Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

“Tear down this wall!” Who could forget US President Ronald Reagan’s 1987 challenge to Mikhail Gorbachev to destroy the Berlin wall as proof of his commitment to glasnost (transparency) and perestroika (restructuring)?

Built in 1961, the wall was a symbol of communist oppression, and Gorbachev, then the General Secretary of the Soviet Union’s Communist Party, was promoting change in the Eastern Bloc. East Germany opened the wall Nov. 9, 1989.

If you’ve attempted to trace your Russian roots, you likely know a lot about walls—brick walls, that is: Russian genealogy has been full of roadblocks that keep researchers from getting to the important details about their ancestors. If you’re discouraged from hearing nyet one too many times in your family search, take heart—the research is getting easier.

“The astonishing thing about Russian genealogy is the fact that it is possible at all. Wars, revolutions and ignorance have destroyed a significant part of written records,” notes Russian research expert Mikhail Kroutikhin. Although genealogy flourished in czarist Russia at the beginning of the 20th century, he notes, it was quashed after the revolution in 1917. “Persecution—even massacres—of people belonging to ‘wrong’ classes discouraged the transition of family memories to young generations,” he says. “Only a decade ago have Russian genealogists started to come out in the open.”

Certainly, researching roots in Mother Russia is fraught with challenges: record destruction, recent political instability, language barriers and the historical persecution that led past generations to keep details mum. For family history researchers used to fairly complete and easily accessible American records, the challenges of Russian genealogy might seem especially difficult to surmount. But the strategies described here will help you get past the hurdles that otherwise could potentially thwart answers about your Russian ancestors.

1. Start at Home

As you begin your search for Russian ancestors, you’ll apply the basic principles of genealogy: Start with home and family sources to identify the immigrant’s name and his/her town or village of origin. Ask them plenty of questions, and be sure to always ask where key events took place.

In addition to any available family resources, you’ll need to check all accessible North American records you can find before moving on to research across the ocean. Some key US and Canadian resources to investigate for clues to the town or village your immigrant ancestor came from: censuses, immigration and naturalization records; birth, marriage and death records; military draft and service records; cemetery burial cards; tombstone inscriptions; and obituaries.

2. Note the Names

In order to successfully research across the pond, you’ll need to know your immigrant ancestor’s original name. Many immigrants Americanized their names once they arrived in the United States. Some adopted the English equivalent, while others chose a similar-sounding name or made the spelling more American. (Despite popular lore, Ellis Island immigration officials didn’t change people’s names.)

Many changes were inevitable: If your ancestors hailed from the former Soviet Union or Russian Empire (Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians), their names would be transliterated from the Cyrillic to the Roman alphabet. Russian names spelled in Cyrillic letters have various—and sometimes peculiar—versions when spelled in French, German or English. For example, the letter V easily becomes W or FF. One resource to check is the online Dictionary of Period Russian Names.

Consider Russian naming customs, too, as Jonathan D. Shea and William F. Hoffman advise in their book Following the Paper Trail: A Multilingual Translation Guide: “Generally, Moscow has forced even non-Russians under its control to comply with Russian customs regarding names.” The system works like this: Each person has a given name, a patronymic and a surname. The patronymic usually ends in –ovich for men or –ovna for women. You’ll need to pare down names to their “root” forms to track your ancestors.

Orthodox and Catholic families frequently named children for saints, selecting one whose feast day was close to the child’s birthday. Jewish families named children after close deceased relatives. Jews in the Russian Empire didn’t adopt surnames until the government began requiring their use in the early 19th century.

3. Grasp Geography and History

Russia is the world’s largest country, covering almost twice the territory of the next-largest nation, Canada. It boasts the world’s eighth-largest population, with 149 million people.

Historically, Russia’s population consisted of Slavic tribes:

- East Slavs: Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians

- West Slavs: Poles, Czechs and Slovaks

- South Slavs: Bulgarians, Croats, Macedonians Serbs and Slovenians

Russia was an independent country for many centuries, then following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent Russian Civil War of 1918 to 1930, it became the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), a republic of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, Russia has been known as the Russian Federation. To gain a deeper understanding of Russia’s rich and complex history, consult the books and online resources listed in this article’s toolkit boxes.

Russia today shares land borders with 14 countries, including Norway, Finland, Poland, Ukraine, China and North Korea. The United States and Japan aren’t far away, with small stretches of water (the Bering Strait and La Pérouse Strait, respectively) in between. The Russian Federation spans nine time zones, so you can appreciate the need to get a handle on the geography: otherwise, pinpointing locations of your ancestors’ records will be next to impossible.

You’ll want to familiarize yourself with Russian terms for administrative divisions. Imperial Russia (aka the Russian Empire) was divided into gubernias (provinces), which were divided into uyezds (districts). Soviet Russia and Ukraine and other former Soviet republics were, and are still, divided into oblasts (provinces), which were and are divided into raions (districts). The Caucasus—a geopolitical region at the border of Europe and Asia, situated between the Black and the Caspian sea—sometimes use the term krai instead of raion for district.

Archives from all over the former Soviet Union concentrate their holdings according to oblast borders. You’ll need to know both the old and the new jurisdictions—in particular for smaller places. For example, the FamilySearch catalog, which lists the vast holdings of the Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City plus digitized records at FamilySearch.org, uses the new jurisdictions for Ukraine, but the old ones for Russia. Most of FamilySearch’s Russian and Ukrainian microfilms are from the Imperial time, and of course those old documents refer to the old jurisdictions.

Maps, atlases and gazetteers (geographical dictionaries) will be your friends as you sift through old and new borders. Start with the Palgrave Historical Atlas of Eastern Europe (Palgrave Macmillan), and view a map of 1912 Russian Empire jurisdictions. Read up on the FHL’s collection of gazetteers.

4. Survey the Records

When you’re ready to cross the pond, avoid the temptation to dive right in without some preparation. You should first create a research plan that outlines the “who, what, when, where and why” of what specifically you wish to accomplish. This is called a genealogy research plan.

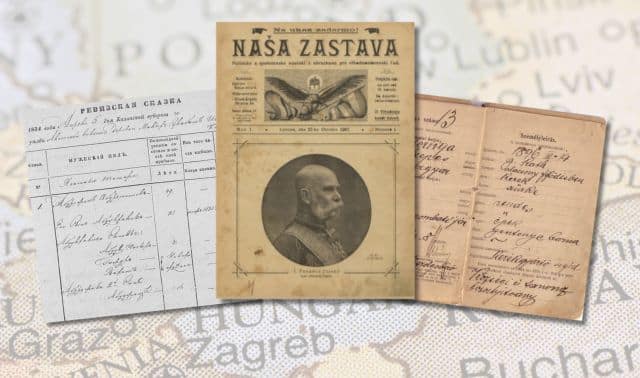

Keep in mind that most records you seek will have to be accessed in person at Russian archives—though that doesn’t necessarily mean you must travel to Russia, as we’ll explain later. Among the helpful resources online and on microfilm: the Russians to America Passenger Data File, 1834–1897, available via the National Archives and Records Administration’s (NARA) Access to Archival Databases, and Records of Former Russian Agencies (otherwise known as Russian Consular Records) held by NARA. See record group M-1485 for the United States and M-1742 for Canada. An index to the records is The Russian Consular Records Index and Catalog by Sallyann Amdur Sack and Suzan F. Wynne, available on microfilm from NARA. Search the FamilySearch catalog, too, for Russian Consular Records to find microfilm you can order for a modest fee to view at your local FamilySearch Center.

Library and Archives Canada’s Likacheff-Ragosine-Mathers (LI-RA-MA) collection (MG 30 E406) includes 11,400 files of Jewish, Ukrainian and Finnish immigrants’ passport applications and questionnaires created between 1898 and 1922. The index and digitized images series are available online.

Record-keeping in the Russian Empire mostly resembled the practices elsewhere in Europe. Vital records were the purview of the church before the government stepped in. Older parish registers are usually at archives, while more recent ones (within the past 75 years) are in civil registration offices, explains Kahlile Mehr, former Slavic Collection Manager for the FHL and FamilySearch.

The government took 10 poll-tax censuses, referred to as revision lists (revizskie skazki), between 1719 and 1859. They’re organized by place, then by social class, such as nobility (dvorianstvo), peasants (krest’iane), Cossacks (kazaki) and Jews (yevreyski). Surviving revision lists are in regional and historical archives, as are remaining copies of the 1897 census of the entire empire. FamilySearch has some digitized records (indexes, images or both) online.

For more help, consult the FamilySearch Wiki. Although FamilySearch has made great strides in bringing data collections online, its Russian collections only scratch the surface of what may exist. Remember to keep checking back for new collections.

5. Look for Patterns

Immigration patterns can help you theorize where your ancestor came from and why he may have migrated. Early Russian immigrants to America tended to settle in Alaska and along the West Coast. Larger numbers arrived after 1880.

The largest influx came during the “great migration” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with 2.3 million immigrants from czarist Russia arriving in the United States between 1871 and 1910. Groups settled in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oregon, the Dakotas, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Virginia. Russian Jewish songwriting legend Irving Berlin was among this wave of immigrants. When the Soviets loosened immigration restrictions in 1969, thousands left, including many Jews.

If the trail back to Great-grandpa grows cold, try cluster genealogy—the process of studying your ancestor as part of a group, or “cluster,” of relatives, friends, and neighbors and associates. The cluster approach can help you find (or confirm) details you might miss by looking only at an individual immigrant ancestor. Scour US census records for relatives or others from the same town, look at traveling companions on passenger lists and note names of witnesses on baptismal and marriage certificates, and naturalization petitions.

6. Access Archives

For records not available via FamilySearch, you’ll need to determine which Russian archive houses them. The Russian Federal Archive Service has contact information for all archives and links to each archive’s website when one exists. You can use Google to translate the basic information on the site; a more in-depth knowledge of Russian may help you use it more effectively.

Be prepared for your research to take you to archives for the countries bordering Russia if your ancestor came from areas once part of Russia, including Belarus, Ukraine, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. If you’re researching in early historical time periods, be aware that regional archives keep records dating back only to about 1790. You might find earlier information in federal archives in Moscow or St. Petersburg. You have three options for getting records from Russian archives:

- You can send a written request, although this usually requires advance payment and long wait times, with varied responsiveness and no guarantee of positive results.

- You can travel to Russia and do the research yourself—a costly and often difficult route.

- You can hire a researcher local to the archive to find the records you need, send digital copies and even translate them for you. This is often your best bet, because a Russia-based researcher can speak the language and knows the repositories. Fees vary, Kroutikhin says, depending on the volume of the records to be translated and explained. To avoid surprises, always ask the researcher for an initial estimate up front. Let the researcher know if you have a budget cap you can’t go beyond. Also make sure you provide as much identifying information about the record as you know: the exact name of the ancestor in the record, his birth date and place, and the date of the record.

To find a reliable researcher, check with the Association of Professional Genealogists, ProGenealogists, or Routes to Roots (specialists in Jewish research), or ask for recommendations from fellow genealogists.

7. Learn a Little Language

As you search and especially once you get to the records you need to view, you’ll need to figure out some Russian language basics (or find someone who can translate). Although Russian is among the most difficult languages for English speakers to learn, you can dabble with short and basic DIY translations using free tools such as BabelFish, Google Translate, and the Russian Dictionary iPhone/iPad app.

To be sure you don’t miss any important information, learn a little more about the Russian language. Begin with the series of free tutorials on FamilySearch.org, which will acquaint you with the Russian alphabet (a variation of the Cyrillic alphabet); explain Russian names, dates and key terms; and teach you the basics of reading Russian genealogical records including birth, marriage, and death records. FamilySearch also has a Russian genealogy word list you can download for free. Also see the language and other research helps on the Doukhobor Genealogy Website.

If you decide to take a chance on mailing a request to a Russian archive, you’ll need to prepare your correspondence in Russian—don’t expect archive staff to speak or read English. Jonathan Shea has excellent sample letters in Russian in his book Going Home: A Guide to Polish American Family History Research (Langline). Although the book focuses on Polish research, it has several pages of Russian vocabulary in addition to the sample letters.

For more-accurate results, hire a human translator (rates will vary). See if your local college or university language department can recommend someone, or check out Cucumis, Freelang and Linguanaut.

With these tools and research strategies, your Russian roots discoveries soon will speak for themselves—and tear down your research brick walls.

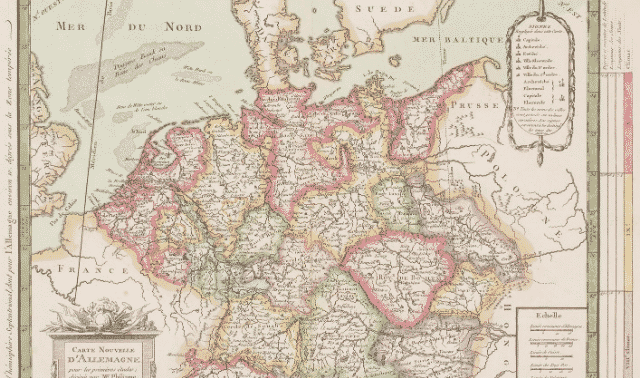

8. Trace Germans from Russia

Germany was a fatherland whose “children” included enclaves in areas of Central and Eastern Europe that never were part of any German empire. Those who settled in Russia numbered about 1.8 million by the end of the 19th century. Collectively known as “Germans from Russia,” these include the Volga Germans (who settled near the Volga River in southern European Russia), Bessarabians, Hutterites, Volhynians (from what’s now Ukraine) and others. Baltic Germans, or Deutschbalten, settled in areas now in Estonia and Latvia, formerly part of Russia.

Wars have rendered most of these German enclaves extinct, but the descendants of these groups include hundreds of thousands of Americans. You may be one, if your genealogical findings indicate Russian or Baltic origins for ancestors who spoke German.

Also use websites such as the Germans From Russia Heritage Collection, the Germans From Russia Heritage Society, and the Odessa German-Russian Genealogical Library.

Tip: The Library of Congress’ European Reading Room website offers a PDF download of Cyrillic alphabet transliterations.

Tip: When studying dates in Russian records, remember that Russia didn’t adopt the Gregorian calendar until 1918. Use Steve Morse’s calendar conversion tool.

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Timeline

859 The Rus’, Viking traders, establish first Russian state at Novgorod

860 Cyrillic alphabet invented

1147 Moscow founded

1237 Tatars defeat Kievan Rus’

1560 St. Basil’s Cathedral completed

1582 Russia occupies Siberia

1598 Time of Troubles includes famine and transition between ruling dynasties

1698 Peter the Great westernizes Russia

1784 First permanent Russian settlement in North America, on Kodiak Island

1849 Moscow Kremlin is completed

1861 Russian serfs are emancipated

1866 Fyodor Dostoyevsky publishes Crime and Punishment

1867 Russia sells Alaska to the United States for $7.2 million

1917 Bolsheviks overthrow the provisional government that was set up after Czar Nicholas II was dethroned

1918 Ukraine and Baltic states gain independence

1920 Writer Isaac Asimov is born in Russia

1957 Russia launches Sputnik I

1987 Gorbachev launches the glasnost policy

1991 The USSR dissolves

2001 Mir space station is retired