As many Americans find their thoughts drifting toward turkey and stuffing this week, genealogists are just as likely to be daydreaming about Tilley and Standish—or any of the other 24 male Mayflower passengers known to have descendants—and wondering if their ancestry holds any connections to the fabled first feast at Plymouth, Mass., in 1621.

There’s no time like Thanksgiving to inspire curiosity about possible Pilgrim roots. If your American ancestry stretches back to the 17th century, the prospects seem encouraging: Like most famous historical figures, these English voyagers’ lineages have been thoroughly traced. First, of course, you have to trace all the ancestors in between, working backward from the present.

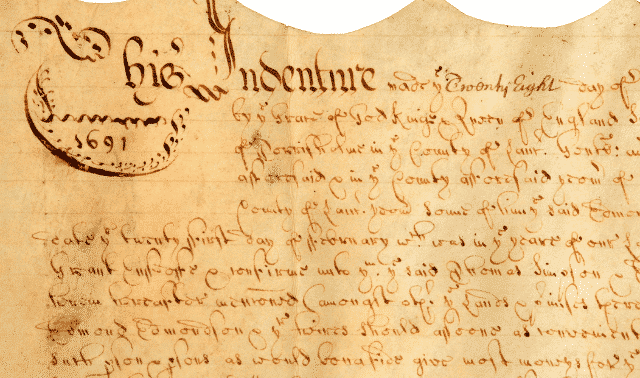

Don’t jump aboard the Mayflower too quickly, however. And don’t expect family lore to give you license to go around proclaiming your ancestors were around for the Pilgrim Thanksgiving. The General Society of Mayflower Descendants, the official group for those of Pilgrim heritage, has rigorous standards for acceptance. You can read those standards and lots more about the passengers at its website. And while one-fourth of Americans believe they’re Mayflower descendants, the society’s estimates show that fewer than half of them can be right. Read more about tracing your English ancestry in Family Tree Magazine‘s British Research Guide digital download, available from Family Tree Shop. Also see the how-to articles in our English roots heritage toolkit.

The Pilgrims aren’t your only genealogical route back to a Thanksgiving pedigree, of course. Native American roots in Plymouth lead back to the Wampanoag Indians (meaning “People of the Dawn” or “People of the First Light”). The Wampanoag Nation has a reservation in Gay Head, Mass; write 20 Black Brook Road, Aquinnah, MA 02535. And learn more about this Native American group on its website. For resources to trace all kinds of American Indian roots, see the articles in our American Indian online toolkit.