Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

As in many places, vital records form the backbone of genealogy research in Eastern Europe. Once you’ve got an immigrant ancestor’s original name and place of origin, your next step is to check for births, marriages and deaths in church and civil registration records.

But your search should not end there, especially if these records are missing or incomplete. Many archives, libraries and volunteer organizations have other genealogically rich documents—some even digitized and available online—to help fill in the gaps in your family tree. Here are 13 overlooked resources you might be missing.

Since records (including those discussed here) are typically organized by location, you’ll need to know the county or province and administrative district. Be sure to check all parishes and archives, as well as the local registrar or mayor’s office in the ancestral town or village.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll define Eastern Europe as Belarus, Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia and Ukraine. Some of the resources listed here can also help with research in other parts of the former Austro-Hungarian and German Empires.

1. Censuses

In Eastern Europe, censuses were primarily taken for tax and military-conscription purposes. When present, they can reveal name, rough place of residence, and possibly age and income.

However, your search will be “hit or miss” depending on what region you’re researching in. Because of shifting borders, record destruction, and the general chaos of war, census records may have vanished or been destroyed. Use the FamilySearch Wiki to learn what censuses survive for your ancestor’s country. Select a country, then find the link for Census under Record Types.

2. Cemeteries and Memorials

Most genealogists are already familiar with Find a Grave and BillionGraves, which can help you locate and view photos of graves worldwide. But other websites can help you specifically with Eastern European ancestors:

- JewishGen hosts a variety of databases that can help you find ancestral towns and graves: the Online Worldwide Burial Registry (JOWBR), the Holocaust Database, and the Memorial Plaques Database. (The site also has useful resources for learning about ancestral towns, whether or not your ancestor was Jewish.)

- The site Finding Lost Russian and Ukrainian Family includes a list of free cemetery databases that include residents of the former USSR. Listings cover those who emigrated to other countries as well as Russian Imperial and Soviet armies.

- Austria-based GenTeam has a searchable collection of more than 12,000 memorial cards of soldiers who died in both World Wars, many from Eastern Europe. You will need to register for an account to access the databases.

3. Court Records

Depending on time period, you may find local civil court records pertaining to contracts, marriages, inheritance, and property disputes. These can reveal names; birth, marriage and death information; relationships; place of residence; and sometimes place of origin.

Find them in local city and state archives. Or go to FamilySearch and browse the Historical Records Collections. Select Continental Europe as Place, then (under Record Type) filter for Probate & Court. At the time of writing, the site includes select records for Austria, the Czech Republic and parts of Germany.

4. Directories

Because Eastern European families tended to be large, your immigrant grandmother or great-grandfather likely left behind at least a sibling or two when they emigrated. Those siblings’ descendants could help you fill in the blanks in your family tree.

A foreign telephone directory is probably your best tool for trying to find those currently living family members. Start with Infobel or Phonebook of the World, or search for print telephone books covering your ancestral region. (Most libraries have them.)

Other, more comprehensive options include:

- The Library of Congress has some indexes and digitized versions of European address/telephone directories.

- Genealogy Indexer hosts 1.9 million digitized pages from 3,400-plus historical directories (mostly Central and Eastern European) with business, address and telephone information.

- Among its many resources for Eastern European research, PolishRoots has information on Polish city directories (click Geography & Maps). Because of language or formatting issues, you may need to consult a native-language speaker for assistance understanding them.

Central and Eastern European communities also commonly created other directories called schematisms (from the term “schematics,” referring to a schema or diagram). You will see them referred to as Schematismus in Latin; Šematism in Latinized Ruthenian from Cyrillic; and Szematyzm in Polish. Look for schematisms for diocese and other religious organizations (which often detail Roman and Greek Catholic parishes) and for government bodies (which discuss local tax or judicial officials, military outposts, and personnel).

5. Emigration Documents/Passports

Most genealogists look for passenger lists at the point of arrival. But in some instances, records might instead document departures from key European ports in Germany, England and others. Emigration lists, permissions to emigrate, and records of passports may reside in state or regional archives and include details such as the name, age, occupation, destination, and place of origin or birthplace of the emigrant.

The Slovak Genealogy Research Strategies website has examples from Austria, Hungary and the former Czechoslovakia. “Mákvirágok,” an account on the photo-sharing site Flickr, has curated a collection of passports, photos, and other documents related to immigrant lives circa 1914 to 1925.

Ancestry.com has indexes to such passenger lists from the port of Hamburg, Germany, where many European emigrants departed for the United States. Unfortunately, most passenger lists from another key port, Bremen, were either lost or destroyed. Learn about those that survived here.

The FamilySearch Library has books of emigrants from various areas of European countries, usually sorted by country/province/region. Check any listings at WorldCat, where you may find a library that offers interlibrary loan to an institution near you.

6. Land Records

While often difficult to track down, land records can go back further in time than vital records, helping you fill in generational gaps. They can also provide names of heirs, spouses, relatives and neighbors, as well as occupation and place of residence.

Various archives might hold land records today—national or regional archives, provincial archives, or town archives. Since they were created at the local level, land records weren’t kept consistently from community to community. Check with a local archivist to ensure you’re looking in the correct places.

A related set of documents, cadastral maps, were created to document the economic potential of manors. These maps of manors depicted the actual configuration of farms, complete with bodies of water, roads, etc. (often with detailed descriptions). Arcanum Maps has digitized cadastral maps, military surveys, and other maps of cities and countries. The David Rumsey Map Collection has over 120,000 map images from around the world; sort by location, date, map type, or creator.

Likewise, tax lists—though more difficult to access than land records or cadastral maps—can offer a glimpse into an ancestor’s financial and social status. Lists contain personal data on household members, and often exist for Polish communities, in particular. The Austrian Empire compiled tax records (berní rula) as early as 1653, with coverage continuing through the 18th century.

7. Military Records

In the Austrian, German, and Russian Empires, military service was mandatory for males of eligible age. In fact, conscription was often a major factor that pushed men to emigrate. That service left behind valuable documents about your male ancestors.

First, you will need to understand how conscription worked in the region your ancestor lived. Here’s some basic information about conscription in the three most prominent historical nation-states in Eastern Europe:

- Austro-Hungarian Empire: Men were eligible to be drafted at the age of 20, but could volunteer as young as 17. See a guide to these records.

- The various German states that eventually made up the German Empire had their own conscription laws. See the FamilySearch Wiki for a primer.

- In the Russian Empire, all 21-year-old males were subject to military service beginning in 1874 (although drafting of selected groups began earlier). See the FamilySearch Wiki for more.

To search surviving records, you’ll need to determine the regiment or military unit your ancestor served in. (Finding this information is not always an easy task). The types of records available—muster rolls, personnel sheets, military citations—vary by regiment and period. If successful, you could find the draftee’s birth date, religion, marital status, parents’ names, and more.

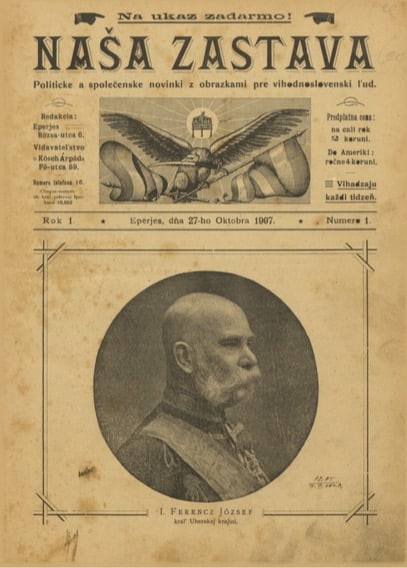

8. Newspapers and Journals

Foreign-language newspapers may contain obituaries, funeral notices, or social history background. Wikipedia has a long list of online newspaper archives by country, and you can search Google Books or the Internet Archive for relevant publications or collections. For example, search Google with related terms in each language: Towarzystwo naukowe (“scientific society” in Polish), Genealogická Společnost (“genealogical society” in Czech), or Slovenske ucene tovarisstvo (“Slovak Apprenticeship” in Slovak).

Scholarly organizations or societies (both in the United States and the home country) document the history of their region and the people who lived there, and many issue their own journals. They’re typically written in the region’s native language and may only exist in libraries overseas. Check the Periodical Source Index available on the Allen County Public Library website; click Other Countries for a Location search. The Library of Congress’ Chronicling America database has a US Newspaper Directory that lists stateside newspapers published throughout history.

9. Nobility and Seignorial Records

If you think you can prove a connection to a line of nobility, records documenting noble families may prove useful. Their contents can contain pedigrees, linkage information, personal family documents and correspondence, wills and testaments, estate records, and investigations into proof of nobility.

You can generally find such records in district or state/regional archives. Only authorized individuals may be allowed to search the records (possibly only in person), and you may also need to prove your relationship to the person in order to access documents.

Your ancestors who were among the nobility may also be in seignorial records, civil records created within a manor. Aristocrats created such records to document the life events of their lands’ inhabitants and to help administer their manors. Note that, as with other secondhand records and published genealogies, nobility records are only as accurate as the information used to create them.

10. Occupational Records

Occupational records may include guild records or other types of official paperwork. (Guilds were associations of professionals in a certain trade, such as metalworking or shoemaking.) Industry or trade directories may also be available online, or offline at libraries or local offices. GenTeam has an 1876 directory of all mills and mill-owners in Austria and a database of medical doctors from Vienna. Also check family papers for a worker passbook or work logbook.

11. Local Records, Photographs and Postcards

Collections housed in local libraries can contain “one-of-a-kind” materials: books, documents, photographs, postcards, compiled genealogies, local histories, and other ephemera. Some collections also include local government documents, such as school censuses or voting records.

Search Ancestry.com’s Card Catalog for relevant collections. Don’t rule out eBay—there’s even a genealogy category to help narrow your searches, under Others > Everything Else.

12. School Records

Records of school attendance or apprenticeship can provide additional clues about your ancestor. Documents can include school and university matriculation records, which usually provide name, age and/or birthdate, place of residence, names of the father or other relatives, and place of origin. Find them in local city and state archives. Some online collections are available at FamilySearch.

13. Town or Village Histories

Individual towns or villages may also have published histories. These sources can come in book form, or may appear on town or village websites. In addition to offering a social history of the town and its inhabitants, these publications might also mention your ancestor by name. For example, my maternal grandfather’s family is mentioned in a book, Dejiny Osturne, about Osturňa, Slovakia.

Don’t forget to search social media sites for your ancestral town. For example, a Facebook group about that town of Osturňa helped me connect with a cousin. One resident shared a tour of the houses on YouTube.

Finding Records on FamilySearch

Your first stop in Eastern European research should be the free FamilySearch, which offers a number of options to search for records.

According to Greg Nelson (who heads the site’s content strategy for East Europe), FamilySearch has been capturing images of genealogical interest in Eastern Europe since the 1960s, before the Iron Curtain came down. The first cameras were set up at the National Archives of Hungary to capture civil registration and church records. Nelson recapped FamilySearch’s recent work in the region at a RootsTech 2022 presentation.

In addition to records, key features of FamilySearch include:

- Images: Here, explore historical images not yet indexed (i.e., made searchable by name) for a locality. You can choose from selections of names from different time periods.

- Places: This landing page includes a map that shows a location along with its variant spellings. Search results will include all the database entries associated with that name and the dates any other names for that place were used.

- Research Wiki: View expert-written articles for individual countries or topics. From the main page, click the map of Europe or “List of All Localities” to navigate to your country of choice. Use the search box to type in the name of a country or topic. Either will take you to a page that includes basic information and links to other additional pages.

For more tips on using FamilySearch, see Family Tree Magazine’s article.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2022 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: March 2025