Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

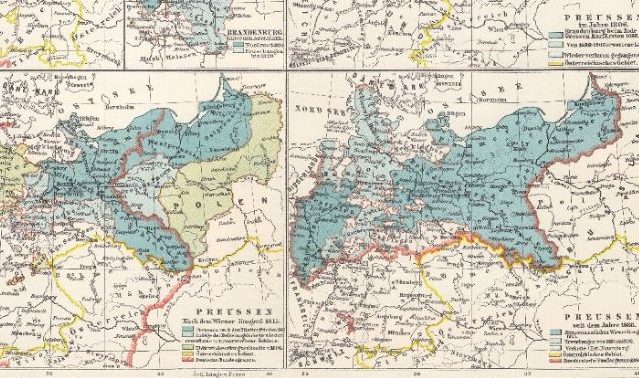

So your ancestors are listed in records as “Prussian,” but you can’t find Prussia on modern maps of Europe. What gives? Before being absorbed into Germany, Prussia was a major military and economic power in Central Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries. Let’s take a look at Prussian history to see what we can learn about your Prussian ancestors.

Throughout history, “Prussia” could refer to several states of varying sizes and levels of autonomy. Let’s take a quick walk through the state’s history to better understand what Prussia was and what lands may have been considered part of it.

Where Did Prussia Get Its Name?

The name “Prussia” itself originated in the Middle Ages when pagan tribes inhabited the area adjoining the Baltic Sea between Pomerania and Lithuania. These tribes were conquered by the Roman Catholic Order of the Teutonic Knights in the 1200s, who organized the territory into a fiefdom of Poland.

The region was ruled by a succession of the Knights’ grand masters for the next few centuries. But when Albert I of the Hohenzollern family became the Knights’ grand master, he converted to Lutheranism. He recast the Teutonic States as the secular Duchy of Prussia in 1525, becoming the first major Continental ruler to break from the Catholic Church’s authority during the Reformation.

Prussia became the crown jewel of the Hohenzollern family. The Hohenzollerns first held a tiny territory in southern Germany, but gained substantial land in the east in 1415 when it acquired Brandenburg (including the city of Berlin), notable for being part of the Holy Roman Empire’s electoral college. The addition of Prussia in the 1520s greatly expanded the family’s eastern holdings, and the whole Hohenzollern state became known as “Brandenburg-Prussia” in the 17th century.

The Hohenzollern’s acquisition of Prussia coincided with the later stages of German speakers moving into the area—the so-called Ostsiedlung. This strengthened bonds across the disparate German states, with the mighty Prussia significantly bolstering its strength and influence by the 17th century.

Kingdom of Prussia

Prussia was declared its own kingdom—outside the boundaries of the Holy Roman Empire—in 1701. Out of deference to the Holy Roman Emperor (who the Prussian king nominally held allegiance to), Prussia’s monarch secured the title “King in Prussia.” The odd coinage stemmed from the tradition of the Holy Roman Empire not allowing for the rank of king among the empire’s constituent states. As a result, the Hohenzollern ruler was styled “Elector of Brandenburg” inside the empire and “King in Prussia” outside of it.

During the whole of the 1700s, the Hohenzollerns embarked on a mission to unite its scattered territories into one contiguous land mass. Along the way, the long-reigning Frederick the Great (1740–1786) conquered Silesia from the Austrians in the 1740s.

Then, Prussia—along with the Austrian and Russian Empires—dismantled the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a state large in land area but weak in military. The final result connected the family’s Prussian holdings with the rest of its territory—and wiped Poland off the map of Europe for more than 100 years.

As a consequence of this increase in power, the King “in” Prussia designation grew into the King of Prussia in 1772. At that point “Prussia” (Preussen in the German language) and “Prussians” came to be the shorthand for all Hohenzollern possessions—much to the chagrin of many the kingdom’s later conquests.

The Congress of Vienna and the German Confederation

Like most of Europe, Prussia was rocked by French Emperor Napoleon I has he stormed across the continent in the early 1800s, capturing some territories Prussia had gained during the partitions of Poland. Prussia cemented its status as a major European power, however, when the Congress of Vienna in 1815 returned the lands Napoleon had captured.

Prussia also benefited from another result of the Congress of Vienna: the German Confederation. The loose affiliation of German-speaking city-states didn’t include Prussia, but Prussia exerted its influence over the region. Prussia established a trade union with the Confederation states that excluded Austria, allowing Prussia to edge out its rival to become the dominant German-speaking state in the region.

Soon afterward, Prussian King Frederick William III decreed a union of the kingdom’s major Protestant denominations, the Lutherans and the Reformed (Calvinists), into Evangelische, the name under which the vast majority of today’s Protestants in Germany will be found.

Before then, most Prussian commoners were Lutherans, but the Hohenzollerns and much of the nobility had been Calvinist since the early 1600s. (Some congregations dissented from the union and became known as the “Old Lutherans,” even emigrating to the United States to avoid persecution.)

During the 1800s, Prussia dominated the smaller and weaker constituent states of the Empire, continuing its drive toward a contiguous territory with several stages and drawing it into conflict with Austria (the other prominent German-speaking power). First, there was the “soft” solution of forming a customs union (Zollverein) with other German states that excluded Austria. Then Prussia outright annexed Hanover and parts of Hesse after the two states sided with Austria in an 1866 war.

Prussia also led the charge against the French in the Franco-Prussian War, resulting in the 1871 declaration of the Second German Empire. The King of Prussia assumed the additional title of Emperor of Germany, and Prussia became the pre-eminent state in a federal German empire.

Is Prussia the Same as Germany?

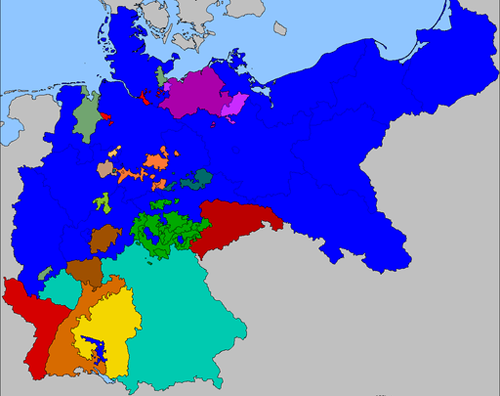

Not exactly. At its peak Prussia included half of modern Poland and all but southern Germany. Though itself one of Germany’s many states, the kingdom of Prussia was comprised of: West Prussia, East Prussia, Brandenburg (including Berlin), Saxony, Pomerania, the Rhineland, Westphalia, non-Austrian Silesia, Lusatia, Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover and Hesse-Nassau.

However, historians recognize Prussia as the predecessor to a unified German state. Otto Von Bismarck, Prussia’s prime minister, was instrumental in Germany’s creation. Seeing an opportunity to expand Prussian influence (and dreaming of a unified German empire), Bismarck seized territory through wars with Denmark and Austria. He also declared a new alliance among Prussia and the German states, called the North German Confederation (1867–1871).

Does the Country of Prussia Still Exist?

No. After goading France into war (and quickly winning), Bismark negotiated a unified German Empire in 1871. Prussia remained the dominant power in the German Empire until its dissolution in 1918 after World War I.

Along its way to the top of the German heap, Prussia became a synonymous with militarism. The German Empire was dissolved after its defeat in World War I, but Prussia remained a state of the interwar Weimar Republic. It wasn’t until after World War II that “Prussia” was erased from the map of Europe.

Because of Prussia’s prominence in German history, you can often find the same resources for Prussian ancestors as you would for your “German” ancestors. You can find a list of online resources specifically for Prussian ancestry on the FamilySearch Wiki.

But all this history—including the 20th-century decline of “Prussia” as a nation-state—doesn’t change how natives of the land were referred to in the many documents referencing Prussia from the 1800s and early 1900s. (Aside, of course, from giving researchers some mental anguish!)

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: June 2025

What Was the Prussian Garde du Corps?

Q: My great-grandfather was a member of the Prussian Garde du Corps before 1884. Where can I learn more about the Garde and my great-grandfather’s service?

A: First, you must make sure your ancestor really was part of the Prussian Garde du Corps, which began in 1740 as an elite cavalry unit and became the German emperor’s bodyguard. If all stories about such service were true, elite units wouldn’t be very elite. You’ll need to be open to the possibility that your great-grandfather was in some other unit, in case his Garde membership is just a family story.

If you have documents stating your ancestor’s association with the Garde, regimental histories should list the details you want. For example, Count Ferdinand von Brüuhl’s The History of the Prussian Garde du Corps During the Campaign of 1866 (Helion & Co.) provides casualty lists, information about honors awarded and more. (Most regimental histories will be in German.)

Also, since the Garde was garrisoned at Potsdam, Germany, you might write (in English) to a German repository and ask if they have regimental histories or other information on the unit. Try these two repositories, listed in Raymond S. Wright III’s Ancestors in German Archives (Genealogical Publishing Co.):

During the time your ancestor lived in Prussia, boys had to enlist in the military; their enrollment records, called stammrollen, show their birth dates, parents’ names and other remarks, including their assignments to particular military units. The FamilySearch Library has microfilmed some of these records, but you’ll need to know your ancestor’s specific birth village to access them. For example, knowing he lived in Pommern, a region along the Baltic Coast, isn’t enough—you’d have to determine he was born in Franzburg or another town.

Once you’ve found the birth village, you can search the FSL’s online catalog to see if the library holds stammrollen from that location. Then you can use Meyers Ortsund Verhehrs-Lexikon des Deutschen Reichs (called Meyers Gazetteer for short) to find out which military command office (in German, Bezirkskommandoamt, abbreviated BKdo in Meyer’s) the village reported to. The records will be cataloged under that town’s name.

In either case, it would help to learn some German or get a translator. Few German military records have been translated into English; you might consult Horst A. Reschke’s German Military Records as Genealogical Sources (self-published, out of print). It’s available on microfilm at the FSL.

This question appeared in the the June 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: June 2025.

How Can I Find a Map of Prussia that Shows Locations of Towns?

Q: My husband’s ancestors are from “old Prussia.” With all the wars and resulting changes in place names, how can I find a map that shows the locations of their towns?

A: Before German unification in 1871, the Kingdom of Prussia was the most powerful of the many independent German states. Old Prussia refers to former Prussian provinces that are now mostly in non-German countries.

First, find out whether the towns you seek are still in Germany—you’ll need to use a German road map or atlas for that. The most detailed one, according to Larry O. Jensen of the FamilySearch Library (FSL), is Der Grosse ADAC Jubilaeums-Atlas Deutschland. A less-detailed map book found in many libraries is Auto Atlas 1995/96 Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Families often change the spelling of ancestral places with succeeding generations, so try variations of the town names.

Finding places no longer in Germany takes a few extra steps. Since most of the once-German villages are now in Poland, first “translate” the old German place name into the modern Polish name, then pinpoint it on a modern-day map.

Check the 1912 Meyers Orts-und Verkehrs-Lexikon des Deutschen Reichs (also called Meyers Gazetteer) to confirm the old name. It’s available at many large genealogical libraries, on microfilm at the FSL and from Genealogical Publishing Co.

Determining the Polish name depends on when Germany lost the village. For towns that became Polish after World War I, consult Deutsch-Fremdsprachiges Ortsnamenverzeichnis. For territories ceded after World War II, use Amtliches Gemeindeund Ortsnamenverzeichnis der Deutschen Ostgebiete unter Fremder Verwaltung. Both of these resources are available as books and microfilm from the FSL.

The best modern Polish maps are in the 1997 edition of Polska Atlas Drogowy. It’s available at the FSL and in some academic libraries.

A version of this article appeared in the June 2004 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: December 2024

Related Reads

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for site to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in an affiliate program through Genealogical Publishing Co. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.