brazil, such as those who fled the Confederacy after the Civil War, you might find them in a collection of tombstone records compiled by Betty Antunes de Oliveira (FamilySearch film No. 1162423).

Cemetery websites have expanded to include South America, although coverage varies by country. Find a Grave has a large collection of transcriptions from Argentina and Brazil, with more modest entries for Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela. Select the country name on the South American cemeteries page to see a list of cemeteries with records.

Search records for each South American country on the BillionGraves website or through the BillionGraves Index on FamilySearch. Additionally, the Interment.net site has some tombstone transcriptions from Brazil.

Whatever you learn about your South American ancestors, you’ll discover a rich history and culture that those of us in North America too often overlook. With a little effort, your family’s history in South America can be preserved long after the Olympic flame is doused.

Tip: To see the FamilySearch Wiki’s research guides and lists of digitized records for South American countries, go to www.familysearch.org/search, click South America on the Research By Location map and select the country of interest.

Suriname, Guyana and French Guiana Genealogy

Two small countries and a dependent territory—Suriname, Guyana and French Guiana—sit on South America’s northeastern Atlantic coast. Although they’re in South America, they’re often culturally tied more closely to the Caribbean. If your ancestors hail from one of these areas, you won’t find as much on FamilySearch as for other South American countries. Visit SouthAmericaGenWeb for links to genealogy information on these countries. Meanwhile, here are some quick tips to start your research.

Suriname

The smallest country in South America, Suriname has Dutch roots, having achieved independence from the Netherlands in 1975. Dutch is the official language. FamilySearch has limited how-to information at www.familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/suriname. For more help, check out The Dutch in the Caribbean World, 1670-1870 and the blog post about that website at www.dutchgenealogy.nl/dutch-in-the-carribbean-world. You may be able to learn about Suriname ancestors from the National Archive of the Netherlands.

Guyana

The Dutch colonized this English-speaking country before it came under British control. It gained independence in 1966. Find research at FamilySearch www.familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Guyana, the Guyana/British Guyana Genealogical Society and The Root blog.

French Guiana

This dependent territory of France is listed on Kindred Trails with links to a few resources, such as a Jewish cemetery project, history and maps. You may find records at the French National Archives Overseas Section in Paris or the Library of the University of the French West Indies and Guiana in Schoelcher, Martinique.