Despite being an overwhelmingly Catholic nation, Mexico has had a sometimes fraught relationship with the Church. But Catholic records are some of the longest-taken documents in Mexican genealogy—and, indeed, in the Western hemisphere—dating all the way back to the 1500s in some cases.

Understanding the history of Mexico and the Church during your ancestors’ lifetime will help you determine why certain records might be missing, or kept in unsuspected places. And diving into the baptism, marriage and burial records kept by the Church can take your family line back centuries.

Read on for this guide to Catholic records in Mexico, including where to find them on sites like FamilySearch and what details they may hold.

The Catholic Church in Mexico: A History

Catholicism first came to what is now Mexico in February 1519, when Spaniard Hernán Cortés started the exploration and conquest of what was to become La Nueva España (New Spain). As he explored Yucatán, he encountered Jerónimo de Aguilar, a Spanish Franciscan priest who had survived a shipwreck and was imprisoned by the Maya. Aguilar, who spoke both Maya and Spanish, became Cortés’ interpreter with the Maya people.

Upon conquering the ruling Mexica (Aztecs) in 1521, Cortés petitioned the Spanish monarch to send Franciscan and Dominican friars to the area to convert the vast indigenous population.

Many claim the Spanish committed genocide against the indigenous population, but the truth is more complicated. In fact, the Spanish allied themselves with many of the Aztecs’ rival tribes, and rewarded some (like the Tlaxcalans) with the rights of Spanish citizenship. The reduction or decimation of the indigenous population was largely due, instead, to diseases that came along with the Spanish. And many of Mexican heritage today have large amounts of indigenous DNA—myself included, with 30%.

As the Spanish expanded to almost half of the North American continent, the priests went with them or immediately followed. Settlers founded new towns and shortly after selected lands for church lots and missions. Religion became the official method of pacifying the indigenous population: If it failed, only then did the Spanish take military action against them.

In 1810, the priest Miguel Hidalgo started a movement to rebel against the bureaucratic government of New Spain. Little did he know that the movement would become a full-fledged conflict for Mexican independence. After years of fighting, Mexico obtained its independence in 1821. In subsequent years, the new Mexican government banned many symbols associated with Spain, while maintaining its Catholic roots.

In the 1850s, the Mexican government under President Benito Juárez issued a series of decrees that drew sharp boundaries between church and state. The Church had its lands confiscated and its authority subverted to civil authorities. All unions apart from civil marriages were declared annulled, and all cemeteries were declared public property.

Many of these reforms were codified into a new constitution in 1857. In turn, the Church excommunicated all civil officials who swore to support the constitution. This thrust the country into civil war between liberals (who wanted to lessen the role of the Church in Mexican government) and conservatives (who wanted to maintain it).

The Church found more support during the rule of Porfirio Díaz, who seized power in 1876 and served as president from 1877 to 1880 and 1884 to 1911. Díaz declined to enforce many of Juárez’s anti-clerical laws, allowing the Church to regain its role in many aspects of civil life.

Díaz was ousted in the bloody Mexican Revolution, leading to a new constitution in 1917. In it, the Roman Catholic Church was denied recognition as a legal entity. Religious education was forbidden, as were public religious ritual outside of churches. All Church property was seized by the federal government.

These latest restrictions led to armed rebellions throughout Mexico in what would become known as the Cristero War. Many priests went into hiding, while others conducted masses in different ranches so as to not be arrested. Tensions finally ended in 1929, when the government made some concessions.

Mexican Catholic Church Records: What They Contain

Thankfully for us, the Catholic Church in Mexico has records that go back all the way to the 1550s. Here’s a roundup of the records most relevant to genealogical research.

These records were kept in Spanish (rather than in Latin) and were handwritten. If you need help reading old handwriting, I’ve got a guide on my website.

Baptism records

The amount of detail in baptism records varies by time (with more recent records having more information), but they generally include:

- Name

- Date of baptism

- Age and/or date of birth

- Place of birth

- Names of parents and grandparents

Here are some examples throughout the centuries. Priests often used a similar format when creating records, though (as we’ll see with all church records) record-keeping practices and level of detail both varied from priest to priest as well as over time.

For these examples, I’ve indicated the baby’s name in red, the date in green, and the parents’ names in blue. Each image is accompanied by a translation.

![Baptism record with translation that reads: "In 22 of March, I the priest [?], baptized Joseph Spaniard legitimate [son] of Diego Tremino and Batriz de Quinta-Nilla, his wife. His godfather was Balthasar Venagas"](https://www.familytreemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Mexican-Catholic-Baptism-1565-1024x337.jpg)

![Baptism record with translation that reads: "In the Parochial Church of the Village of Allende on the 5th day of September of eighteen eighty, I Presbyter[ian] Francsico Castañeda interim priest of the same solemnly baptized and placed the holy oils and sacred confirmation to Pedro of eight days old, legitimate son of Don Jose Angel Marroquin and Doña Francisca Perez. Paternal grandparents Manuel Marroquin and Maria Guadalupe Rodriguez. Maternal grandparents Narciso Perez and Maria Juana Tamez. Godparents were Don Pedro Moya and Doña Juana Marroquin who I advised of their dispatched obligation. I give faith – Francisco Castañeda"](https://www.familytreemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Mexican-Catholic-Baptism-1880.jpg)

Tip: Look for additional information in the margin. In this record, the margin in this 1880 record translates to:

September 5 of 1880

Entry No. 1899

Pedro of 8 days

old born in Zaragoza

Marriage records

Just as with baptisms, marriage records can be found as far back as the 1550s and can contain a wealth of information. Also, the further back you go, the less information they will contain. You can expect to find:

- Names of the bride and groom

- Date of wedding

- Place(s) of residence

- Names of parents

- Whether previously married

- Places of birth

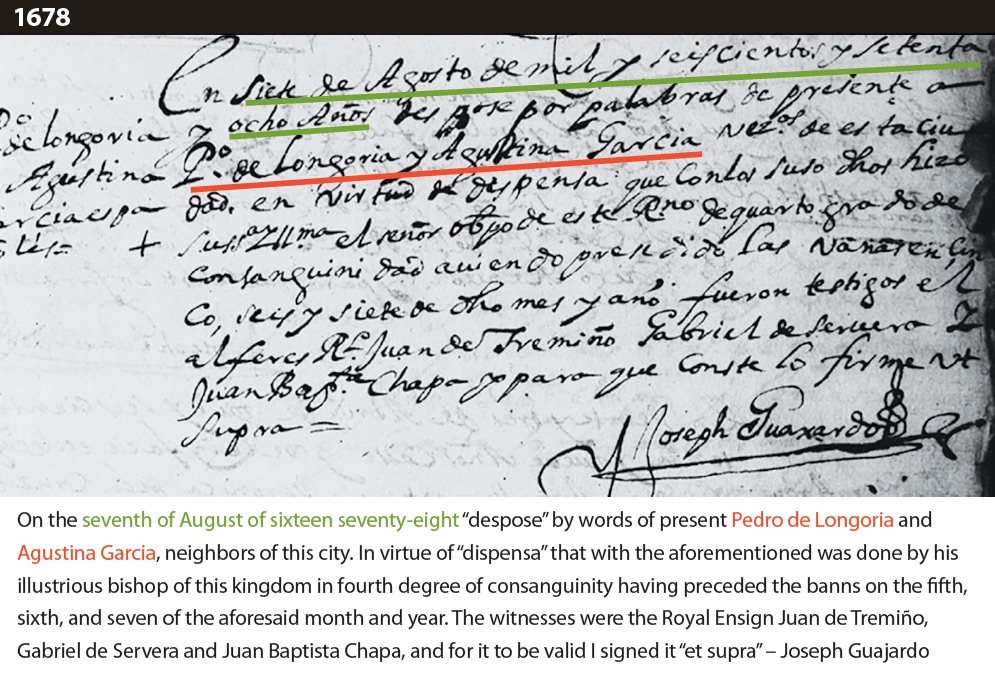

For these examples, I’ve indicated the couple’s names in red, the date in green, and the parents’ names in blue (when listed). Each image is accompanied by a translation.

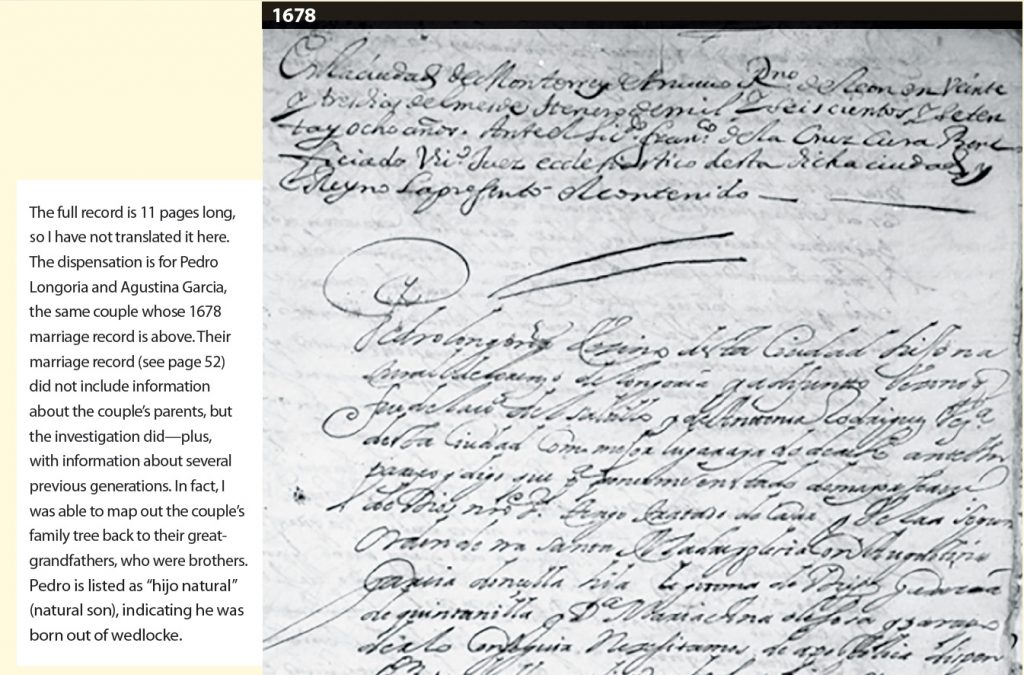

The 1678 record notes the bride and groom were related by blood, and thus the bishop had to grant his permission for them to get married (indicated by the word “dispensa”). This is your cue to look for a marriage dispensation.

![Marriage record with translation that reads: "On the second day of January of eighteen ten: Having read the banns in this my Parochial of Cerralvo and of the one in Mier in three festive days that were the 26, 27, and 28 of this past December, and there having been no canonic impediment than that of relatedness by consanguinity of third degree on both sides [?] Illustrious Sr. of Don [?] Feliciano Marin bishop of this Diocese: I the priest of this [?] and ecclesiastical judge married “Infansie Eclassie” Jose Rafael de la Garza Spaniard original and neighbor of Mier and resident of “la Manteca” going on five years, son of Francisco de la Garza and Maria Cayetana Peña, with Maria Tomasa Sanchez Spaniard original and neighbor of “los Hoyos” daughter of Juan Jose Sanchez and Maria Gertrudis Garcia. Being witnesses Don Jose Antonio Perez and Manuel Villarreal. I blessed them afterwards [?] of the celebration of mass [?] and I sign it. - Jose Andres Garcia"](https://www.familytreemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Mexican-Catholic-Marriage-1810-1024x573.jpg)

Marriage investigations

A marriage dispensation was needed whenever the couple was related by consanguinity (blood relationship), affinity (marriage or sexual relationship), or ultramarino (a birthplace other than Mexico). Dispensations (or investigations) can contain a wealth of information, provided the archdiocese was recording them during your ancestor’s life time. I’ve personally been able to find dispensations back to the 1650s, though you should research record availability in your ancestor’s area.

You can expect to find:

- Names of the bride and groom

- Places of birth or residence

- Names of parents

- Names of grandparents, great-grandparents, and further generations if necessary

- Witness reports

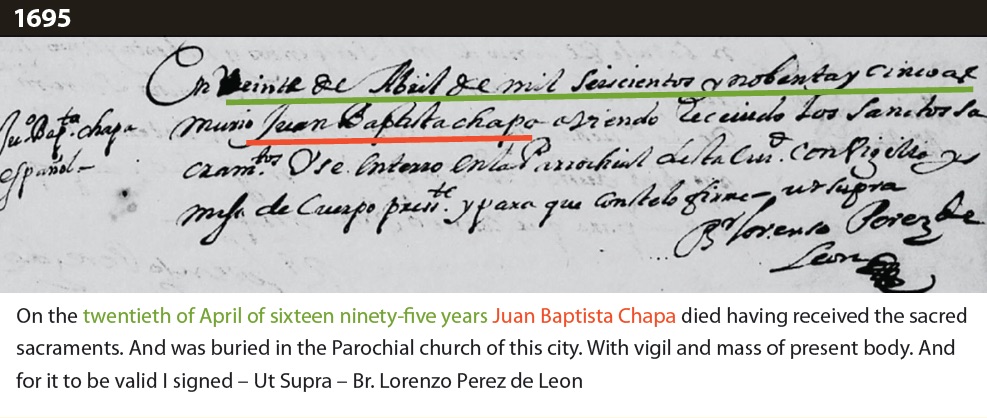

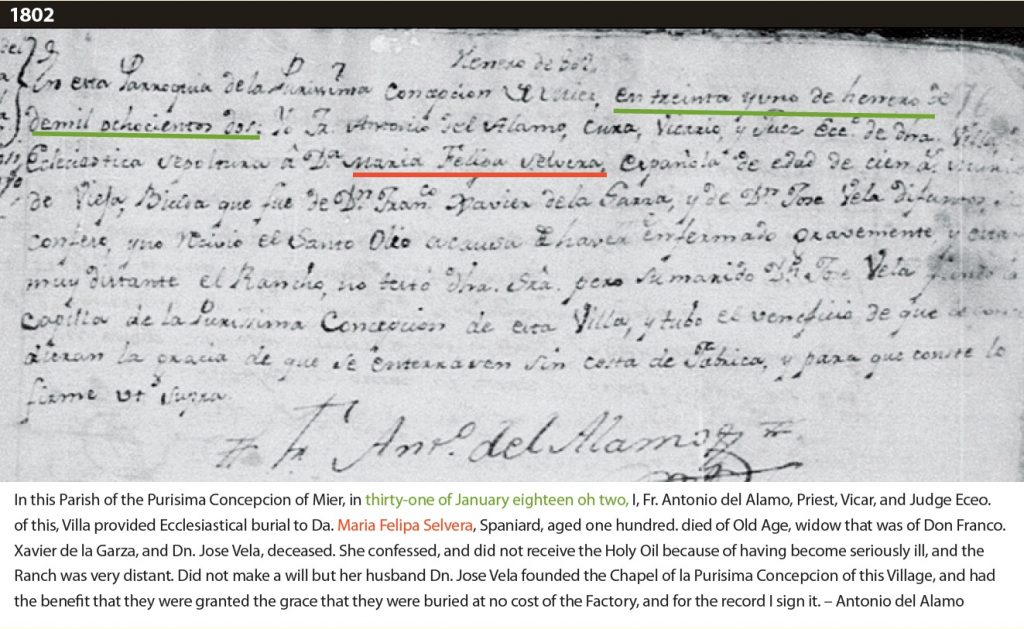

Death records

In reality, Catholic “death” records actually document a person’s burial, and so may have been created up to several days after the actual death. As with the other records we’ve discussed, death records contain less information the further back in time you go. You can expect to find:

- Cause of death

- Place of death

- Name of spouse(s) and sometimes children

- Names of parents

- Place of burial

For these examples, I’ve indicated the deceased’s name in red and the date in green. Each image is accompanied by a translation.

Finding Records

As you may have had noticed, the records in this article came from FamilySearch, which is the best place to find Roman Catholic Church records for Mexico. The site has millions of record images from Mexico, plus thousands of microfilm reels.

Go to FamilySearch’s home page, then select Search > Catalog from the main menu. Enter the town/city name in the place box to determine if the site has church records for that locality. You can also search from the main Records form, but not all records have been indexed.

Indeed, you’ll sometimes have to browse through entire collections of digitized microfilm to find your ancestor. To do so, go to Search > Records, then click Browse All Published Collections. In the Place toolbar, select Mexico to open a dropdown that shows states. I chose Tamaulipas, which filtered FamilySearch’s collections to just those from that state.

From there (if the collection has been indexed), you’ll be prompted to search just within that collection. But if the collection isn’t, you’ll need to drill down to a municipality or city to start accessing images.

For marriage investigations—which largely haven’t been indexed—you’ll need to have a microfilm and page number before you can browse the collection. Two searchable websites will help you find that information: Guadalajara Dispensas for the Archdiocese of Guadalajara and Valladolid Dispensas for the Archdiocese of Valladolid/Michoacán/Morelia. A two-volume book set, Index to The Marriage Investigations of Diocese Guadalajara, might also prove useful.

Other record indexes include the Spanish American Genealogical Association in Corpus Christi, Texas, which has indexes for many towns in the Mexican states of Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas.

You can also look for books that serve as indexes to unindexed records using Google or WorldCat. One such example is Sagrada Mitra de Guadalajara Antiguo Obispado de la Nueva Galicia Extractos Siglos XVII–XVIII (Guadalajara marriage excerpts from the 17th and 18th centuries).

The only way to obtain records that haven’t been digitized is to go to the individual churches. If you do so, be prepared to be turned down. Many churches and parishes will not let you look at their registers. If you are lucky and have exact dates, you can request certified records for a fee. Note that records may have been sent to the diocese for safekeeping.

If you can’t travel, then you’ll need to find a Mexican genealogist to do the search for you. You can search for professionals on Google or through the Association of Professional Genealogists.

With coverage dating back to the 1500s, Roman Catholic records can be a valuable addition to your family history research. I hope that I’ve shown you the great information you can find in them.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the September/October 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: April 2025