Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

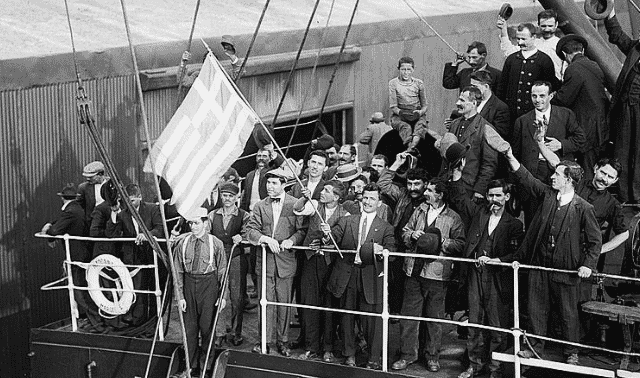

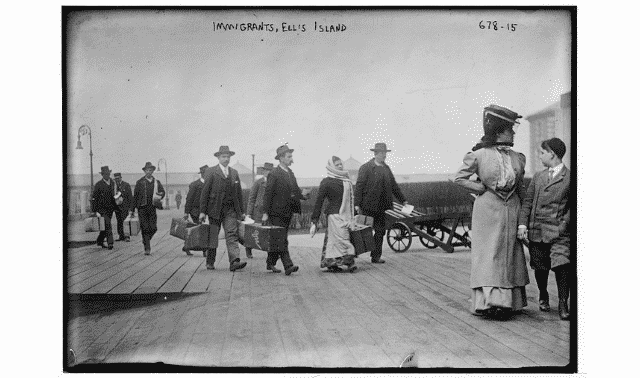

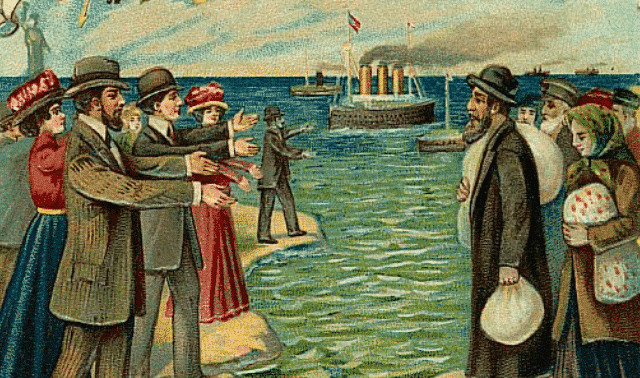

Permanently leaving one’s homeland to build a life in another country begins with hopes and dreams for a better future. Yet moving to a new land is far more than packing a valise and heading for the border. It’s a courageous, frightening, exhilarating journey to the unknown—a new place, a new language and a new way of life. For your forebears, emigration was a leap of faith, the trip of a lifetime. It involved saving funds, arranging travel to a port city and across the ocean, obtaining official permission to go (or forming an escape plan, in some cases), securing lodging and work in a strange place, and other details. We’ll share this unknown part of your ancestors’ journey and offer resources for learning more.

Push and Pull Factors

Historically, European emigration to North America has waxed and waned, reflecting changing economic, religious, historical and political circumstance on both sides of the ocean. During the Colonial era, the 1600s through the late 1700s, the number of migrants increased every year. Yet all told, fewer than a million arrived, mostly from England, Scotland, France, Germany and Holland. Not all left home on their own accord; scores were freed convicts or people who indentured themselves for years to Colonial residents in exchange for passage.

The second great wave of immigration, lasting from the early 1800s through about 1860, brought some 15 million emigrants, largely from Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Holland, Germany and the British Isles, to American shores; 800,000 also settled in Canada. From 1880 through 1920, an era of rapid urbanization and industrialization, more than 20 million arrived from Europe, the majority from Russia, Romania, Poland, Austro-Hungary, and Italy. The peak year, with well over a million arrivals, was 1907.

ADVERTISEMENT

People migrate due to a combination of forces called push-pull factors. Pull factors are positive conditions that draw people to particular destinations. These include religious and political freedom, educational and cultural opportunity, cheap land, high wages, favorable climates—the proverbial “streets paved with gold.” Push factors are negative religious, economic, environmental or political conditions that drive people from their homelands. Common push factors that spurred your ancestors’ decision to leave home include:

Religious persecution

During the 1600s, European monarchs led both church and state. Thus, Protestants were defying state authority when they sought to “purify” the Church of England of the remaining elements of Catholicism. As a result, many were imprisoned, harshly punished, and even threatened with “extirpation from the earth.” Starting in 1620, more than 20,000 of these Puritans established colonies along the coast of New England. English Quakers, German Mennonites, French Huguenots, Spanish Jews and members of other sects also sought religious freedom in the Colonies.

From 1881 through 1884, the assassination of Russian tsar Alexander II unleashed a suppression of civil liberties that included violent antisemitic riots, called pogroms, across Ukraine. The accompanying May Laws restricted Jewish settlement to designated areas and forbade issuing deeds to Jews; additional legislation limited Jewish attendance at colleges, prohibited participation in elections and more.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1903, even bloodier violence erupted in Kishinev, the capital of Bessarabia (today’s Moldova). For three days, rioters destroyed hundreds of Jewish homes and businesses and beat, raped and killed scores. In 1905 and 1906, hundreds of pogroms swept through Jewish communities in cities and villages. By 1920, more than 2 million had fled, most to the United States, Canada and Argentina.

Natural disasters

Emigration-spurring natural disasters include earthquakes, storms, floods, famine and epidemics. Potato blight led to the Great Famine that struck Ireland between 1845 and 1852. This fungal disease caused this crop—a dietary staple for Ireland’s large, desperately poor lower class—to rot in the fields. Widespread starvation, malnutrition and disease left more than a million dead; 1.5 million Irish sought refuge in Great Britain, Australia and North America.

Southern Italy, which straddles the Eurasian and African geological plates, is the only volcanically active area in mainland Europe. Eruptions have occurred periodically since ancient times, and those in the early 1900s proved particularly deadly. When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 1906, for example, more than a hundred people were killed and Naples was devastated. Two years later, a powerful earthquake struck the strait separating Sicily from the Italian mainland. It nearly leveled Messina and other coastal cities, killing up to 200,000. The quake generated an enormous tsunami. During this terrifying era, some 4 million Italians left for metropolitan areas like Massachusetts, New York and New Jersey.

Military conscription

Many European countries enacted conscription to build their armies, including France during the Napoleonic Wars, Prussia, and the Russian Empire. Tsar Nicholas I in the early 1800s required “cantonists” (students in military schools) to serve for 25 years in the Russian Army (children of nobility, senior officers and clergy had reduced obligations). Communities were expected to fulfill conscription quotas; for Jews, the lower age limit was 12. Conscripts were pressured to abandon their religious practices in favor of Orthodox Christianity. As sons neared adulthood, many parents, rather than falsify records or chop off the boys’ fingers to render them unfit, urged them to emigrate.

In the 1870s, when the Russian government weighed abolishing special military exemptions, the pacifist Mennonite community was also threatened with conscription. Though Mennonites’ appeals were initially denied, the authorities, fearing loss of such industrious farmers, offered national service as an alternative. Still, many thousands emigrated to the American Midwest and Manitoba, Canada.

Economic hardship

Lack of available land for farming, aggravated by a rise in population, caused widespread land shortages in Scandinavia and the Austrian Empire. There, a father’s land was traditionally distributed equally to his sons, leading eventually to parcels too small to sustain a family. Industrialization caused the decline of cottage industries, such as Germany’s linen weavers, who worked on home looms. Between 1880 and 1940, 4 to 5 million people left Austria, about 7 to 8 percent of the population.

War

In addition to casualties, war leads to widespread material damage, shortages of food and goods, and psychological distress. The “Spring of Nations”—revolutions that swept Europe in 1848—spurred Germans, Czechs, Hungarians and others to leave, including 30,000 Germans to Cincinnati. The Russian Revolution of 1905 saw waves of strife, strikes and military mutinies. Then at the height of World War I, the 1917 February Revolution toppled the Russian Empire, forcing the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. Eight months later, Bolsheviks replaced the short-lived provisional government with their own. By the end of the Russian Civil War in 1922, some 2 million former czarist aristocrats, intellectuals, professionals, landowners and military personnel had escaped to the United States. Others settled in Germany, France and China.

Expulsion and displacement—in effect, forced emigration—are also consequences of war. During World War II, for example, the Nazi regime expelled millions of Poles from German-occupied areas, and the Soviet Union expelled German citizens and ethnic Germans. As the German army advanced, the Soviet government evacuated an estimated 16 million people to safety across Central Asia.

Multiple catastrophes, cascading one after another, accelerate emigration. Through the 1860s, Sweden and Finland suffered a succession of poor harvests and a growing shortage of arable farmland, a situation compounded by overpopulation. Excessive rains in 1866 left potatoes and root vegetables rotting in the ground. Drought followed, then unusually long winters that shortened the growing seasons. During these “great hunger” years, urban jobs were scarce. Between 1861 and 1881, 150,000 Swedes migrated to the United States.

Links in a chain

Emigration encouraged more emigration. Recent arrivals, as they adapted to their new homeland, wrote home encouraging friends to join in benefiting from the cheap land, high wages and/or religious freedom. Their letters served as a “pull” factor, firing the imaginations of those left behind. Husbands often sailed alone, ahead of their families. On securing employment and accommodation, they financed trips for wives, children, brothers and cousins, arranging pre-paid tickets through immigrant banks. This is why you’ll see “chain migrations” of family members and neighbors following each other across the ocean and settling in the same American neighborhoods. But remember that 30 to 40 percent of European immigrants returned to their homelands, either permanently or temporarily before another trip to the United States.

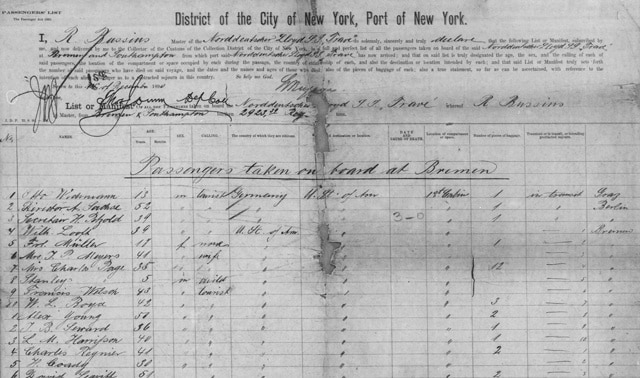

As immigration rose, the shipping trade become increasingly competitive, with nearly fifty companies battling for business. By some accounts, steerage fares for a direct transatlantic trip, which cost about $20 in 1875 (roughly two or three weeks’ wages for a laborer), fell as low as $10.

Networks of agents, linked with American employers and steamship companies like the Hamburg-America and White Star lines, plied villages across Europe with promotional posters, and guides describing the countless opportunities awaiting emigrants. They also issued tickets, some complete with travel instructions. Many emigrants purchased all-in-one, Europe-to-America rail and steamship packages. Others purchased tickets for the first leg of their trip, expecting to work en route to pay the rest of their passage.

Leaving the Homeland

Once emigrants bid friends and family farewell, they headed overland by coach, cart or on foot toward the nearest seaport on the Atlantic Ocean. Depending on the starting point, this might take weeks. Most, having worked for years to finance the voyage, left with little more than what they were wearing.

In the 1830s, when local railway companies began running trains directly to Bremen, Germany, at reduced prices, the port became a major transatlantic hub. Most emigrants booked passage in steerage, the cheapest class of overseas travel. Though conditions varied from ship to ship, these open cargo areas located on the lowest decks, were dark and damp. Passengers, crammed amid packages and narrow bunks, slept, socialized and cooked communally. Bouts of seasickness were common, especially in stormy weather as the ships pitched to and fro. Water was usually rationed and sanitary facilities were inadequate, leading to foul smells and filth that contributed to the spread of cholera and typhus. Passengers rarely received medical care, nor were they allowed access to upper decks for fresh air. These arduous trips lasted from one to three months.

As steam power replaced sails in the next decade, transatlantic ships became larger, safer and faster. Overseas trips now took about 14 days. By the 1850s, Hamburg, Germany, on the North Sea, had eclipsed Bremen as Europe’s main emigrant port. Emigration further increased as improving river routes and the development of canals eased access to ports like Antwerp and Rotterdam, Netherlands.

By the 1880s, emigrants from Eastern and Northern Europe typically made their way to large cities like Minsk,Russia; Vilna (now in Lithuania) or Vitebsk (now in Belarus); then boarded trains to ports in Bremen; Hamburg; Rotterdam, Netherlands; Liverpool, England; or Le Havre, France. Those lacking permits to travel from one country to the next might slip across river or forest borders or bribe guards to smuggle them through. Conditions on some of the newer vessels improved around this time. Families and adults traveling alone were lodged either in third-class cabins or in separate sleeping quarters. Sanitary facilities, some equipped with towels, soap and wash basins, were separate as well. Dining areas offered food in abundance. Passengers were allowed access to upper decks. They also received medical care, if necessary, on these direct transatlantic routes.

When emigrants finally reached their departure ports, they typically stocked up on food and arranged lodging for the wait until their ships sailed. During an 1892 cholera epidemic in Hamburg, shipping lines set up control stations along the German border. In addition to functioning as quarantine agents, their officials promoted German maritime interests. Travelers holding pre-paid tickets invalid for German-licensed shipping companies were denied entry, even if they were bound for ports beyond German borders. So were those holding worthless paper, palmed on them by deceitful agents. Moreover, passengers holding tickets prepaid through immigrant banks, arranged by relatives already in America, sometimes discovered that their payments weren’t recognized.

Transmigrants: Moving Through Multiple Countries

Starting about 1836, millions of transmigrants followed safer and less expensive indirect routes through Great Britain. After disembarking at British east coast ports along the North Sea—including Newcastle, Grimsby, Leith and especially, Hull—they crossed the country by train. Finally, at west coast ports like Glasgow, Scotland; or Liverpool, England, they boarded great ocean liners for the trip across the sea. These journeys could be lengthy and complex.

Typical transmigrants from the region around the Baltic Sea started by train from home to a local departure port like Malmö, Sweden; or Riga or Libau (now Liepaja) in what’s now Latvia. There, they boarded small commercial ships for Bremen or Hamburg. These trips through the Baltic Sea and around Denmark could be lengthy, costly and unpleasant. Passengers sometimes shared quarters with cattle. Some disembarked along the way in northeast Germany and traveled overland by rail to a port along the North Sea, such as Bremen or Hamburg, Germany; Antwerp, Belgium; or Rotterdam, Netherlands, where they caught another ship to the east coast of Britain. Millions of Central Europeans, on reaching Bremen, Hamburg, Antwerp or Rotterdam by rail, also boarded steamers for the British east coast.

Transmigrants could arrange complete trips in advance, for instance, a Wilson Line steamship ticket to Hull, a train ticket to Liverpool, and an Inman Line steamship ticket to New York. Passenger arrival list entries that note double-departure ports, such as Grimsby/Liverpool or Hamburg/Southampton, may indicate transmigrant journeys.

The bustling port of Hull hosted more than 2 million transmigrants, most en route to the United States and Canada. Initially, arrivals stayed on ship until their cross-country trains were ready to leave, then carried their belongings to the railway station. In 1866, however, as their numbers swelled and European ports suffered cholera outbreaks, railway companies began transporting passengers directly to private loading areas. This minimized the risk of spreading disease to the locals. It also protected the migrants, many of whom knew no English except the word “America,” from falling victim to cads hawking tickets to fictitious places, exchanging money at inflated rates, or fleecing them of their worldly goods.

In this protected area, passengers could wash up, purchase items needed for the journey, safeguard their baggage and if necessary, arrange the continuation of their journey. Hull arrivals then boarded third-class, steam-powered trains. For those who’d never ventured beyond their villages, crossing England by train was a novel experience. Though these cross-country trips might take anywhere from a few hours to a day, and the jam-packed carriages lacked toilet facilities, many passengers enjoyed themselves. Scores who were travel-weary or too poor to pay the full fare disembarked as the trains skirted Leeds, Manchester or Sheffield. Some eventually worked their way west; some remained in Britain.

Liverpool, with its established transatlantic routes and central location, had long been Europe’s foremost departure port. From the late 19th century on, though, the growing numbers of Southern and Eastern European emigrants sailed from nearer, more-accessible ports like Hamburg; Marseille, France; and Naples, Genoa and Trieste, Italy. By the early 1900s, Southampton had taken over as Britain’s main departure point for immigrants to North America.

Decreases in Immigration to the United States

In 1921, Congress passed the US Emergency Quota Act restricting annual immigration from each country to 3 percent of the US population from that place, based on the 1910 census. Immigration from southern and Eastern Europe, as well as nonEuropean countries, sharply decreased. The Immigration Act of 1924 further limited arrivals from any country to 2 percent, based on the 1890 census (these quotas were repealed by the 1965 Hart-Cellar Act). Despite the rise of Nazi Germany in the 1930s and the massive displacement of World War II, the great immigration era had ended.

Ports of call: European migrants typically started their journeys by traveling overland to the nearest port (major ones are shown here). Then he might sail directly to America or make several stops and transfers on a multi-leg trip.

A version of this article originally appeared in the September 2017 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT