Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

While Irish civil registration records aren’t perfect—they don’t contain all the genealogical information you might want them to—the collections provide building blocks for your genealogical research and help you work back in time, generation by generation.

In this excerpt from my new book The Family Tree Irish Genealogy Guide (Family Tree Books), you’ll learn how the Irish civil registration system worked and where you can access its records—especially online.

What is the Civil Registration system?

Beginning in 1845, the Irish government mandated that all marriages be recorded. But in practice, only non-Catholic marriages were recorded until full registration was enacted in 1864. From that year on, all births, marriages and deaths were recorded. See the box on the next page for more on how Irish civil registration evolved. Read more about the history of Irish civil registration here.

The new system divided Ireland into approximately 160 superintendent registrar districts (SRDs), comprising exactly the same boundaries as another administrative district known as the poor law union. Each SRD included several registration districts (also called dispensing districts), which you can identify online, each with its own registrar.

At the end of each quarter of the year, each registrar copied the details of all the births, marriages, and deaths (BMDs) he’d registered. These quarterly returns—effectively duplicates of the originals that remained in local custody—were sent to the General Register Office of Ireland (GROI) in Dublin, where they were arranged into bound volumes and indexes were compiled.

Unusually for Ireland, the civil registration collection is considered complete—in the sense that records have survived intact. Having said that, not every birth, marriage and death was recorded. Even though the system was compulsory, up to 15 percent of vital events are thought to have gone unregistered, at least in the early years.

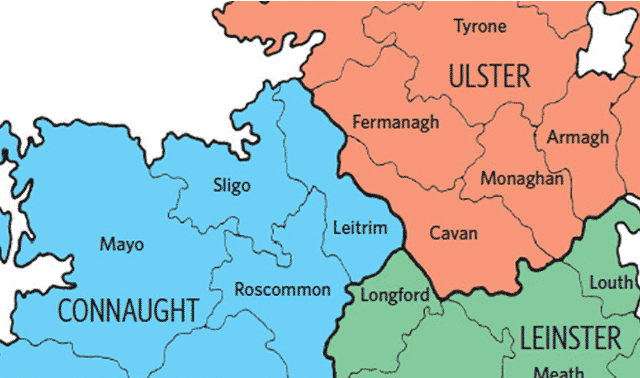

Nonregistration was particularly a problem in the more rural, western seaboard: counties Clare, Cork, Donegal, Galway, Kerry, Mayo and Sligo. In the minds of ordinary folk, this new registration system was simply redundant given that similar records were maintained by the local church parish. What need was there to give information about a birth to the authorities, when the infant’s baptism had been recorded in the church register? Baptisms were less likely to go unrecorded than were civil registrations of birth, so family historians can usually find a secondary source to support a date and place of birth for an ancestor.

What can civil records tell you?

Let’s take a look at each major record type and what you can expect to find within it:

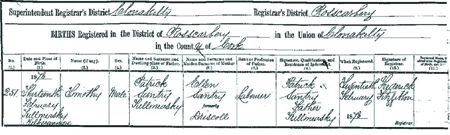

Registration of births: Birth registration began Jan. 1, 1864. The information recorded in each registration included (when known) the date and place of birth; the name and sex of the child; the father’s name and address; the mother’s name and maiden surname; the father’s profession or rank; the informant’s name, qualification, and address; the date of registration; and the registrar’s signature.

To encourage timely registrations, especially for births, a late registration penalty or fine was imposed on tardy parents. To avoid the fine, some parents would give an incorrect, later date of birth for a child. This happened with my grandfather in Clonakilty, County Cork. He celebrated his birthday Jan. 20 every year, but his birth certificate states he was born Feb. 13. Sure enough, the church register shows he was baptized on Jan. 21, nearly four weeks before his “official” birth. In fact, the law allowed 12 weeks to elapse before imposing a penalty, so there wouldn’t have been a price to pay for registering baby Timothy’s correct birth date, anyway. As he was their first child, perhaps the new parents were not aware of the long lead-time allowed.

Either parent could register the child, and a number of others were also qualified to attend the registrar and provide the information: various relatives, an occupier of the house in which the child had been born, a midwife and even neighbors. When a child was born out of wedlock, only the mother’s details were recorded unless the father also attended the registrar’s office. The register books didn’t necessarily provide the home address of a single mother; whether or not to include this was at the registrar’s discretion.

Registration of marriages: The information recorded on marriage certificates is similar to and sometimes more detailed than that on some early US marriage registrations. For each marriage, the date, place and denomination is recorded, along with both parties’ names, ages, marital statuses, occupations, home addresses, and fathers’ names and occupations. Two witnesses’ names are also noted. In practice, ages are rarely noted other than whether or not the parties were “full age,” meaning 21 or older. If one (or both) of the parties’ fathers was deceased, this was supposed to be noted but often was not. Illiteracy was noted by an X in the middle of a “signature,” usually with “his mark” or “her mark” added.

Marriage registrations in the Republic of Ireland didn’t record birth dates for the bride and groom or the names of both parents until 1956. At the same time, the father’s occupation ceased to be requested.

Overall, marriages were less likely than other kinds of vital records to be registered late, but there were some issues when Roman Catholic marriages were added to the compulsory system in 1864. While Anglican parishes and Presbyterian congregations had been issued printed registers that they had to copy and submit to Dublin every quarter, responsibility for the registration of Catholic marriages landed on the bride and groom. It apparently wasn’t a priority for most young couples, as many marriages failed to be registered in the early years. Beginning in 1880, this responsibility shifted to the parish priest.

Registration of deaths: Of the three forms of registration, deaths were most likely to fail to be registered. Missing death registrations can be especially problematic, as few Roman Catholic parishes maintained burial registers.

Death certificates are the least informative vital record, genealogically speaking. Details included were date and place of death; the name of the deceased; and the deceased’s sex, marital status, age and occupation. In addition, the record listed a cause of death and the informant’s name, qualification, and address. The registrar was required to note if the deceased’s home address was different from the place of death, but in practice this instruction was not consistently followed. (Note that Irish death registrations don’t record how and where the body was disposed.)

While official responsibility for registering a death lay with the next of kin, it was often registered by an official when a death occurred in a hospital or other institution. Given this, details should be treated with caution because information was too often guessed: Home addresses might be omitted, ages rounded up or down, occupations given simply as “laborer” even when they were more trade-specific, and marital statuses noted as “married” even if the deceased was actually widowed.

Such little information is recorded in Irish death registrations that it can often be impossible to correctly identify a relevant record for individuals with common names (John Murphy, for instance). Dates, places of birth, and parents’ names weren’t recorded until relatively recently.

How can I access civil records?

Records offices have been scrambling to improve access to vital records, once available only as hard copies or on microfilm. The result is a rather confusing muddle of availability across state-run, commercial and nonprofit sites. Some use the same data set but have made their own enhancements, such as full record transcriptions or record images. In addition, these sources’ geographical and chronological coverage varies. Yes, it really is a mess. But never mind. We’ll outline which sources you can consult and what you’ll find there.

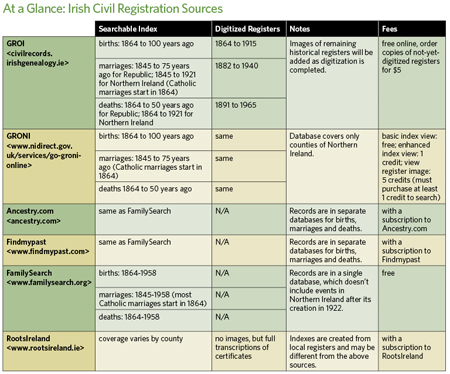

Two independent government organizations cover the island. Both provide access to records of birth up to 100 years ago, marriages to 75 years ago, and deaths to 50 years ago. In both cases the historical records start in 1864 (1845 for non-Catholic marriages). Additionally, both offices have carried out digitization of some or all of their records. Each site is independent of the other and operates differently.

General Register Office of Northern Ireland (GRONI): Following the Partition of Ireland in 1922, which established the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland (a province of the United Kingdom), the GRONI was set up in Belfast to deal with civil registration of births, marriages and deaths in Northern Ireland. This archive holds copies of all historical records from the six counties of Northern Ireland up to and including 1921, plus records created since that date. GRONI’s online database is fully digitized, and indexes are updated weekly. Each of its records has a unique reference number for easy searching and citation.

To use the site, you need to register and purchase credits (about $1 each) before you can run a search and view results. You must have at least one credit in your account at all times. Viewing basic index results won’t cost you any credits, but enhanced index results, which include a bit more detail, cost 1 credit (see what you can find in basic versus enhanced results). You can view a register image for 5 credits. If you’re looking for records outside the dates held in the database, you’ll have to order an official certificate. See GRONI’s website for instructions.

General Register Office of Ireland (GROI): Headquartered in Dublin, this office holds historical records for the entire island (all 32 counties) up to and including 1921, and for the 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland from 1922. Unlike the GRONI database, the online database created by GROI is free to access. Its digitization project is complete for birth records; search results include an image link to downloadable PDFs of the original register page.

You can also link from search results to images of marriage (1882–1940) and death (1891–1965) registers (some earlier registers also may have been digitized). Earlier registers are still being digitized. You can order a photocopy (called a research copy) of the register entry for about $5, with your choice of email or postal delivery. See the website for application forms. You can use the same application form to request a manual search of the register if you can’t identify your ancestor’s entry on the GROI database but are confident there should be one. Because the GROI site can be fussy about surname spellings and wildcards, try another database if you’re having trouble finding an entry that should be in the database.

For instructions for purchasing official certificates for births, marriages and deaths held by GROI, see the database’s help page. Official certificates have information extracted from the register; they don’t provide any more information than the digitized image or a photocopy.

FamilySearch.org, Ancestry.com, and Findmypast: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints microfilmed GROI indexes up to 1958 and made them searchable free in the FamilySearch database “Ireland Civil Registration Indexes 1845–1958.” Remember that this index doesn’t include entries for events in the six counties of Northern Ireland after 1922.

FamilySearch has since shared this database with subscription sites Ancestry.com and Findmypast, where you can search it in separate collections of births, marriages and deaths. These sophisticated websites make it easier to find variant spellings of surnames, but they don’t have images of the registers. Use the index results to view or order the records at GROI or GRONI.

RootsIreland: The Irish Family History Foundation’s island-wide network of county-based genealogy centers has been busily transcribing parish and civil registers for many years for its subscription website, which now holds more than 20 million record transcriptions. Its civil registration records are created from the locally held birth, marriage and death registers, rather than the copies sent to Dublin, making this database a unique resource and always worth checking if you can’t find a particular entry where you think it should be.

At least 15 of the county research centers have collections of civil register transcriptions. Some have the full mix of birth, marriage and death records, while others have only marriages. Search the detailed list of records in the database for each county before you decide whether to subscribe.

More Resources

Free Web Content

Historical Irish jurisdictions

How to use Griffith’s Valuation

Q&A: Finding ancestral origins in Ireland

For Plus Members

Search the 1901 and 1911 Irish censuses for free

12 best websites for Irish genealogy

Irish genealogy resources

Products

The Family Tree Irish Genealogy Guide

Video download: Irish Church Records

Irish Genealogy Cheat Sheet

ADVERTISEMENT