After all, the French were among the first explorers of North America. French colonists and their Native American allies waged war on English settlers for most of the 18th century, and if the French and Indian War had gone differently, we might all be parlez-vous-ing Francais. If not for the French supplying much of the arms and munitions used by the Continental Army, our own Revolution might have gone differently. And the Louisiana Purchase from the French doubled the size of the United States.

Think about how many commonly used phrases — deja vu, carte blanche, prix fix — are of French origin. The French gave us places like St. Louis and Detroit. Even the Statue of Liberty is a French immigrant.

She’s not alone. According to the Census Bureau, more than 10 million Americans claim French roots, making it the fifth most common European ancestry. Not all of these French ancestors took traditional routes from France, but include many French Canadians in addition to those with Cajun, Acadian, Huguenot and Alsatian roots. US presidents George Washington, John Tyler, James A. Garfield and Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt all had French ancestry. Other famous Franco-Americans include Adm. Stephen Decatur, Gen. John J. Pershing (Alsatian descent), J. Pierpont Morgan, E.I. du Pont, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and even Paul Revere (Huguenot).

So how can you find out more about your own French heritage? Fortunately, the French kept excellent records. To get started, it takes only an understanding of some basic sources, a list of words that frequently appear in French documents, and these six steps:

1. Start with sources close to home.

As with all genealogical research, it’s best to start with yourself and work backwards. Don’t forget oral history and home sources such as letters, diaries and family Bibles. Clues to your ancestry may be part of your daily life, hidden in family traditions or in community celebrations such as the Mardi Gras in French-flavored New Orleans.

To be successful with your research in France, you’ll need to know the town your immigrant ancestor came from — unfortunately, nationwide indexes to vital records in France do not exist. Since you’re trying to uncover your family’s specific point of origin in France, it’s important to be methodical about your research in areas your ancestors settled after leaving France. Obviously the type of documents you use depends on the time period your ancestor arrived on this continent; there are no federal immigrant passenger arrival records before 1820, for example. For 10 tips on finding your immigrant ancestors, see the December 2000 Family Tree Magazine.

Always gather facts on your immigrant ancestor here before attempting research in French records. Don’t assume that the port of embarkation is also the town of origin — emigrants from the French countryside left through various port cities. And many groups left France with an interim stop in another country. If tracing Cajun ancestors, follow them back to their initial settlement in Atlantic Canada before making the leap to France.

2. Follow French immigration patterns.

Unlike some immigrant groups, who came largely in one or two big waves, the French arrived in many smaller ripples over a period of centuries. Some of the earliest immigrants to North America were French, and the rise and fall of French colonial power scattered them across the continent. Try to determine which category of French immigration brought your ancestors here:

• Acadians — Defined as French immigrants to Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island), these were the people immortalized by Longfellow in Evangeline. In 1755, the British forced the Acadians to leave Canada. Some Acadians went to French-controlled areas such as Louisiana, while others moved to the American colonies. The Acadian Cultural Society maintains a list of surnames for Acadian immigrants at <www.angelfire.com/ma/1755>.

• French — Some merchants and scholars traveled to the United States for business purposes and education, so it’s important to differentiate between immigrants and temporary residents. Other individuals fled to the United States at the conclusion of the French Revolution. Immigration statistics suggest that at least 50 percent of all French immigrants returned to France rather than staying in the United States. Unlike other ethnic groups that had dramatic peak years of immigration, the French arrived in this country in fairly stable numbers beginning in the 1830s.

• French Canadians — French citizens and soldiers who originally settled in the Quebec region of Canada often immigrated to industrial areas of the United States seeking work. These groups formed distinctive communities within cities in the Northeast, retaining their ethnic identity, culture and language by founding schools and community organizations.

• Cajun — Acadians who fled Canada to Louisiana became known as Cajuns. This includes seven shiploads of Acadians who escaped to Spain and were subsequently sent to Louisiana in 1785.

• Creole — Settlers in Louisiana with a mixture of French and Spanish descent or mixed European and African roots are called Creoles. They have a self-contained culture with their own patois — archaic French mixed with other languages.

• Alsatian-Lorraine — In the 19th century, immigrants from this region, historically tossed back and forth between France and Germany, settled in Louisiana and Texas.

• Huguenots — Protestant French citizens sought refuge in other countries after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 made their religion illegal in Catholic France. Even as early as 1562 some Huguenots settled in South Carolina and Florida until Spanish troops destroyed their colonies.

3. Understand naming practices.

Some confusing French naming practices can complicate your research. Prenoms or Christian names can be multiple and nicknames can be used instead of given names. Check both the birth certificates and baptismal records for name verification. Be prepared for surprises. In one Bessette family, for example, all the sisters have the same first name with different middle names; all their lives, however, they’ve been known by still other, unrecorded names — Loretta, Rita and Alice. So remember: With given names, be sure to keep good notes and never make assumptions.

French surnames follow the same rules as in other cultures, but with some additions. For example, French Canadian settlers often added an additional surname or dit name to further distinguish themselves. This means you may have to identify and search for information under several different surnames. Confused? The American French Genealogical Society offers a list of common French Canadian surnames and variations, including dit names, at <homepages.rootsweb.com/~afgs/indexi.html>. There are also cases of double surnames in families from the mountainous areas of France.

4. Tackle the challenges of reading and writing.

Before you jump to conclusions about having French ancestry because your family speaks the language, remember that’s not necessarily an indication of ancestry from France. French is spoken in some Caribbean islands, a few provinces of Belgium, the French cantons of Switzerland and in countries that were French colonies such as Algeria. The opposite is also true: Some individuals have French ancestry, but are from the non-French speaking areas of Alsace and the Basque regions.

But assuming you do have French ancestors, you’re probably thinking you only need to be familiar with French to understand records in France — well, au contraire. Records may be in Latin, German or Italian in addition to French, depending on when and where the event took place. Don’t forget that names also change when they’re translated into another language — so Jean becomes John, for instance.

Unless you’re fluent in French, you’ll need a list of words commonly found in the records to help you decipher the data and request information. The Family History Library has an excellent letter-writing guide on its site <www.familysearch.org> to help you formulate a letter, along with a list of terminology.

Online translation tools can help you bridge the language gap. Babelfish <babelfish.altavista.com> automatically translates up to 40 sentences at a time from English to French or vice versa. (For more on such services, see the Toolkit in the February 2001 issue of Family Tree Magazine.) Or try a free online French-English dictionary to translate documents yourself, such as <www.freewaresite.com/onldict/fre.html>. If you prefer to have translations done by an experienced human, try contacting a local college or university’s French department.

5. Explore French records — four basic types.

Once you get to the point of actually tapping French records, you’ll find four basic types that will help you trace your ancestry in France: vital records (church and civil), notarial documents, military papers and emigration records. The wealth of information in some of these documents will amaze you, especially if you’re unfamiliar with church documents. Others present special challenges.

• Vital records — To find French vital records — birth, marriage, death and so on — you’ll want to check not only government documents but also those of your ancestor’s church. Until 1792, only churches kept vital records. Once civil records began, church documents became less complete, but it’s still worth investigating both types of records.

Because of the importance of church records, you’ll want to try to learn not only your ancestors’ town of origin but also their religious affiliation. If you have Catholic ancestors, bone up on the various religious feast days, which is often the only way to date a baptism, marriage or death. Baptismal documents record the child’s name, parents’ names, baptism date, godparents’ names and sometimes birth date and father’s occupation. Marriages took place in the bride’s home parish, except for 1798 to 1800 when weddings took place in the canton rather than the hometown. Marriage records include the bride’s maiden name and sometimes her mother’s maiden name, too.

The Family History Library has microfilms of the records of about 60 percent of all French parishes, which you can borrow through your local Family History Center. To see if your ancestor’s parish is covered, go to <www.familysearch.org>, click on Library, Family History Library Catalog and Place Search.

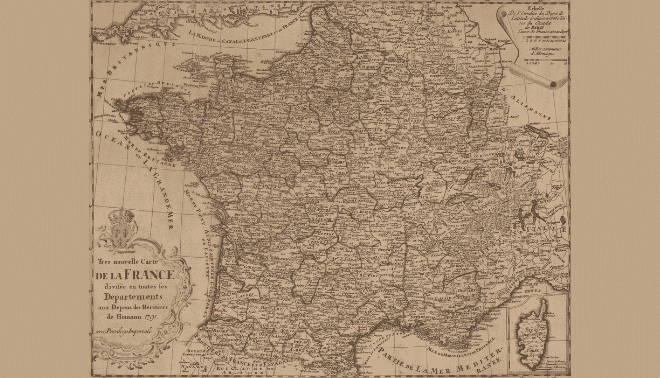

For civil records, you’ll find two sets — one in the town hall, the other in the archives of the departement. (France today is divided into 22 regions, similar to the provinces of French history; the regions are subdivided into a total of 96 departements, which date to the French Revolution. Departements are further subdivided into arrondissements, then cantons and finally communes.) The record books are arranged chronologically and usually have annual indexes.

You can request civil birth, marriage and death records from the town registrar. Only direct descendants can have access to records that are less than a century old, however. Civil authorities collected the same types of information as churches with the exception of godparents’ names.

• Notarial records — Notarial records are some of the best sources of French genealogical information, but they’re also difficult to locate unless you know the name of the notary and where he lived. These officials recorded legal events such as marriage contracts, wills, property divisions, guardianships and household inventories. Theirs are the oldest type of record kept in France.

Archived chronologically under the name of each notary, notarial documents older than 125 years are usually — but not always — located in the departmental archives. Try to determine the name of the notary in the area your ancestor lived from the departmental archives so that you can check those documents first. Families typically used the same notary for several generations, but not necessarily the one closest to them geographically.

Notarial records are mostly unindexed, though you may find lists of indexed records in local genealogical society publications. French notarial papers are only in France, so you may need to hire a professional genealogist there to assist you. Similar materials for French Canada are on microfilm, however, available through the Family History Library.

• Military records — When researching French male ancestry, place the gentleman in historical context in terms of military service. French armies participated in many long-term conflicts in Europe, as well as against the British in America. The government began keeping lists of soldiers organized by regiment and date of origin of the group in 1716. Unindexed military censuses were compiled yearly and list alphabetically the names of men 19 and 20 years old. In order to access these records, you need to hire someone to search the documents; you’ll have to provide the man’s birth year and the department that recorded his birth.

• Emigration documents — Published indexes to different types of emigration materials exist, but depend on where in France your ancestors lived, the specific group they left with and the time period. For instance, very few 19th-century passenger lists from the major port of Le Havre still exist. Whatever passenger lists still exist for France are unindexed, but usually contain the name, age, occupation, place of origin and sometimes birthplace of the emigrant.

In the absence of French emigration lists, try American records. The availability and completeness of US passenger arrival lists depends on the time period; you’ll find these in the US National Archives and in the Family History Library. In the case of French Canadians, many immigrants left family in Canada and frequently traveled back and forth to the United States. They would have left multiple entries in border crossing lists, which are also located at the National Archives.

• 6. Embrace your cultural heritage.

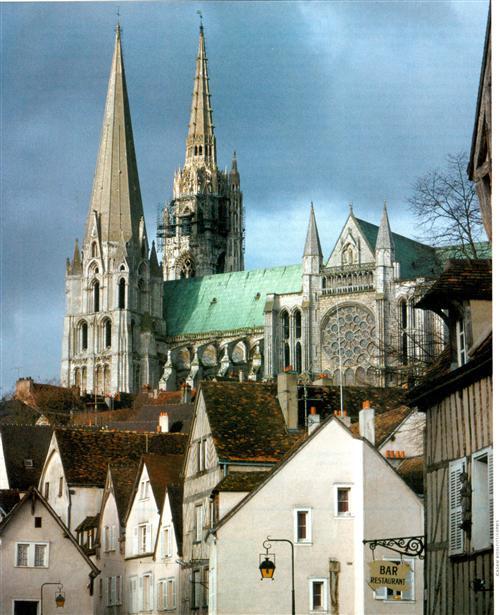

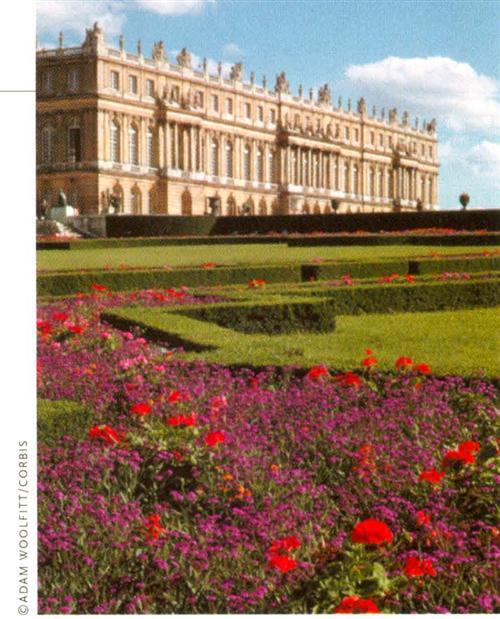

If you’re finding that the pursuit of your French roots may take you a little while, don’t worry about it. As you do your research, take time to explore French culture at every opportunity. If you live in a major city, participate in a Bastille Day (July 14) celebration. Let the charm of a French bistro in America encourage you on a frustrating day. Visit Montreal for a taste of life in a French-speaking city, or plan a trip to France itself.

It may be that your French roots are indisputable even if you never discover the original town in France your ancestors were from. My mother’s family settled in the province of Quebec, but didn’t immigrate to the United States until this century. Our French heritage is a combination of cultural traditions from France as transformed by centuries living in Canada. So far, the original town has eluded our efforts to uncover it, but ultimately it doesn’t matter — we have the French sense of joi de vivre.