Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

From the mid-1840s to 1930, nearly 1.3 million Swedes left for the United States—placing the departures, as a proportion of a European place’s population, behind only the British Isles and Norway.

“Peace, vaccination and potatoes,” as one historian put it, had caused Sweden’s population to double between 1750 and 1850. But as Swedes worried less about war, smallpox and starvation, they began to run out of land and looked west to Nordamerika. By 1910, almost one in five of the world’s Swedish population lived in the United States, clustering in states such as Minnesota, California, Illinois, Washington and Michigan.

The records they created by emigrating and in their new country can help you identify the parishes your Swedish ancestors left. Voluminous church paperwork records in the home country can tell your family’s story as far back as the 17th century.

If your idea of exploring your Swedish heritage is a trip to Ikea, we have good news: It’s never been easier to investigate your Swedish ancestors—no little hex wrenches required. Here are the key records to consult when studying Swedish genealogy.

First: US Records

Before you turn your attention overseas, start by investigating home sources: obituaries, old photos, family Bibles, journals, and books or correspondence written in Swedish. Your goal is find your ancestor’s last parish of residence in Sweden, then (if possible) a birth year. Follow up with interviews of family members.

Then, find any stateside church records. Many Swedish-American churches kept records as meticulous as those back home (see No. 2); some may even mention year of arrival. The Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center in Illinois is one reliable source, and Ancestry.com has Lutheran records (though they don’t generally mention the parish of origin in Sweden).

Only after you’ve established some basics about your Swedish ancestor should you look for US-side immigration records. Many Swedes arrive in the United States before Ellis Island opened in 1892. But those who came through New York may well have come through Ellis Island’s predecessor, Castle Garden. Search records of both immigration stations through the Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation website.

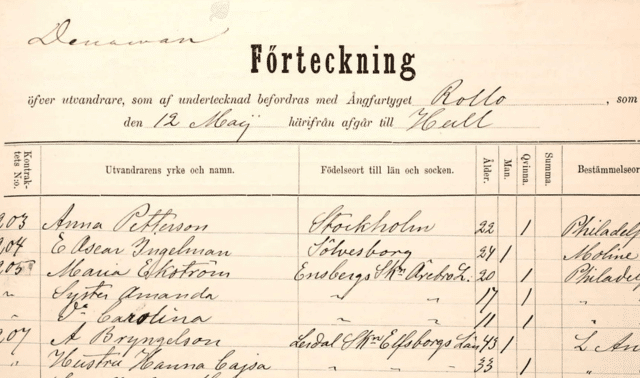

Note that few Swedes (especially those who came in early decades) sailed directly from Sweden to the United States. They may have left from Göteborg (Sweden’s second-largest city) to Hull, England, then by train to Liverpool or Glasgow before boarding a vessel there.

1. Emigrant Lists

US passenger records can help establish your ancestors’ Swedish origins, but they’re unlikely to contain the key to unlocking Swedish records: the name of the home parish. Fortunately, Sweden has its own, typically more detailed emigration records.

Ancestry.com has a collection of passenger and other records (Emigranten Populär), including those from eight Swedish ports and a dedicated collection for Göteborg (Gothenburg).

ArkivDigital has the records from the four primary ports: Göteborg, Malmö, Stockholm and Helsingborg. These emigrant records, called Emihamn, were compiled from police records of departing Swedes.

Swedish churches not only tracked emigrants to “Amerika” but also between parishes. Online collections of church records can be searched for these records of persons moving in (inflyttnings) and out (utflyttningslängder). Ancestry.com has a collection in Swedish.

It’s also possible Swedish emigrants might have sailed from Hamburg, Germany. Check Ancestry.com for these records. Others left via Copenhagen and can be found in Denmark emigration indexes on Ancestry.com and MyHeritage, or directly through the Danish archives. Departures from Oslo, Norway, would be recorded in the records of that country’s Digitalarkivet.

When searching for Swedish emigrants, try every possible name variation and use search wildcards when possible. On Ancestry.com, for example, Jans* will find both Jansdotter and Jansson. Consider that first names might vary, too; Hannah could be Johanna or even Anna. An ancestor’s birth date can be the key to finding the right emigrant among many similarly-named Swedes (who may have changed their names in America, anyway).

2. Church Records

Why is it so important to discover your ancestors’ parish back in Sweden? Unlike in the United States, where vital records were kept by government authorities, the role of vital recordkeeper in Sweden fell to the established church (the Lutheran Church of Sweden) for centuries. Sweden itself didn’t begin keeping civil vital records until 1950.

The oldest Swedish church records (kyrkböcker) date from 1608 to 1615. Nationally, the Church laid down regulations for records in 1686; adherence throughout the kingdom was not widespread until the 1720s, however. Centralized rules for Swedish recordkeeping lagged until about 1860, when standardized printed forms were issued.

Even then, however, records continued to vary from place to place until 1894, when another standardization initiative was implemented. All pre-1895 church books were sent to a regional archive (landsarkiv) for safekeeping. If you find gaps in the parish records, these originals likely were lost or destroyed—just in case, though, you can check neighboring parishes.

ArkivDigital boasts the largest collection of Swedish church books, which you can search via a name index. You can also browse 102 million record images there.

TIP: Use birth years has a kind of identifier when reviewing church records, especially if your ancestor had a common name.

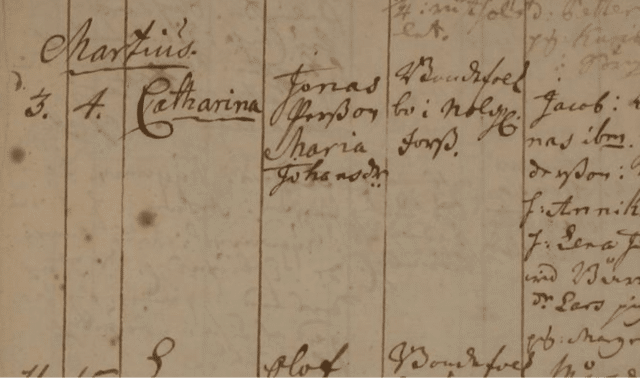

Births and baptisms

Records of birth (födde) typically include the names of parents, christening witnesses, birth and christening dates, and the child’s name and birthplace. In early records, the columns show only date (birth/christening), name, name of parent(s) and witnesses.

Other Swedish birth and baptism records (födde och döpte) may have a few more columns or more-formal headings, typically:

- Number

- Name

- Born (month/day)

- Christening (month/day)

- Parents’ names and residences

- Witnesses’ names and residences

- Conditions

Marriages

Swedish records of marriage (vigde) usually include the names and residences of the couples, date and place of the marriage, and sometimes names of their parents.

Columns could be quite varied in Swedish marriage records, but often represented:

- Number

- Date of banns

- Marriage date

- Name and residence of groom and bride

- Remarks (facts about groom, bride’s sponsor, inheritance information)

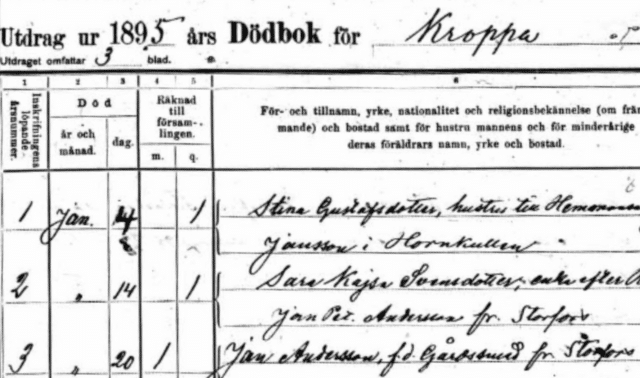

Deaths and burials

Swedish death (döde) records commonly include the burial place, age at death, cause of death, and last residence and occupation. Standard headings include:

- Number

- Death date

- Name

- Residence

- Age

- Cause of death

Some death records helpfully give the birth date rather than age, which you can use to quickly scan for an ancestor. You may also find columns that mark married (gift) or unmarried (ugift).

Other church records

In addition to vital records, the state Lutheran churches recorded when a child—typically as a teenager—was confirmed and ready to receive his or her first communion. These records may list details such as parents’ names and residences, and can even partly substitute for birth records when those can’t be found.

Swedish confirmation records (konfirmationslängder) were not required, however, and some parishes didn’t keep them at all. Check online collections of church records, by parish; ArkivDigital and the Riksarkivet (SVAR) are generally the most complete.

You may also find communion records (nattvardsgång or kommunionlängder). They can be used as a sort of census substitute, as they show that an individual was in a parish at a particular time. These were often notated in household examination records (see the next section), rather than in standalone records.

Churches also kept track of vaccinations, which were crucial given the ravages of smallpox before a vaccine was available. Sweden recorded the shots in household examination books, using a variety of abbreviations: v, vac or vacc, as well as s or sm for “smallpox.”

3. Censuses and Household Examinations

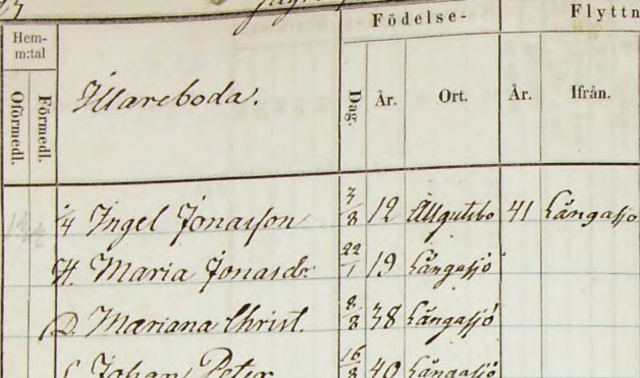

Sweden did not take genealogically useful “censuses” (per se) until recently. But it does have a wealth of annual church records called “household examinations” (husförhörslängder) that can be used much like a census. You can also find collections of these clerical surveys online, searchable as though they’re true censuses.

First introduced by Bishop Rudbeckius in the 1620s, surveys listed all the farms in the parish, with names and vital statistics about everyone living there. They even included personal notes (fräjd) from the pastor about these members of his flock. Revisions to the forms in 1894 downplayed the counts’ religious emphasis.

Household examination books for many parishes date from the 18th century. They update the status of parishioners and their households—all listed by name—and span about five to 10 years per sheet (typically on two facing pages). The intervals vary, simply depending on how much space the parish needed before starting a fresh set.

Unlike censuses, household examinations reflect changes within that span as they happened: births, marriages, deaths, and families moving in or moving out. These notations may appear at the far right of the page(s), so be sure to study the entire entry. When a person died within a span of a book, their annual tick mark stops.

As a result, the husförhörslängd provides a valuable cross-reference to other Swedish church records for the same parish. A useful strategy, in fact, involves working back and forth between household examination records and church vital records for the same parish. Church birth records helpfully include the names of parents, which you can use to find the parents’ household in the husförhörslängd.

Make note of the specific location within the parish in which you find a record, so you can more readily find ancestors in the other records. With a little luck, you can trace a family backwards in time—revealing husförhörslängd entries, births, marriages and deaths—to the beginning of a parish’s written records.

Just as in US census records, however, expect spelling variations and erroneous dates in these Swedish enumerations. The shifting patterns of patronymics versus permanent surnames, as well as the use of nicknames, can also lead to surprises and roadblocks.

Key to identifying your correct Swedish ancestors is a birth date, which follows through from one survey to the next and functions almost like a Social Security number in the United States. When forced to browse pages of challenging handwriting, scan for a birth date to help spot an individual in the crowd.

Household examination records are available on several websites, including:

4. Land and Probate Records

Swedish records of land ownership and usage cover 1570 to the present, and sometimes contain information of genealogical value. Most Swedish land records created before 1875 have not historically been indexed; that year, new records called lagfartsböckerna and inteckningsböckerna were introduced.

FamilySearch holds land records for many places in Sweden. Try to identify the relevant district court (häradsrätt), then drill down in the FamilySearch Catalog for it and click on “Land and Property.” Sweden’s national archives has also scanned many of these records. Select the record type on the Databases page; options include land registers (jordeböcker, about 1630 to 1750) and land certificates (lagfartsböcker, 1875 to 1933).

Probate records—court records that describe the distribution of an ancestor’s estate after death—often pre-date even church vital records. In Sweden, an act passed in 1734 made it mandatory to conduct an inventory of a deceased’s estate (bouppteckning), although only an estimated one-quarter of the population actually did so. The preamble to this inventory can often contain genealogically useful information.

Estate inventories and probate records have been indexed for many Swedish häradsrätt, and can be found online at ArkivDigital and the Riksarkivet. These indexes as well as the actual records are organized by district court.

5. Military Records

If your ancestors (like my great-great-uncle) served in the military before leaving Sweden, you can easily search for them in the general muster rolls (generalmönsterrullorna) at ArkivDigital.

The main index includes “allotment” (indelta) regiments—essentially, draftees—and enlisted regiments from 1683 to 1883. A “quick find” index covers only allotment regiments. More-detailed information on soldiers from 1902 to 1950 can be found in a collection of military service cards.

Riksarkivet has scanned images of army rolls as far back as the 17th century and muster rolls, organized by regiment. You can also search a collection of 500,000 entries in the Central Soldiers Registry, all of which come from the allotment system. Though not complete, the registry covers 1682 to 1901.

Start your Swedish research with the readily available church records, then supplement with other collections as necessary. You’ll be well on your way to finding your Swedish roots and appreciating your heritage—maybe more easily than putting together that Ikea bookcase.

Related Reads

A version of this article will appear in the March/April 2025 issue of Family Tree Magazine. It also includes material originally published in the October 2006 and December 2016 issues.