1. Adopt a versatile approach when choosing research techniques.

No one or two (or even five) methods will work in any given case. The method that was brilliantly successful for one problem may slam you into a brick wall for the next. Difficult cases usually require trial and error until a clear trail emerges.

2. Learn all you can about your ancestor and his community.

Don’t focus on just a name, and look for relationships, not just straight lines. Learn his age, the name of his wife (or wives), the names and ages of all his children, the names of the children’s spouses, the names of his associates, his religion, his occupation, his economic and educational status, the exact time of his migration, and where his neighbors originated. Study county histories for the names and origins of other early pioneers in your ancestor’s community.

Isolate the first five years that your ancestor lived in the new community. Consider everyone with whom he had contact during that period as potential relatives. As people migrated, they often traveled in groups. Group members often intermarried and continued to associate with one another in the new community—particularly if they belonged to an ethnic group such as the Ulster Scots, who retained their clan system in the new country for generations.

3. Expect your ancestor to be normal.

Normal is defined here as doing what most people do at a given period of their lives. Expect him to move with others. Expect him to be married to one wife at a time. Expect him to have come from a place similar to his new place of residence.

Assume that he will form connections with other people, try to support his family, shoulder family responsibilities, strive to improve his conditions, and behave as others in his age group and socioeconomic bracket.

Look for the records normally created during the course of a life. The odds are good that you will find data pertaining to your ancestor. If that fails, move to more exotic possibilities such as bastardy bonds, criminal records and penitentiary archives.

4. Reconstruct your ancestor’s family within that community.

Then, think about how that family would have been configured at a different time; for example, how would they have appeared in 1840, 1830 and 1820? Avoid moving your research into eastern communities where you find the surname appearing, even if it is a rare one. Such fishing expeditions are rarely successful. You might spend years tracking people who had no relation to your ancestor.

5. Link younger settlers with older ones.

A man who appears to be 20 to 30 years old and who moved to a new community just before the census was taken will be very difficult to find 10 years earlier. A more mature man is more likely to have created records in a previous community and to appear as head of household in earlier censuses.

6. Think big as well as small.

Explore federal as well as county and state records. What federal records may have been created in a new territory? What entitlements might people have applied for?

Consider veteran’s benefits, bounty land, preemption grants, territorial petitions, depredations claims and so forth.

People in past centuries were no more inclined to pass up benefits and opportunities than they are now.

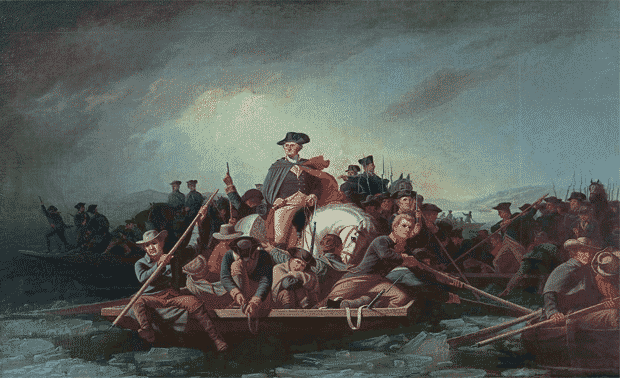

7. Search surrounding areas.

Before the Civil War, people tended to hopscotch across the west. People frequently established short-lived interim homes as they migrated across the continent. People also were as likely to move within a state as from one state to another. You can follow the trail more successfully when you understand traditional migration patterns for the period you are studying.

8. Pursue all records, since every record has potential value.

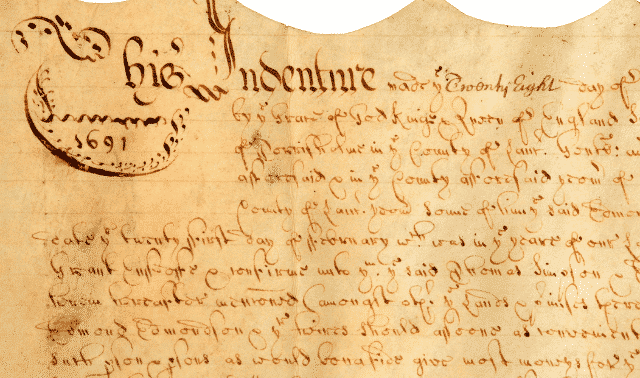

Certainly, some records are more likely to reveal significant secrets than others. But when the obvious records do not reveal the necessary connections, the researcher must turn to the harder-to-search, more obscure records that might reveal valuable nuggets of information.

9. Compare, contrast and correlate records from the old community with records from the new.

Follow the record (not just the individual and his name and search it for subtle clues rather than boldface headlines. Notice associates in your ancestor’s old community and see if they turn up in the new. And determine as accurately as possible when your family left the area where you know who they are. Try to establish connections within a period of just a few years—or preferably, just a few months—of when your family arrived or left the area where their identity is clear.

10. Identify conditions that may have motivated your ancestor to leave a community.

Consider things such as debt, an unhappy domestic life, poor or overworked soil, the inheritance of land by other siblings, or perhaps even harassment from local law enforcement officers.

11. Study history so you can determine what opportunities and land opened up within the five years prior to your family’s departure.

What Indian titles had been cleared? Were there 1812 bounty lands available? How about Oregon Donation lands?

12. Notice who stayed behind once you track down your ancestor.

Too often, our research moves when our ancestor does, so we fail to study the records created after our ancestor departed.

We must remember, however, that important documents involving that individual may continue to be generated for a long time.

These may include deeds, powers of attorney, wills, land partitions or court suits relating to the death of the individual’s parents. For example, Kindred Rose was 66 years old and had been away from his old home for 35 years when he gave power of attorney to settle his part of his father’s estate in Tennessee.

13. Don’t give up.

Tracking the origins of ancestors who lived on the frontier is fun—but it’s not easy. The work requires not only extensive study of primary records, but creativity and logic as well. But people can be found—and you can be the one to do it.