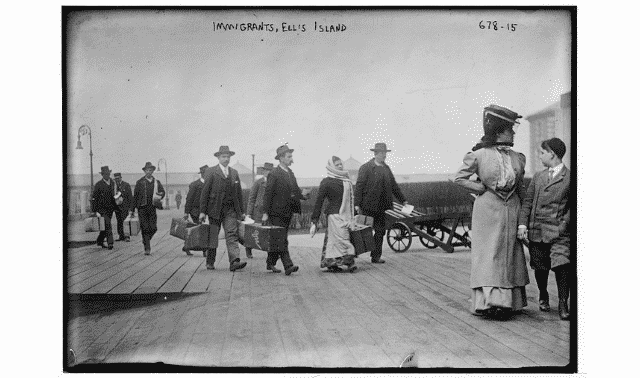

How did your immigrant ancestors get here? They came on vessels and steamships that sailed to various North American destinations: Baltimore, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, or any of the other 90-plus US ports.

Records of your ancestors’ journey across the ocean are commonly referred to as passenger lists or ship’s lists. This workbook will show what information you’ll find in passenger arrival lists, how to find them, where to find immigration information when passenger lists aren’t panning out, and tips for plucking your ancestor out of a sea of other immigrants in online databases and microfilmed records. We’ll also provide a chance to practice your passenger-list skills and a worksheet you can use to track your findings and search results.

Clues in passenger lists

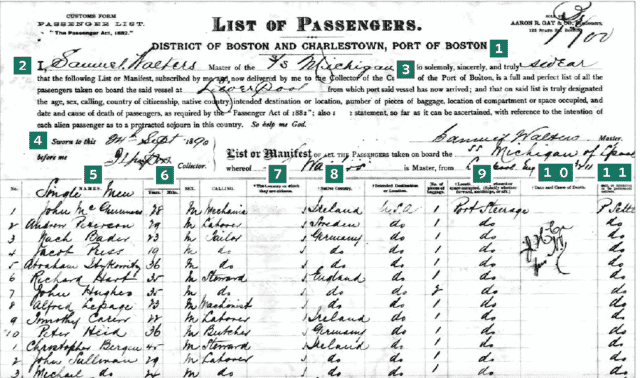

Two types of passenger lists exist, depending on when the list was created, and it’s helpful for genealogists to understand the distinctions.

Customs lists (1820 to about 1891): Starting in 1820, the federal government required all US-bound ships to keep lists of their passengers. Blank customs lists were usually printed in the United States and filled out at the port of departure by the shipping company personnel. Because their purpose was primarily statistical, these lists don’t hold extensive details—generally just the following:

- name of the ship

- ship’s master

- port of embarkation

- date and port of arrival

- each passenger’s name, sex, age, occupation and nationality

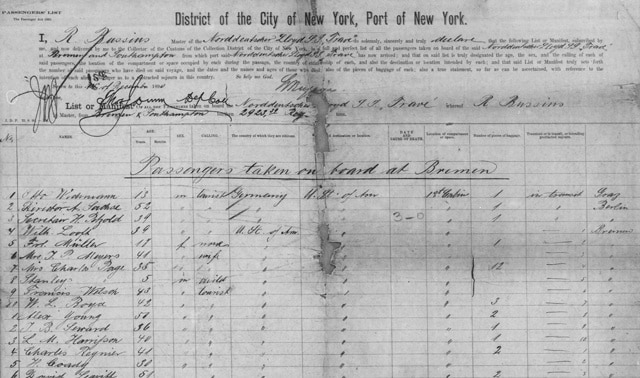

Immigration passenger lists (1891 to 1954): Like customs lists, immigration passenger lists were printed in the United States and completed at ports of departure as passengers purchased their tickets. A ship’s captain would file the list at the US port once the ship docked. The information recorded on immigration passenger lists became more detailed over time. In addition to the information on customs lists, you may find these passenger details:

- marital status

- nationality

- occupation

- ability to read and write

- amount of money in the person’s possession

- who paid for the person’s passage

- last place of residence (or whether the person is a US citizen returning from travel abroad)

- final destination in the United States

- a US relative’s name and address

- the name and address of a relative in the native country

- health conditions or handicaps

- height, weight, complexion, hair and eye color, and other identifying marks

- place of birth

You can get more specifics on what information was recorded on customs lists and passenger lists by time period using Family Tree Magazine’s free downloadable passenger list recording forms.

Understanding the patterns of immigration can help you theorize when and why your ancestors migrated. Immigrants from various cultural groups tended to arrive on America’s shores in waves, so your ancestors were likely part of a larger migration of their countrymen. Why did they leave and what drew them to a particular US locale? Sociologists and historians refer to “push” and “pull” migration factors. Push factors are conditions and events that drive people to leave their homelands, such as famines, crop failures, epidemics, high taxes, military conscription, political and/or religious persecution, war and land scarcity.

Pull factors attract people to a new area, typically providing the potential for the social and material betterment of the individual. These include jobs, plentiful land, family and other countrymen in the area, the prospect of political and religious tolerance, and US immigration policies.

Study social history to learn about migration patterns of your family’s ethnicities. For example, immigrants from their country during a given period might have originated largely from certain regions due to push factors there. And those folks might be concentrated in certain parts of the United States because of pull factors in those areas.

When looking for immigration records, keep in mind that many immigrants planned to earn money in America and then return home. Some traveled between home and the United States several times before finally settling here. A husband might have arrived years before sending for his wife and children.

Locating passenger arrival records

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is the custodian of extant passenger arrival lists after 1820. It has them on microfilm, organized by port, date and ship name. Copies are on microfilm at the Family History Library (FHL).

It’s often easier, though, to find immigration records in online databases at sites such as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org. For example, maybe your ancestor arrived sometime between 1880 and 1885, possibly in New York. You’d be in for a long microfilm search, but website search functions help you account for uncertain information. Before searching for passenger records, though, you should have a good idea of your ancestor’s original name. Because passenger lists were created at ports of departure, you’ll need to search on the name an immigrant used in the old country. This might not be the name he used in America, if he changed his name to assimilate. Contrary to popular lore, officials at Ellis Island and elsewhere didn’t change passengers’ names. They simply confirmed what shipping company personnel had already recorded on passenger lists.

Census, church, naturalization and passport records are good sources of this information, as are obituaries and family papers. Note that your ancestor’s passenger list may give his name, age and other details differently from what you might expect. Passengers may have fibbed when purchasing their tickets or the ticket agent may have incorrectly recorded information. To help you identify the right person, gather as much information about him as you can in US records, including:

- year of immigration

- age at immigration

- port of arrival

- country of origin

- family members or others he may have traveled with

If you don’t find your ancestor’s record at first, adjust your search one parameter at a time: Try removing the first name, using different spellings of the last name, broadening the birth or arrival year range, or changing the port of arrival. Search for women under their maiden and married names. Look for a traveling companion, such as a sibling or children.

These sites have the largest immigration collections and most-flexible searches. See the Toolkit box for other websites with passenger lists.

Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation

Some 40 percent of Americans have an ancestor who arrived at Ellis Island, the nation’s busiest immigration port, between 1892 and 1954. You can search digitized Ellis Island passenger lists from 1892 to 1924 (when quota laws began restricting immigration) for free. The database covers more than 22 million passengers and crew, including an estimated 17 million immigrants.

You’ll first need to register for a free account. There’s a search box on the main Passenger Search page, but finding your ancestor in this massive database may require more details. Go to the “one page form” to specify gender, years of birth and arrival, town of origin, ship name and ethnicity. You must provide a last name, but you can leave any of the other fields blank—unless you use the “sounds like” last name option, which requires at least one character for the first name and five for the last name.

Experiment with other options such as exact or close matches, or “contains” (type a syllable or other letter string). For the last name, you can pick “alternate spellings,” which finds common variations of the name (such as Smith and Schmidt). Try other spellings, too.

When you click to view a result, you’re first shown a souvenir certificate; click Ship Manifest above it. You can’t download the record; instead, order copies for a fee.

CastleGarden.org

New York immigrants were processed at Castle Garden from 1855 to 1890. CastleGarden.org offers a free search of 11 million passenger names from 1820 to 1913 (they’re not limited to arrivals at Castle Garden). Click on a name in your search results to see key details from the record—often enough to identify if it’s your ancestor. This site doesn’t, however, provide images of the lists. You can use the indexed information you find to locate the record on Ancestry.com or FamilySearch.org.

Ancestry.com

The databases in this subscription site’s giant Immigration & Travel Collection cover major arrival ports in the United States and Canada, with passenger lists, naturalizations, indexes and other resources from the 1500s to the 1900s. Most notably, you can search and view NARA’s microfilmed passenger lists (that includes the New York lists searchable through EllisIsland.org and CastleGarden.org). If you know (or suspect) the arrival port, start by searching that database to avoid getting hundreds of hits from other ports. Note the date ranges of the database you’re searching: If it doesn’t cover the year your ancestor immigrated, you won’t find a record.

Ancestry.com’s databases include published indexes and transcriptions compiled from passenger lists and other immigration sources. Your search results may include an immigrant’s passenger list and the same immigrant’s entry in a book indexing that list. Review the description of each match to make sure it’s the record you want—ideally, you want the actual passenger list naming your relative.

Access the Immigration & Travel collection under the Search dropdown menu. Use search tools such as name filters and date ranges to help you catch variant spellings and misspellings. Wildcards can help, too: ? stands in for one character; * stands for zero or more. The name can start or end with a wildcard—but not both—and it must contain at least three nonwildcards.

Fill in other information you think you know. For places, start typing and then select an option from the “type-ahead” menu of choices (you can choose just a country, or a locality within that country). If you don’t know the exact birth or arrival date, type a year and choose a range of plus or minus one, two, five or 10 years. To narrow your hits, check the box to designate a year range as exact.

FamilySearch

This free site has passenger list collections from large and small ports including New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, North Carolina, New Orleans, San Francisco and others. Many of these collections are indexed and searchable; some aren’t yet indexed and must be browsed by arrival date. Results for passengers arriving at Ellis Island link you to EllisIsland.org.

To see what’s available here, click the Search > Records on the home page. Click Browse All Collections, then filter by place for United States and Collection Type to Migration & Naturalization. Click on the database you want to search. If you’re not sure of the arrival port, you can search all the FamilySearch.org databases at once, then view results only from immigration databases.

Enter as much information as you know. To enter dates and places of birth and immigration, use the links under More Options. If the search form gives an option for Residence, you can enter the person’s destination in America, or the place a returning American citizen lives. (Leave marriage fields empty; this information isn’t noted on passenger lists.) For some collections, you can use search by relationship to add a spouse, parents or other traveling companion. Once you have your search results, you can adjust your search using the options on the left. You’ll need to register for a free account to view record images.

One-Step Webpages by Steve Morse

For more-flexible searching of immigration data hosted at EllisIsland.org, CastleGarden.org and Ancestry.com, use the free One-Step search forms at stevemorse.org. The forms let you do “sounds like” searches on first and last names, as well as the passenger’s town of origin. These are especially helpful for Eastern European immigrants. Click the form for the port you want to search (the Ellis Island “gold” form is recommended over the white). Results link you to record images on the hosting site, where you’ll need a membership to view them.

Passenger list substitutes

If you can’t find your ancestor’s passenger list—or he arrived before lists began in 1820—other records can provide some of the information you want:

Emigration records: Some European ports and countries kept track of who was leaving. Hamburg and Bremen, Germany, were popular departure ports starting in the 1880s. Unfortunately, most of Bremen’s records were destroyed. Transcriptions of the few surviving ones, dating largely from 1907-1908, 1913-1914 and 1920-1939, are online at passengerlists.de. You can search Hamburg departures (Passagierlisten) from 1850 to 1934 on Ancestry.com. The index covers only 1885 to 1914. If your ancestor’s departure falls outside those years, either browse the lists by year or use the digitized Handwritten Indexes (1855-1934).

The FHL has Hamburg passenger lists on microfilm (Auswandererlisten 1850-1934). Check both “indirect” (the ship stopped at another port en route to its destination) and “direct” (no stops) lists. The FHL has some microfilmed emigration records from other areas, including Scandinavia and the ports of Antwerp, Belgium; and Rotterdam, Netherlands.

If your ancestor traveled from or through Liverpool, England, use Ancestry.com’s UK, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960, or Findmypast.com’s outbound passenger lists from 1890 to 1960.

Citizenship records: Your ancestor could have filed for naturalization in any court. Starting in 1906, the US government processed citizenship applications. Indexes and records from various courts are online at Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org and Fold3. Post-1906 documents are available through the US Citizenship and Immigration Service. Otherwise, check records of courts where your ancestor lived.

Passports: Except for brief periods, passports weren’t mandatory for international travel until 1941. Many people got them nonetheless, and the applications may provide the place of birth, and dates of immigration and naturalization. Copies are on microfilm at NARA and the FHL, and online at Ancestry.com (1795-1925) and Fold3 (1795-1905).

Published indexes: These sources compile immigration details from customs and passenger lists, newspapers, journals and other records. The most reliable source for pre-1820 immigration records is the Passenger and Immigration Lists Index of 5 million names from 1538 to 1940. Search it on Ancestry.com and in printed form at many genealogy libraries. Also look for references such as Germans to America, 1850-1897 by Ira A. Glazier and P. William Filby.

Reading passenger lists

Once you find your ancestor on a passenger list, transcribe his information onto the appropriate form. The columns on some manifests span two pages; click or scroll ahead to make sure you have everything. Also peruse the other passengers; those from the same place as your ancestor may be traveling companions. Look for handwritten notations such as the following (learn more about these and other markings at JewishGen):

- Naturalization numbers: A series of numbers on a passenger record near your ancestor’s name, possibly with a date, is a good indication he later applied for citizenship. Officials would check passenger lists to verify information the immigrant provided on his naturalization papers.

- Detainee notations: Notes on passenger lists may indicate those detained at the port of arrival for questioning, until relatives claimed them, for illness or other reasons. Beginning about 1903, manifests included supplemental sections of detainees. An X on the left side of the passenger list, before or within the name column, usually signifies a detention. Surviving detainee lists are microfilmed at the end of the corresponding ship’s list.

- USB/Born in USA: This notation indicates the passenger was a US citizen returning from travel abroad.

Documenting your ancestor’s journey to America is a task well worth the time and effort. It can be one of the most rewarding finds in your genealogical quest.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated, October 2022.