Once you determine the specific place your Eastern European ancestors came from, you’ll need to research its location. Why is this so crucial? Your Polish, Czech or Slovak ancestors’ old parish records, civil registrations and other records are organized by locality—the village, town or city and parish where they were born, married or died. So without understanding the where, you can’t unravel the who, what, when and how of your family tree.

As you may have discovered, locating your ancestral town in Eastern Europe isn’t necessarily as easy as searching for it on Google Maps. Modern maps may not show the village at all (or not by the name you know it). Your search might turn up many places with the same name. Which of the nine (or more) Dubravas in Slovakia is your family’s town? Or might it actually be Dubravica? You’ll need to use a combination of geographical references—maps, atlases and gazetteers, both modern and historical—to research your family’s Eastern European village.

This guide, which comes from my book The Family Tree Polish, Czech, and Slovak Genealogy Guide (Family Tree Books), will give you resources for tracking down your ancestor’s hometown and finding it in today’s Eastern Europe.

Poland

Poland is notorious for its difficult-to-figure-out border changes. Partitions in 1772, 1793 and 1795 saw Poland carved up and its land distributed to Russia, Prussia and Austria. Researchers studying ancestors in Poland between the first partition in 1772 and Polish independence in 1918 will need to first determine during which partition their ancestors were living, as this will affect records’ coverage and their location today.

Because of Poland’s turbulent history, administrative jurisdictions have changed numerous times and vary with the partition. Historically, powiaty (counties) were the basic geographic divisions; while those still exist, the government introduced województwa (literally, “voivodeships,” but commonly called provinces) in 1975. In 1999, it consolidated Poland’s 49 former województwa into 16. Parish boundaries have shifted over time, too—and they don’t follow those of political jurisdictions.

The internal administrative structure of former Polish territory was different in each partition:

In the Prussian partition, which today is western Poland, the land was divided into provinces and then by kreise (similar to US counties). Those were notably Poznan (called Posen in German and Polish), West Prussia (Prusy Zachodnie/Westpreussen), East Prussia (Prusy Wschodnie/Ostpreussen), Pomerania (Pomorze/Pommern) and Silesia (Slask/Schleisen).

The Austrian partition (parts of modern Ukraine and southeastern Poland) was divided into powiaty.

The Russian partition (parts of what are now Lithuania, Belarus and central and eastern Poland) was the largest and most populous partition. Land was divided into gubernias (provinces), then into ujezds (counties). Gubernias with large Polish populations were Loznan, Suwalki, Siedice, Warsaw, Kielce, Lublin, Radom and Plock. Many Polish speakers also lived in the western provinces of Russia.

Begin familiarizing yourself with Polish geography using the internet map of contemporary Poland and World Atlas Poland. Consider buying a modern road atlas of Poland, too; you’ll find these on Amazon and at other booksellers.

For historical maps, explore the online Archiwum Map Wojskowego Instytutu Geograficznego 1919–1939 (Map Archive of the Military Geographical Institute). And look for these two useful maps series on FamilySearch microfilm: Karte des Deutschen Reiches (Map of the German Empire), published by Reichsamt für Landesaufnahme, and Mapa Polski (Taktyczna) (Tactical Maps of Poland), published by Wojskowego Instytutu Geograficzny.

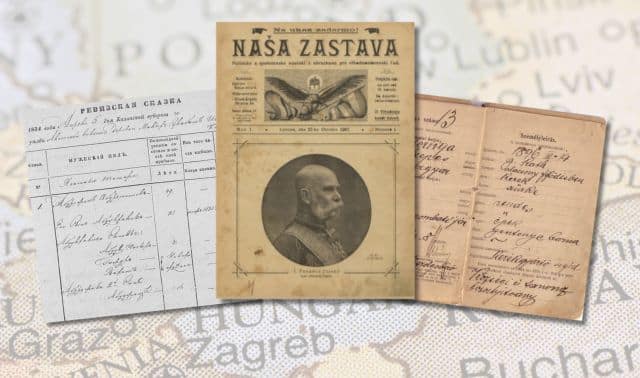

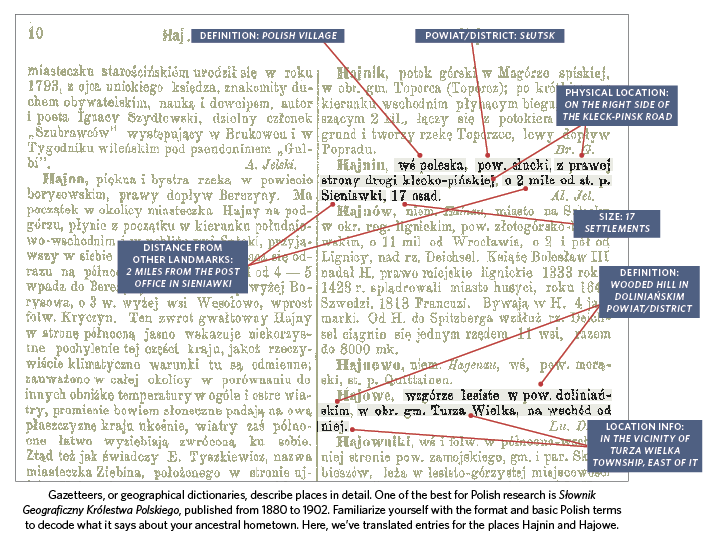

The best gazetteer for Polish genealogy is Slownik Geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego (Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland, or SGKP), a 15-volume gazetteer published between 1880 and 1902 by Filip Sulimierski. Like other gazetteers, Slownik provides a snapshot of your ancestor’s life in a Polish village, including the town’s geographic placement, information on its agriculture and trade, and historical surveys.

You can view the entire Slownik gazetteer online through the University of Poland. The website is in Polish, but if you use Google Translate, you can opt to view an English translation. The Polish Genealogical Society of America (PGSA) has translations of some of the Slownik entries and offers helpful tips for understanding entries in its members-only resource section. Consult PolishRoots’ detailed downloadable guide before diving into this digitized version.

For researching Polish places during the Second Republic (1918-1939) and later, when the country achieved independence, consult these gazetteers:

- Skorowidz Miejscowosci Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (Index to Place-Names in the Republic of Poland), published by Wydawnictwo Ksiaznicy Naukowej: This list of all localities then within Polish borders is arranged alphabetically. It covers territory now in Belarus, Lithuania and Ukraine, but doesn’t include western Polish towns that were part of Prussia in 1934. Jurisdictional information is given in columns, with churches in the final column. You can also access it on microfilm from FamilySearch.

- Spis Miejscowosci Polskiej Rzeczypospolite Ludowej (List of Place-names in the Polish People’s Republic), published by Wydawnictwa Komunikacji i Lacznosci in 1967: This work is similar in format to the 1934 gazetteer. While it doesn’t give the parish for each locality, it does provide the location of the civil registry office, which often keeps local vital records. It includes territory regained from Germany after World War II and is available on FamilySearch.

- Wykaz Urzedowych Nazw Miejscowosci i ich Czesci (List of Official Names of Places and Their Subdivisions): This online gazetteer lists modern Polish places and their associated jurisdictions in an easy-to-understand table format, with columns for nazwa miejscowosci (village name), rodzaj (type), gmina (community/sub-district), powiat (county) and województwo (province).

- Eastern Borderlands Places: You can search this online gazetteer of eastern Polish localities for a place or browse by province. It covers both governmental and church jurisdictions.

- See a complete listing of Poland gazetteers available through FamilySearch.

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic and Slovakia haven’t changed borders quite as much (or as often) as their Polish neighbors. But researching ancestral towns in these two countries, which gained independence only in 1993, still can prove difficult without the right geographical tools.

Since 2000, the Czech Republic has consisted of 13 regions (kraje) plus the capital city, Prague (Praha). Those 13 kraje encompass 76 districts (okresy); each okres is divided into municipalities (called malé okresy, “little districts”). Note that some kraje have changed boundaries over time, meaning that records from these regions might be housed in another kraje. Visit for tips on finding local records.

FamilySearch has an excellent collection of Czech maps and atlases; you’ll find them in the online catalog under the heading Czech Republic–Maps. Consider getting a modern road atlas to get cozy with Czech geography.

A helpful historical atlas, available through FamilySearch, is Militär-Landesaufnahme und Spezialkarte der österreichisch-ungarischen Monarchie (Detailed Map of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) (Das Institut). Visit Old Czech Maps to see military survey maps going back to the mid-18th century. Other websites of interest include Czech Vanished Localities and Lexicon of North Bohemian Place Names.

Aside from the possibility of multiple language variations, there’s another potential stumbling block to locating your ancestral village: Many Czech localities have similar names that can be easily confused. The FamilySearch Wiki gives an example: Kámen, Kamenec, Kamenice, Kamenicka, Kamenicky, Kamenka, Kamenná, and Kamenné are different Czech towns. Additionally, grammar rules can change place-name spellings. If your ancestors live “in Kamenka,” Czechs would say “v Kamence.” But if you want to say those ancestors come “from Kamenka,” it’s “z Kamenky.” Having a solid knowledge of counties and administrative districts can help you sort out these similar words. Compare the spellings in your ancestor’s records to historical maps and gazetteers.

Not every village in the Czech Republic had its own parish. Often, several small villages would belong to one parish. Use the following gazetteers—all of which are available on microfilm from FamilySearch—to determine the proper record-keeping jurisdiction.

- Administratives Gemeindelexikon der Cechoslovakischen Republik (Administrative Gazetteer of the Czechoslovak Republic) by Rudolf M. Rohrer (Statistischen Staatsamte): This gazetteer, published in 1927 and 1928, gives information on towns and villages in Czechoslovakia after 1918. It’s arranged by political district with an index for the entire country. Volume I covers Bohemia; volume II includes Moravia.

- Gemeindelexikon der im Reichsrate Vertretenen Königreiche und Länder (Gazetteer of the Crownlands and Territories Represented in the Imperial Council) (K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei): Based on a 1900 census, this gazetteer has a volume for each province of the Austrian Empire. Volumes are arranged by political district and subdivided into court districts, with an index to both German and local place-names at the end of the book. Volume IX covers Bohemia, volume X covers Moravia, and volume XI covers Silesia. Access digitized versions of this gazetteer at FamilySearch.org.

- Místopisný slovník Ceskoslovenské republiky (Gazetteer Dictionary of the Czechoslovak Republic) by Bretislav Chromec (Tiskem a Nákladem Ceskoslovenského Kompasu): FamilySearch bases Czech place-names in its catalog on this gazetteer, published in 1929. A second volume was published in 1935. Find a copy in a library near you on WorldCat.org.

- Ortslexikon der Böhmischen Länder, 1910–1965 (Gazetteer of the Bohemian Land, 1910–1965) by Heribert Strum (R. Oldenbourg Verlag): This resource has place-names in German, Czech and Polish for easy reference.

- Gemeindeverzeichnis für Mittel- und Ostdeutschland und die Früheren Deutschen Siedlungsgebiete im Ausland (Gazetteer of Germany and of German Settlements in Europe and the Former German Settlements Abroad) (Verlag für Standesamtswesen): This gazetteer has an alphabetical listing of settlements with a numerical code next to each place. This code refers to the specific country, county and district listed in the beginning of the book.

Slovakia

Slovakia is divided into eight kraje (regions), including the capital city, Bratislava. Slovakian kraje are divided into 79 okresy, which contain obec (municipalities) and more significantly for researchers, járás (administrative districts akin to a US county). Civil records up to 100 years old are housed in the registrars’ offices of individual járás, though accessing them requires written permission from the person’s Slovakian relative.

Localities in Slovakia have names both in Slovak and Hungarian, with many places also bearing German names. For instance, Bratislava is Pozsony in Hungarian and Pressburg in German. In the area of Subcarpathian Russia, localities also had names in Ukrainian.

Place-names are often misspelled in American sources. Difficult names may be shortened and diacritical marks omitted. And take care not to confuse jurisdictions—Slovakia has a city and a region called Trencín, for example. You’ll also encounter multiple villages with the same or similar names, too, such as Jeskova Ves and Jeskova Ves nad Nitricou (the latter meaning “Jeskova Ves on the Nitra River”). For greatest accuracy, seek as many records with the place name as possible. Double-check a town’s spelling in historical resources to trace how the name might’ve changed over time or been modified in records. Learn more about sorting out place-names here.

A current road atlas for the Slovak Republic will provide an index to current place-names and help you learn the lay of your ancestors’ homeland. The Mapy Slovakia lets you zoom in on specific areas. You also can find maps by searching the FamilySearch online catalog for Slovakia and choosing Slovakia–Maps.

When you search for old maps, remember that you’re looking for maps of Hungary or Austria-Hungary, as Slovakia didn’t exist independently in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Two good ones are the online Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia vármegyéi (Austria-Hungary 1910 County Maps) and Third Military Mapping Survey of Austria-Hungary.

The book German Towns in Slovakia & Upper Hungary: A Genealogical Gazetteer by Duncan B. Gardiner (Family Historian) was created specifically for family history researchers. If your library doesn’t have a copy, ask your librarian if you can borrow it via interlibrary loan. You also should consult Návzy Obcí na Slovensku za Ostatných Dvesto Rokov (Place-names in Slovakia During the Last Two Hundred Years) by Milan Majtán (Slovenskej Akademie Vied) on FamilySearch microfilm or in print form via interlibrary loan.

Because of Slovakia’s historical ties to Hungary, you will also be looking at Hungarian gazetteers, which are typically organized by county, district and village. The most useful Hungarian gazetteer for genealogists is Magyarország helységnévtára tekintettel a közigazgatási, népességi és hitfelekezeti viszonyokra (Gazetteer of Hungary with Administrative, Populational, and Ecclesiastical Circumstances) by János Dvorzsák (published by Havi Füzetek Kiadóhivatala). It’s known as the Dvorzsák Gazetteer for short, and it’s available on FamilySearch microfilm. Volume 1 is online through the FamilySearch Digital Library.

Here’s how the Dvorzsák Gazetteer works: Volume 1 indexes all Hungarian communities, with cross-references for variant names, by county and district. Counties are numbered at the heads of the pages. Additional names for the locality are in parentheses. Use the numbers from the index in volume 1 to find the entry for your town in volume 2, which gives specific information about the locality. The names of farmsteads, settlements and mills that belong to the locality are sometimes listed within brackets. Population figures by religion follow. For help, consult Bill Tarkulich’s excellent Dvorzsák Gazetteer tutorial. The handy Genealogical Gazetteer of the Kingdom of Hungary by Jordan Auslander (Avotaynu) is based on the Dvorzsák Gazetteer.

Research Tips:

- To access recommended FamilySearch resources here, search the FamilySearch catalog with the title or place. You also could search WorldCat to find other libraries that have the item.

- Be cautious when using Soviet Union maps (including Ukraine) between 1930 and 1990. The government falsified public maps of the country, moving rivers and streets, distorting boundaries distorted and omitting geographical features.

Related Reads

From the May/June 2016 Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: May 2025

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and affiliated websites.