Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

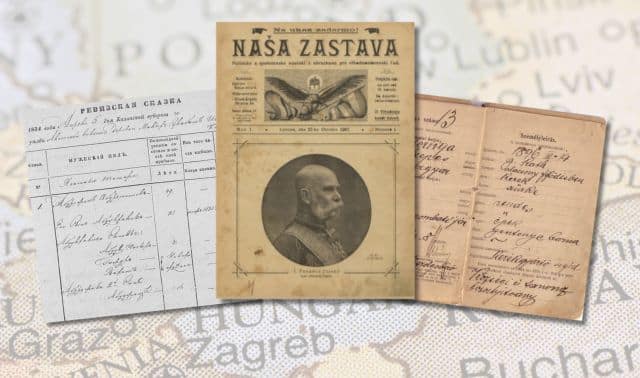

From medieval times, Germans and Russians, the largest population blocs in Europe, have seldom been allies on the world stage. And yet millions of people around the world identify in a way that seems oxymoronic: “Germans from Russia.”

A confusing designation like this seemingly happens all the time in Eastern European genealogy. “Since Great-grandpa claimed pride in being German, we always assumed the family was from Germany,” Cousin Susie, the greenhorn genealogist, says. “But now US census records claim he was born in Russia. So was he really German?”

An experienced family historian knows the answer depends on how you define “German.” The push and pull between Germanic and Slavic peoples (the latter including ethnic Russians) goes back more than a millennium. A rough German-Slavic language first developed in Eastern Europe in the High Middle Ages. And more crossover occurred in the 1700s, when Empress of Russia Catherine the Great, ethnically German herself, invited German speakers to immigrate to Russian lands.

ADVERTISEMENT

With that in mind, your “Germans from Russia” ancestors who immigrated to the United States were themselves descended from “Germans to Russia.” Let’s sort through all the history and migration patterns that led to this unique confluence of cultures. Here’s how to find your ancestors who were Germans from Russia.

How Germans Came to Russia

Following the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), the newly crowned Russian Empress Catherine the Great sought to shake Russia out of its doldrums. She opened an invitation to some Europeans colonists to found “closed cities” (areas where only colonists could live) on the Russian steppe along the Volga River, and some 30,000 German speakers took her up on the offer. Throughout the decades, settlements were founded in other parts of the Russian Empire.

Students of European history will recall that, until 1871, “Germany” was actually made up of several microstates. And many German states had been ravaged by the Seven Years’ War, making migration an attractive option for their residents. The Russian government also guaranteed colonists free land, religious freedom, and exemption from military service.

ADVERTISEMENT

But the move was difficult. Pioneers arrived on frontier land with little support or infrastructure, and the Russian government didn’t always come through on its promises to settlers.

Each settlement differed in how quickly it attracted residents, partially based on the community’s ability to obtain resources, build homes and churches, and begin farms. Only after a few generations did communities really take root in the area, with some church book records beginning as early as 1794. Settlements with prominent German populations included Bessarabia and Odesa. By the end of the 19th century, about 1.8 million German-speaking people lived in the Russian Empire, with enclaves that dotted a number of Russian territories.

The political situation eventually turned against German-Russians, with Czar Alexander II withdrawing the colonies’ special status in 1870s. Without these benefits, some residents began leaving for North and South America, often to Canada and the Upper Midwest of the United States (the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado and so on). But some settlements remained intact until World War II, when German residents were banished by the Soviet government to Kazakhstan or Siberia.

The descendants of German-speaking Russian emigrants now live all over the world, including Canada, the United States, Germany, Argentina and Brazil. Some even stayed in European Russia, Kazakhstan and Siberia.

Russian-German Groups

Each German-speaking group in Russia has its own distinct history, useful to study when exploring these ancestries. Here are some of the major groups, and when they moved to and from their towns in what was once Russia.

Volga Germans

Also known as the Volga Deutsch, this group lived in the first colonies chartered by Catherine the Great along the Volga River in the heart of European Russia. They’re arguably the most prominent of the German-Russian enclaves: the first to arrive in Russia in large numbers, the first to significantly emigrate to North America, and the longest-lasting, with many communities even enduring Soviet-era exile. Given that prominence, the Volga Germans are among the best documented; see below for more.

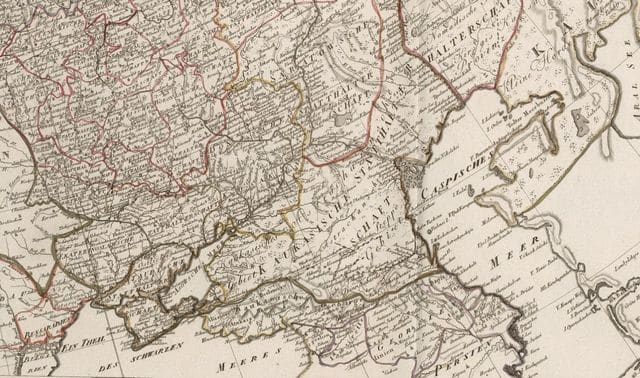

Black Sea Germans

Some isolated German settlements along the Black Sea (which borders modern Russia, Ukraine, Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria, and other countries) date to the late 1700s. They include German communities in Taurida (including modern Crimea) and Jekaterinoslaw (modern Dnipro).

But most settlements in the region are from later, during the reign of Catherine’s grandson Alexander I (ruled 1801 to 1825). In the 1770s, Russia had won land around the Black Sea from the Ottoman Empire, and Alexander extended benefits to Europeans willing to settle there.

These included:

- Odesa (in modern Ukraine), beginning in 1804

- Bessarabia (in modern Ukraine and Moldova), beginning in 1813

- Dobrudscha or Dobruja (in modern Romania and Bulgaria), beginning in 1841

Migrants moved among colonies, as well. In the 1820s, some in Odesa moved to Bessarabia and Crimea. Then in the 1840s, Bessarabia and Odesa settlers moved on to Dobrudscha.

Volhynians

The historical province of Volhynia straddles an oft-contested area near the borders of Ukraine, Belarus and Poland. Historically, it was on the border of Russia and Poland.

Some Germans inhabited this area as early as the 13th century, but a more-formal colony wasn’t established until 1783. Germans continued moving into the area over the decades, with a significant influx beginning in the 1830s.

Like other Germans-from-Russia groups, the Volhynians began emigrating in earnest beginning in the 1870s. They primarily left for Michigan and Wisconsin in the United States, as well as Canada.

Hutterites and Mennonites

Both of these religious minorities came to Russia seeking relief from persecution in the German states, which had state-established churches. The Hutterites first moved to enclave towns in 1770, and Mennonites began settlement by 1789.

Thousands of the pacifist Mennonites began leaving for the Americas in the 1870s to avoid compulsory Russian military service. The website “Odessa: A German-Russian Genealogical Library” has indexed censuses, ship lists and more for Mennonite communities.

Resources for German-Russian Research

Go-to record sets for German-Russian ancestry research vary from one group to another. Some include tax lists (kept in Russian) and various church records (kept in German or Latin).

In general, original records are still held in Russia, but difficult to obtain. Given that, you’ll want to acquaint yourself with the whole gamut of online resources. This is especially true if you lack specific information about your ancestry.

Start with the “500-pound canaries” of genealogy: FamilySearch and Ancestry.com.

FamilySearch

The FamilySearch Research Wiki has several pages dedicated to Germans from Russia and Black Sea Germans, the former of which has an overview of record types and search strategies, plus some historical context. FamilySearch’s “United States Russians to America Index, 1834–1897” identifies many 19th-century emigrants from German enclaves.

You also may want to take advantage of FamilySearch Communities, groups of volunteers who provide online help with research problems. For example, the “Russian Empire Genealogy Research” Community helps transcribe Russian documents or queries. (For assistance with entries in the German language, see the “German Genealogy Research” Community.)

FamilySearch also has German and Russian word lists, dictionaries, online gazetteers, script-deciphering how-to guides, and the FamilySearch Learning Center. Through the Family History Library, you can also set up free 20-minute online consultations with FHL staff. The library also has microfilm copies of crucial WWII Einwandererzentralstelle documents (see below), which give details on German-speaking individuals who resettled from Russia and other Eastern European areas.

Ancestry.com

Ancestry.com also brings to bear some great assets to this type of research. One example is “Kansas, U.S., Registration Affidavits of Alien Enemies, 1917–1918,” which covers a region where many Germans from Russia settled.

The site also hosts collections such at the embarkation lists from the port of Hamburg. This was often the European exit point for people leaving Russia, and these lists often contain more-precise origin information than do standard US passenger arrival manifests. In addition to the actual “Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850–1934,” there are also separate browsable handwritten indexes that can help locate hard-to-find emigrants.

Societies

Both FamilySearch and Ancestry.com hold an obituary collection curated by the Lincoln, Neb.-based American Historical Society of Germans from Russia (AHSGR). First search the collection on FamilySearch, which extends from 1899 to 2012, since it’s free.

Another society laser-focused on this ethnic group is the Germans from Russia Heritage Society, headquartered in Bismarck, N.D. That group puts Black Sea and Bessarabian Germans in the forefront, but also offers assistance for research in the Caucasus, Crimea and other Black Sea regions. Membership includes access to an Einwandererzentralstelle (EWZ) index. Both AHSGR and the Germans from Russia Heritage Society have chapters whose websites hold additional information.

Other organizations might cover Eastern Europeans more generally, but still have helpful resources for Germans from Russia. Two of these are the Foundation for East European Family History Studies and the Society for German Genealogy in Eastern Europe. The former has a large map collection, and the latter is especially strong on information about Germans from Volhynia and Russian Poland.

Another valuable resource is the mammoth database hosted by the Black Sea German Research Group. Another site offers definitive maps of settlement sites called, naturally, “Germans from Russia Settlement Locations.”

Here’s an at-a-glance list of archives and organizations that will be useful in your German-Russian research:

- American Historical Society of Germans from Russia

- Deutsch-Russische Geschichtskommission (German-Russian Historical Commission) (in German)

- Foundation for East European Family History Studies (FEEFHS)

- Germans from Russia Heritage Society

- Glückstal Colonies Research Association

- Germans from Russia Collection, Colorado State University

- Historische Forschungsverein der Deutschen aus Russland e.V (Historical Research Society of Germans from Russia) (in German)

- Society for German Genealogy in Eastern Europe (SSGGE)

- Volga German Institute at the University of North Florida

Other Websites for German-Russian Research

- Black Sea German Research

- CompGen (in German)

- Cyndi’s List: Germans from Russia

- FamilySearch Research Wiki: Germans from Russia

- GenWiki (in German)

- Germans from Russia Settlement Locations

- North Dakota State University Germans from Russia Heritage Collection

- Odessa: A German-Russian Genealogical Library

- The Volga Germans

German-Russian Genealogy Books

- A Brief History of the Germans in Russia by Igor R. Pleve, translated by Richard R. Rye (American Historical Society of Germans from Russia)

- A Century of Russian Mennonite History in America by Harley J. Stucky (Mennonite Press Inc.)

- From Catherine to Khrushchev: The Story of Russia’s Germans by Adam Giesinger (American Historical Society of Germans from Russia)

- Genealogical Guide to German Ancestors from East Germany and Eastern Europe, English edition, by Arbeitsgemeinschaft Ostdeutscher Familienforscher (Degener & Co.)

- The German Colonies on the Lower Volga by Gottieb Beratz, translated by Adam Giesinger and Leona W. Pfeifer (American Historical Society of Germans from Russia)

- Germanic Genealogy: A Guide to Worldwide Sources and Migration Patterns by Edward R. Brandt (Germanic Genealogy Society)

- Voices from the Gulag: The Oppression of the German Minority in the Soviet Union by Ulrich Merten (American Historical Society of Germans from Russia)

- Wir Wollen Deutsche Bleiben: The Story of the Volga Germans by George J. Walters (Halcyon House)

Einwanderungszentralstelle Records

One group of records, those of the Einwanderungszentralstelle (EWZ), or Central Immigration Control Department, warrants special consideration. During World War II, ethnic Germans resettling from countries in Eastern Europe back to Germany were required to fill out a number of forms with the EWZ to request naturalization as German citizens.

Records created by the EWZ can be critical for German-Russian research—perhaps functioning as the only information available about a family during the volatile WWII era. Records might even include relatives who emigrated decades earlier, since documentation sometimes includes “collateral” family members.

The EWZ collection spans more than a million individuals on 7,300-plus rolls of microfilm. Documents include:

- Application forms: These document an individual’s full name; birth information; last place of residence; names of parents, spouse and children; death dates; citizenship; religion; and even life story.

- Health cards: These list a person’s basic health and physical characteristics, plus some of their relevant family history. Cards often include a photo.

- Family trees: These may take the form of a three-generation chart.

Note that many documents haven’t been digitized, and it’s difficult to find extant copies of all three kinds of documents. Copies of application forms are on National Archives microfilm (A3342) at the College Park, Md., location. Cards and family trees are on Family History Library microfilm, but can only be accessed in person at the library.

Fortunately, applications have been indexed by various sources. The Black Sea Germans Research site has a helpful primer.

• • •

Whether they go by Volga Germans, Germans from Russia (or Bessarabia or Crimea or Odesa), or Volhynians, these caught-in-between people have left behind key records that will help you research their unique hybrid ethnicities. A stroll through the websites devoted to them will show you that, despite the confusion you might have originally encountered, you’re not alone in your quandaries—or in solving them.

A version of this article appeared in the November/December 2022 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT