Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

For years, a truism has loomed like a cloud over German genealogists: that effective research requires knowing your ancestor’s specific village of origin. But now the skies are clearing as large, searchable databases featuring German records come online. Even unindexed records previously beyond the digital grasp of researchers are now browsable on German genealogy websites, lessening reliance on archivists or volunteers.

For example, church register books—considered the “heart and soul” of German genealogy because they’re often the only 16th- to 18th-century records of commoners—are now being digitized for both Protestant and Catholic congregations. Likewise, more and more civil vital registers are coming online, as are gazetteers that can help German researchers face the challenge of changing geographic borders.

The following list represents some of the best websites for those seeking German ancestors. Note that this isn’t a ranking—each site’s usefulness will depend, to some degree, on what particular family history Sturm und Drang you may be trying to overcome. Websites that require a paid subscription are indicated with ($).

Whether your ancestors came from Berlin, Baden or Bremen, the forecast for your online German genealogy research is sunny.

1. Archion ($)

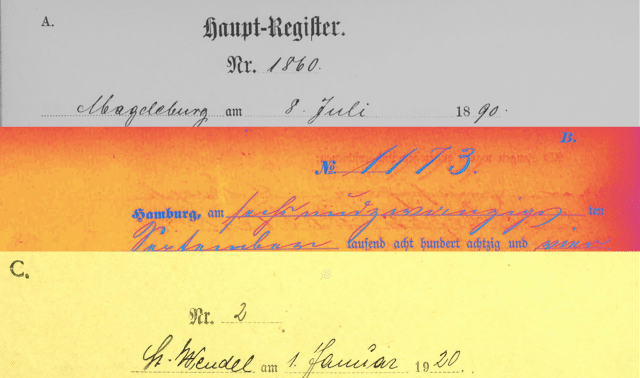

The major Protestant denomination of Germany—a loose union of more than a dozen state-based church organizations, collectively called Evangelisch—has undertaken a state-of-the-art digitization program. Since 2013, churches have added crisp scans of extant church registers on the Archion.de website, with millions of pages available as of 2020.

While Archion eventually hopes to make its scans searchable, you can currently just browse images. (So you’ll want to know the parish in which your ancestor lived before diving into Archion’s records.) In the top-right corner of the site, you’ll see a button that allows you to toggle between English and German (Deutsch) versions of the site.

A for-pay site, Archion offers a variety of subscriptions, including a one-month plan for less than 20 euros (about 22 USD). Even without a subscription, you can look at which parishes are represented on the site. In many cases, the site shows the years and types of extant records (baptisms, marriages, etc.) for a particular parish, useful so you don’t pursue documents for a parish that doesn’t have surviving records. With a subscription, you can also participate in the website’s advice forum.

2. Matricula

Accessing records for Germany’s other major Christian confession, Roman Catholicism, used to be an exercise in “downpour or drought.” Some were available on FamilySearch’s website and/or in the FamilySearch Library (see website No. 3), but many were simply off-limits.

But then lightning struck in the form of Matricula, a nonprofit organization that made its mark by digitizing Catholic Church records from the old Austro-Hungarian Empire. Among Matricula’s records, you’ll find Catholic registers from Münster and Paderborn, as well as the historically German Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. The site also has a large collection of Roman Catholic Militärkirchenbücher—the “barracks parishes” of garrisoned soldiers who were often far from home.

Like Archion, Matricula has a language “flipper” that translates the home page into English. Other pages, including those used to access original records, only appear in German. Non-German speakers will need to copy and paste text into a program such as Google Translate; Google’s “translate this page” function appears to make digital images malfunction.

3. FamilySearch

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (through its FamilySearchLibrary and website) has long provided steady “sunshine” for German genealogists. FamilySearch has enormous collections of abstracted vital records (baptisms, marriages and burials) and substitutes, as well as image-only (i.e., unindexed) original documents that users can browse.

Though FamilySearch’s light has somewhat dimmed by comparison as other online databases have come online, two of its lesser-known features also have value for German genealogists.

First is the ever-expanding FamilySearch Wiki, which has loads of articles—many authored by the expert Family History Library staffers—on geographic areas and particular types of records.

Secondly, FamilySearch Communities are a great place to request assistance with research questions or even get a record or two translated.

In addition, you can search the FamilySearch Catalog, the card catalog for the library in Salt Lake City, by entering a village name in the Keyword field to connect to all books and records relating to that town. You can also search the old International Genealogical Index, a legacy database with hundreds of millions of German church records (though it’s no longer actively updated).

4. Ancestry.com ($)

Ancestry.com has quite a number of American church records collections for ethnic German congregations, including The Historical Society of Pennsylvania collection as well as the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Church Records collection.

Other record collections, such as those of naturalizations and links to entries at Find a Grave (an Ancestry.com subsidiary) may provide the name of your ancestor’s village.

Among Ancestry.com’s German collections are the Hamburg passenger lists. Taken from that key 19th-century port, these records are broken into two collections: (1) the lists themselves and (2) images of handwritten indexes to the lists (which can be helpful when lists are hard to read and/or misindexed). Even if you already have information from your immigrant’s passenger arrival record in the United States, the Hamburg lists may include village of origin data not available in the arrival document.

For those with 18th-century immigrant German ancestry, Ancestry.com has digital versions of published resources that have entered the public domain, such as Pennsylvania German Pioneers and Naturalizations in America and the West Indies. Search these documents on Ancestry.com by given names to help account for alternate surname spellings.

Through a partnership with FamilySearch, Ancestry.com has the same collections of vital records substitutes as the free site. But Ancestry.com has better searchability for some of these loan collections, such as the Württemberg Lutheran Church records. It also has added some of the first collections of church registers from Thuringia and Saxony, the central German area that has long lacked reliable surviving records.

5. MyHeritage ($)

Internationally based subscription database MyHeritage has earned a place on this list for several reasons. The many public member trees on its site put a wind to your back by offering suggestions for researchers you can connect with. And because it has a large global focus, MyHeritage offers more potential intercontinental genealogical connections for its US users.

MyHeritage also has specialized searching technologies (Instant Discoveries and Smart Matching) that can help users build a family tree and search through others’ trees quickly.

MyHeritage also has some unique content, headlined by large collections of indexes to records from the German state of Hesse (births from 1874 to 1911, and marriages from 1849 to 1931).

MyHeritage also has a collection of church registers from the former province of West Prussia (in modern Poland) and has a strong collection of German city directories. And, like Ancestry.com, MyHeritage also loans the big German vital records substitute collections from FamilySearch.

6. Meyers Gazetteer

Though we’re not done talking about church records—no German genealogist ever is!—MeyersGaz.org hosts a valuable resource for learning about German places: a digital version of the Meyers Gazetteer. This pivotal geographical dictionary of the Second German Empire period contains a thunderous amount of information about German villages.

The gazetteer has an entry for each village, listing details such as population, whether the village had church parishes and to which civil registration, court and military districts the village belonged.

The website also shows a modern-day Google map of the area in which the village lies. A Toggle Historical Map feature lets you view a 19th-century overlay from another key German map collection, Karte des deutschen Reiches.

As part of the toggling process, both the historical and Google maps can be annotated with “pins” showing Protestant and Catholic parishes as well as sites of Jewish synagogues. In addition, you can zoom in or out of the historical and modern maps to get the perspective you need.

Best of all, this relatively new tool is also still evolving. Under the Feedback tab, users can submit comments about the site’s data or functionality. And under the E-mail tab, users can add their email addresses for other researchers who are interested in the same surnames or villages, opening up opportunities for collaboration. (The site claims the email addresses posted here are protected, so their owners will not receive spam.)

7. Kartenmeister

While MeyersGaz.org covers the entire Second German Empire from 1871 to 1918, researching later eras can be nebulous. In the “fog of war” during World Wars I and II, borders shifted and place names were changed, creating issues as you try to research ancestral hometowns.

Depending on the area, your ancestor’s village (and the records created there) may have even switched languages as land changed hands—for example from German to Polish as Poland reclaimed territories once held by Prussia and Austria after World War I.

Enter Kartenmeister, an online gazetteer. The resource homes in on villages once part of the German Empire: lands east of the Oder and Neisse Rivers in places such as East Prussia, West Prussia, Brandenburg, Posen, Pomerania and Silesia.

Kartenmeister allows you to enter a German or Polish name. The search returns information on the village that includes: other variant spellings of the place name, GPS coordinates, a link to a Google map and historical population estimates. And, like MeyersGaz, the database allows searchers to enter emails to be part of a community of interest.

8. CompGen

This free site is a Category 5 hurricane of useful tools, including databases and primers about German-speaking areas and record groups. Registration gives users some special privileges (such as participating in forums), but is not required to access the site’s databases.

Among CompGen’s features are:

- GEDBAS: millions of names in public family trees

- GOV: a village gazetteer of most of central Europe, the highlight of which is a chart showing the larger political entities to which the village has belonged

- DigiBib: a link to German’s leading library of digitized historical documents, including a large collection of Adressbücher (city directories).

You’ll also find a collection of hundreds of searchable village genealogies known as Orsfamilienbücher or Ortsippenbücher (roughly, “community genealogical history books”), or OFBs for short. Historians created these dense volumes after combing through all available extant records, creating a document that numbers each family in a community and names each individual along with vital record information.

Families are ordered alphabetically by surname, and entries give cross-references to where else family members appear in the volume. Hesse and the Hannover area are especially well represented, though the database includes OFBs from around German-speaking Europe.

The site is run by Germany’s largest family history membership organization (Verein für Computergenealogie e.V.), which focuses on online genealogy and boasts thousands of members.

You can translate some parts of the site to English. Visit the English home page. (You’ll need a program such as Google Translate for the rest.)

9. GenTeam

A considerable number of people with “German” ancestry actually have family members who hail from Austria. Given that, let’s take a look at GenTeam, a private website with millions of records and 50,000 registered users.

The brainchild of professional genealogy researcher Felix Gundacker, GenTeam is a free site that’s packed with documents—everything from the leading online gazetteer of Austrian lands to indexes of church records. (To view the latter, you’ll need to register for the site.)

10. Grimms’ Wörterbuch

Many websites give German-to-English translations, help people learn German, or decipher the old scripts used in handwritten documents. But just one hosts the Deutsches Wörterbuch, the mid-19th-century German dictionary created by the Brothers Grimm. (Yes, before they collected fairy tales, the brothers were trained as linguists.)

This dictionary—called DWB by those in the know—is the online place to find archaic words and phrases, defining them and using them in context. The dictionary is in German, so non-German speakers will need to cut and paste the text into a German translator such as Google Translate.

11. Geogen Surname Mapping

Researching uncommon German surnames? The Geogen Surname Mapping Tool identifies where the surname is found in Germany today, which may be a clue to your family’s history. Its English-language interface makes it a cinch to use.

Enter a surname to generate a perfect storm of enlightening graphics:

- a “Summary” pie chart showing an every-state percentage breakdown of where people with that surname live today

- an “Absolute Map” showing the number of people with that surname in each German district

- a “Relative Map” that shows the density of the surname in each district (i.e., how common the surname is relative to the district’s whole population

12. Das Telefonbuch

Now that you’ve identified potential relatives using Geogen, try to make contact with them using Das Telefonbuch, the electronic version of the nationwide German telephone book. The site has a simple interface: You need only enter a surname (the Wer/Was box on the site) and optionally a place name (Wo).

The search will bring back commercial and residential listings along with their associated names, phone numbers and addresses. Click an individual listing to generate a map of the person’s home address.

As in the United States, more and more Germans have only cellphones (Handys). But virtually all Germans who do have landlines will be in Das Telefonbuch—unlike in the United States, residents can only have landlines “unpublished” for specific security reasons.

Despite all the fair-weather prospects online, you’ll still face occasional whiteouts when the information you need can’t be remotely accessed. But the long-range forecast still has nothing but blue sky and—as Germans would say—schönes Wetter (nice weather).

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2020 issue of Family Tree Magazine.