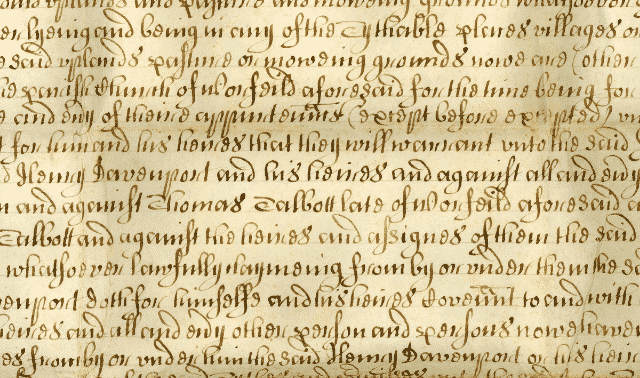

You’re apt to discover archaic terms in documents from diaries to newspapers. The meaning of the unfamiliar word may hold the clue to an ancestor’s occupation, appearance, cause of death or legal transaction.

Perhaps an old document will reveal that your ancestor worked in a zythepsary (a brew house) or was a peder (a small-tract farmer). If a letter calls your forebear a mumpsimus, he was an “incorrigible, dogmatic, old pedant,” according to Jeffrey Kacirk’s Forgotten English. That word traces back to a 15th-century preacher who miswrote the Latin sumpsimus, then refused to acknowledge his mistake. His misspelling came to signify a stubborn personality.

Unfortunately, deciphering these words isn’t as easy as cracking open the closest copy of Webster’s. When was the last time you found peder in the dictionary? Read on to learn how you can decode old, obsolete words and get on with your research.

Three Periods of the English Language

Lexicographers — people who study the history of language — divide English into three distinct periods: Old English (the fifth through 11th centuries). Middle English (the 12th through 15th centuries) and Modern English (the 16th century to the present). Within each era, new words have been born and old ones discarded in an endless cycle.

When the fourth edition of the American Heritage Dictionary was published, it included 10,000 more entries than the previous one. Words that are in vogue today, such as multitask and day trading, may not be around tomorrow. Expressions may remain in use but gain additional interpretations, or change meanings altogether.

We adopt terms from other languages and add words (such as e-mail) that come along with new technology. Even slang words that once induced parental threats of mouth washing with soap have fallen into common usage (just ask your grandkids).

You can solve word mysteries much as you do genealogy puzzles: with analytical thinking and savvy research. To decipher confounding terms, try these five tactics:

Strategy 1: Step back and spell

So you’ve come across an old-fashioned-looking word and haven’t a clue what it means. Before panic sets in, pause and look again. Write it on another sheet of paper and double-check to make sure you’ve transcribed it properly — the problem may be unclear handwriting instead of a weird word. Rather than an old term, could the word be:

- An abbreviation? Your mysterious word might just be missing some letters. For example, many legal documents contain shortened versions of common terminology. You can determine what the letters stand for by consulting special dictionaries or abbreviation keys. Compile a list of the abbreviations you encounter to save time later.

- A misspelling? Standardized spelling is a result of universal education, which didn’t happen until the 20th century. The unfamiliar word may be a spelling error. In these cases, try a phonetic pronunciation — say the word aloud and listen to yourself. It may not look like any word you know, but does it sound like one?

- Another form of English? Even though the same language is spoken in the United States. Canada and Great Britain, differences in word usage, meaning and spelling are more common than you might think. The British School of Boston even includes a short lexicon of “translations” — for example, a side-walk in America is called a pavement in England — in its weekly newsletter so American and British parents can communicate. British English A to Zed by Norman W. Schur and Eugene H. Ehrlich (Facts on File) explains the English of England. In Story of English (Penguin), Robert McCrum, William Cran and Robert MacNeil explore the language as it developed around the world. For example, depending on where your ancestor lived, he might have called a donkey a cuddy, moke, nirrup or pronkus. Locate other dictionaries through online bookstores by searching on terms such as Australian English.

- Another language? In deeds and court documents, you’ll likely encounter legal terminology in Latin. For instance, according to A to Zax by Barbara Jean Evans, habendum et tenedum means “to have and to hold” in real estate transactions. For foreign-language words, consult a translation dictionary or use a web translator such as Babel Fish.

Strategy 2: Set a date and place

A word’s meaning can change depending on when and where a document was written. Standard word usage didn’t begin until the Victorian era, when commercial, cultural and industrial factors combined with the British Empire’s worldwide expansion to create a need for a “common” language. That means the person who wrote your puzzling document may have used a newly coined word or a local dialect. Some of my Rhode Island family still uses words such as cabinet (for a milkshake) and bubbler (a water fountain). Every geographic area has similar regionalisms. To decipher them, consult a reference such as the Oxford English Dictionary, a special-subject dictionary or a historical dictionary (see strategy 5 for sources).

Strategy 3: Break it down

Separate the unfamiliar word into its parts, the same way you did in grade-school English class. Root words, prefixes and suffixes can help you discover what the word means. Its root, or stem, may be an actual word or just part of one, or a foreign word: praesto (Latin for “at hand “) and digit are roots of prestidigitation — a long way to say “sleight of hand.” Any word that starts with the prefix dis- means “in opposition to” the root (as in disagree). A word with the suffix -logy is the study of something (such as genealogy — you know that one).

For help breaking down words and decoding the parts, use the Dictionary and Finder sections in Michael Sheehan’s Word Parts Dictionary (McFarland). Word Stems by John Kennedy (SoHo Press) is also helpful.

Strategy 4: Consider context

Try using the document’s context to tease out a meaning. This works best when you understand the majority of what’s there and find only the occasional unknown word. Determine how important the word is to your interpretation of the document. The word’s meaning could be key, such as a legal term, or incidental, such as an item of clothing.

When a Spanish slave named Joseph ran away from his owner in 1765, the newspaper ad stated that he was wearing “an old light-colour’d Ratteen” and an “Oznabrigs Shirt.” Neither of those words is necessary to understand the advertisement, but Joseph’s descendants would value the details for the color and social history they add to the family story.

The context of the ad told me the words were clothing-related. Following my own advice from strategy 5, I pulled out Sally A. Queen’s Textiles for Colonial Clothing: A Workbook of Swatches and Information (Q Graphics), which features a description and swatch of the linen cloth osnabrig. And Colonial American English: A Glossary (Verbatim) defines ratteen as a “thick, woolen stuff, twilled or quilted.”

Strategy 5: Look it up

Remember how your teachers used to tell you to “go look it up in the dictionary”? When you get stuck on an archaic term, the same advice works — but the same dictionary may not. You’ll have to find the right resource. Here are a few places to begin your search:

- Websites: Online resources are helpful, especially if the mystery word was a common term or an occupation. Look in the Cyndi’s List Dictionaries and Glossaries category <www.cyndislist.com/diction.htm> for more than 80 sites, such as the Glossary of Terms Used in Past Times <www.johnowensmith.eo.uk/histdate/terms.htm>, which includes English and foreign glossaries of genealogical terms and abbreviations. If you don’t find the definition you need, ask the folks at the Old Words mailing list <www.rootsweb.com/-jfuller/gen_mail_trans.html#old-words>.

- General dictionaries: Your most important tool is the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), 2nd edition <www.oed.com>, a favorite of writers, researchers, genealogists and historians. It’s a 20-volume gold mine (most public libraries have a shorter but still invaluable version) of more than 290,000 words and 600,000-plus word forms dating to the ninth century. This is where you can find out that a gudgeon is the socket for a fire-place crane used to hang a pot for cooking. In many of its definitions, the OED provides a series of quotations from actual documents, showing how the word’s usage has changed. If you want to splurge on a dictionary for home (and cut down on your library trips — or phone calls to the reference desk), the $150 Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 5th edition (Oxford Press), is a still-thorough but more-manageable two volumes containing 500,000 words. This abridged version includes terminology back to 1700 — which covers most of the records you’d be researching. The 472,000-entry Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (Merriam-Webster) is another option at $129.

- Specialized dictionaries or reference books: Go to a library reference section and look up your word in a dictionary covering a time period or a specific topic, such as law, that’s related to your document. Also search card catalogs and bookstores for references on subjects such as textiles or tableware. Some of these books target historians and museum curators, but they’re also useful to genealogists.

- Historical dictionaries: Search a historical society’s online catalog for a dictionary printed around the time of your document. Do this as a last resort because old dictionaries can be hard to understand, and may be incomplete — until the 19th century, most dictionaries weren’t attempts to catalog all known words. The first dictionary-style lexicon, published in 1604, contained fewer than 3,000 words; 200 years later, Noah Webster’s Compendious Dictionary of the English Language listed about 40,000.

Your Own Dictionary

If you’ll be reading many documents written by a particular person or from a certain time period, make your own dictionary. Keep an alphabetical list of word problems you’ve solved, along with their meanings and citations of the resources you consulted.

Your enlarged vocabulary might open up a whole new chapter of your family history. Rather than leave you acrazed (ill or feeble), archaic words may even inspire you as they did Lewis Carroll — but if you write them into your family story, be sure to include a glossary.

Archaic Words Resources

Decipher unfamiliar words in historical documents with help from these resources.

Websites

- Bartleby.com Reference <www.bartleby.com/reference>

- History of the English Language <ebbs.english.vt.edu/hel/hel.html>

- Merriam Webster’s Inkwell to Internet <www.mw.com/about/look.htm>

- Online Dictionaries, Glossaries and Encyclopedias <stommel.tamu.edu/~baum/hyperref.html>

- Oxford English Dictionary Word of the Day <www.oed.com/cgi/ display/wotd>

- Questia <:” target=”_blank” rel=”noreferrer noopener”>www.yourdictionary.com>: Hosts an online version of the American Heritage Dictionary.

Books

- A to Zax: A Comprehensive Dictionary for Genealogists and Historians by Barbara Jean Evans (Hearthside Press)

- Ancestry’s Concise Genealogical Dictionary compiled by Maurine Harris and Glen Harris (Ancestry)

- Colonial American English: A Glossary by Richard M. Lederer (Verbatim)

- Forgotten English by Jeffrey Kacirk (Quill)

- The Language of the Civil War by John D. Wright (Oryx Press)

- The Merriam-Webster New Book of Word Histories (Merriam-Webster)

- A New Law Dictionary: Containing an Exposition of the Mere Terms of Art, and Such Obsolete Words As Occur in Old Legal, Historical and Antiquarian Writers by James Whishaw (Lawbook Exchange)

- Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford University Press): Available in several editions, including a CD-ROM, at various prices. Consult <www.oup-usa.org> or check online booksellers.

- Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang (Random House)

- Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary (Walker and Co.)

- What Did They Mean by That: A Dictionary of Historical Terms for Genealogists by Paul Drake (Heritage Books)

- The Word Museum: The Most Remarkable English Words Ever Forgotten by Jeffrey Kacirk (Touchstone)

- Word Origins: An Explanation and History of Words and Language by Wilfred Funk (Random House)

A version of this article appeared in the April 2004 issue of Family Tree Magazine.