Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

“What’s new?” This question ranks high on the FAQ list when you run into someone you haven’t seen for a while.

In genealogy, “What’s new?” can elicit an excited iteration about a new website filled with indexes or records, making an ancestor search quicker and easier. But ask a researcher tracing Italians “What’s new?” and you’re likely to get a shoulder shrug, a toe kicking the dirt, a mumbled “Not much.”

While It seems Italian genealogy is moving into the electronic age at a sloth’s pace, a sizable number of records have popped up on sites such as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch, but I bet they aren’t the ones you need.

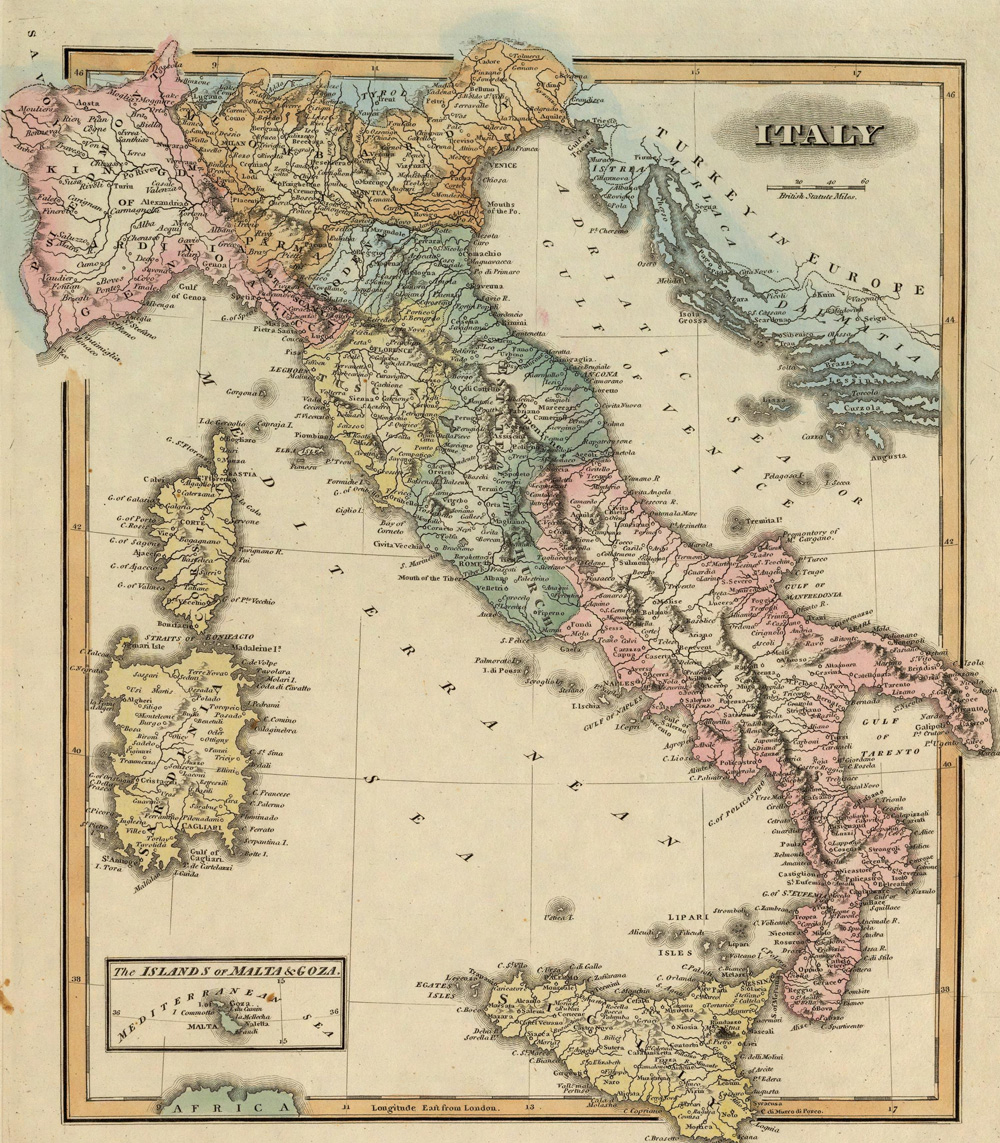

In Italy, records—births, marriages, deaths, recent censuses and church records—are kept at the local level, in town halls and churches. In its Italian research outline, the Family History Library (FHL) boasted of “about 60,000 microfilms and microfiche containing information about people who’ve lived in Italy.” While these records have now mostly been digitized, remember, the FHL doesn’t have every record on microfilm for every town and every time period. So you can see the magnitude of the problem for going to all those local repositories and getting their records digitized and online.

The news isn’t all gloom and doom, though, and this article shows you steps for digging into your Italian roots. But first, let’s focus on 10 resources that’ll enhance your research and get you going—without having to go to Italy.

1. Comuni Italiani

This website is molto bene! By clicking on one of the regions in Italy, Apulia (Puglia in Italian), say, you’ll learn the names of all the provinces. Then click on a province—I chose my ancestors’ province of Bari—to get a list of all its towns and cities. Then click on the town, in my case Terlizzi, and you’ll discover helpful genealogy links.

One link gives you a Google map of the area. You can zoom in for a detailed street map. Another link delivers you to a phone directory so you can track down potential relatives with your surname. I tried DeBartolo, but didn’t get any hits—which I thought odd, as I’ve visited DeBartolo cousins in the town. When I entered just Bartolo, however, it brought up all the DeBartolos in Terlizzi.

By clicking on the town’s official site, I could take a virtual tour of the area, or look at photos of local landmarks. And if you’re wondering who the town’s patron saint is—or the mayor—you can find that information along with the number of families who live there.

The town page on Comuni Italiani gives you the address and the phone and fax numbers for the town hall, as well as an e-mail link. Of course, you’ll need to write your letter or e-mail in Italian.

2. Social histories

You may have heard me say this before: Genealogical research gives you only half the story—the who (names), where (places) and when (dates). But social history research gives you the other half: the how, what and why. How did your ancestors live their lives? Why did they leave Italy? What was it like to be an Italian immigrant in America? Unless you’re fortunate enough to have surviving letters and diaries—or even better, the immigrant generation still alive to tell you—reading social history books can give you details that fill out the bare bones on your ancestor charts.

Italian-American life and immigration is well-explored in classic books such as La Storia: Five Centuries of the Italian American Experience by Jerre Mangione and Ben Morreale (Harper Perennial), Italian-American Folklore, by Frances M. Malpezzi and William M. Clements (August House Publishers), and Blood of My Blood: The Dilemma of the Italian-Americans by Richard Gambino (Guernica Editions).

More recent publications include oral histories, autobiographies, and memoirs of Italian-American life and culture. For example, The Italian American Reader by Bill Tonelli (Harper Paperbacks) is an anthology bearing the description “part manifesto, part Sunday dinner.” It’s a collection of excerpts from Italian-American-authored novels, memoirs, short stories, essays and poems, covering a broad spectrum of lives from little Italian grandmas to gangsters.

3. Italian newspapers

The country’s largest collection of Italian language and Italian-American newspapers and periodicals is archived at the Immigration History Research Center (IHRC) Archives at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. The IHRC Archive is open to researchers weekdays; see the website for hours. All research must be conducted in the IHRC because their materials do not circulate; off-site researchers can contact them to see what arrangements can be made.

Not many Italian papers have been digitized, but continue to check newspaper sites such as GenealogyBank. If your Italian ancestors settled in major cities such as Boston, New York or Chicago, you’re more likely to find obituaries or other news items about them in mainstream newspapers that are digitized online.

4. Order Sons and Daughters of Italy in America

According to its website, the Order Sons and Daughters of Italy in America (OSIA) was originally called Oridine Figli d’Italia. A group of Italian immigrants who came to the United States during the great Italian migration from 1880 to 1923, including Dr. Vincenzo Sellaro, established the organization in New York City’s Little Italy June 22, 1905. They wanted to create a support system that would help Italian immigrants become US citizens, assimilate to American life, and obtain health and death benefits and educational opportunities. More than 600,000 members of this still-active group belong to 650 chapters (lodges) across the country, and membership is open to men and women of Italian heritage.

The IHRC in Minneapolis is the depository for the organization’s historical membership and other records. If you think a relative was a member, visit the IHRC Archives page and type Order Sons of Italy into the Search field to learn what records the IHRC holds. But as mentioned above, if you find a promising entry, you’ll need to visit the center or contact them for off-site research possibilities.

5. Naming traditions

Learning the traditional naming pattern many Italians followed might help you identify more relatives in Italian records. Most couples stuck to the custom of naming the first son after the father’s father; the second son after the mother’s father; the third son after the father; the first daughter after the father’s mother; the second daughter after the mother’s mother; and the third daughter after the mother. If you haven’t identified your immigrant ancestor’s parents, you can make an educated guess about their given names based on this pattern.

For example, Salvatore and Angelina (Vallarelli) Ebetino named their children—listed in birth order—as follows:

1. Francesco

2. Fortunato

3. Fortunato

4. Stella

5. Isabella

6. Felice

7. Michele

8. Michele

9. Salvatore

From this, we can reasonably guess that Salvatore’s parents’ names were Francesco and Stella, the names of his first son and daughter, and that Angelina’s parents were Fortunato and Isabella, the names of her second son and daughter. My further research confirmed this was exactly the case. Notice, also, that they named two children Fortunato and two Michele. This is because the first Fortunato and the first Michele died in infancy. To preserve the naming pattern, Salvatore and Angelina used the names again for the next child born of the same sex. This type of name is known as a necronym and was common in Italian families.

To find out more about Italian names, visit Behind the Name, which gives you Italian name details such as pronunciation, origin and masculine or feminine usage. For more sites on Italian first and last names, visit Italian Names in Italy at Italian Genealogy Online. To see a distribution of your Italian surname in Italy, look at the maps on the website GENS.

6. Translation tools

Translating words from Italian genealogy records is as easy as typing them into a translation website. For just a word or two, you can use an online translation dictionary, such as Reverso. For longer phrases and sentences, try Google Translate.

If you’re writing a short records request to an Italian town hall, you can paste your letter in English and then have it translated into Italian. Remember, though, you’ll get a literal translation. For best results, compose your English version in formal language, avoiding contractions, slang and colloquialisms (otherwise, your letter might sound like one of those foreign spam e-mails asking to deposit millions of dollars into your bank account). You also can use FamilySearch’s Italian letter-writing guide to compose your request. It also tells you how much money to send and in what currency, and where to mail your request.

Historical records can be more tricky to translate because of the dialects and archaic language. To help you translate civil registration birth, marriage and death records that you’ve found on microfilm from the Family History Library, there are full translations of those records in Lynn Nelson’s A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Italian Ancestors (Betterway Books). The book is out of print, but you might be able to find used copies online or at a library. Some websites also offer, for a fee, a human to translate your letter or document, or you can find a translator using the Association of Professional Genealogists directory.

7. Research guides

FamilySearch also offers free Italian research helps. Listed along with the letter-writing guide mentioned in source 6, you’ll find links to maps of Italy, a Historical Background of Italy, the many pages available at the Research Wiki with details on how to find and read Italian civil records, several step-by-step guides for finding and using different types of Italian records, and an Italian Genealogical Word List you can download and print.

8. Italian Genealogical Group

Though it’s based in New York City, the Italian Genealogical Group has membership worldwide. The group’s website includes a database of surnames and Italian localities members are researching. If you find a name and place that match your interests, click the e-mail link and ask for the name of the submitter.

The IGG site also has several databases of records, but they’re mostly for New York. You’ll find naturalization and vital records indexes, including New York City Deaths, 1898 to 1948, and New York City Births (this index spans from 1878 to 1909). Links let you print forms to request the records from the city’s vital records office.

While you’re on the site, also look at the organization’s newsletter articles on Italian genealogy. Not all the newsletters go online, so you may want to consider joining to get future issues.

9. POINT

Pursuing Our Italian Names Together was a membership organization which existed from 1987 until 2013. Its quarterly journal, POINTers: The American Journal of Italian Genealogy, is filled with articles on tracing Italian ancestry. The organization also sponsored a national conference every other year. Members of the Italian Genealogical Group (see number 8) have access to a 25-year archive of POINTers.

10. Mangia, mangia!

What would an article on Italian resources be without bringing up food? Being Italian and loving food go hand in hand. But how, you may ask, will that help with my genealogy?

The answer is that food preferences are regional and local in Italy. Just as learning social history helps you better understand your ancestors, researching their dietary habits might shed light on why the family always ate fish on Christmas Eve (a Southern Italian tradition) or preferred polenta (historically, a staple in Northern Italy) to pasta. Details like these not only give more depth to your family’s story, but they also provide ways to carry on the traditions of your heritage.

At the website LifeInItaly.com, you’ll find several helpful articles on Italian food and wine for the different regions. In the link for Nonna’s Food, discover bits of wisdom on food and spices in the Italian diet, as well as herbal remedies. You’ll also find recipes and tips for cooking pasta and making Italian bread and pizza. If you’ve ever wondered how good olive oil is produced, you’ll learn about that here, too. And while you’re on the site, check out the links for Heritage and History under the Culture tab at the top.

Maybe much hasn’t changed in the way you’ll research Italian ancestors, but there are more resources than ever before to help you fill in the gaps in your tree. Buona fortuna in your search!

Tip: Italian civil authorities began registering births, marriages and deaths in 1820 in Sicily and 1809 in many other areas.

Tip: See examples of handwritten Italian genealogy terms from old records on the FamilySearch Research Wiki.

A version of this article appeared in the July 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to Amazon and affiliated websites.