I still have an insatiable appetite for the past. Like most genealogists, I want to learn about my ancestors’ clothes, food, politics, jokes, games and music. But I no longer have to daydream about going back in time. I’ve discovered a “time machine” that lets me glimpse my forebears’ day-to-day experiences firsthand: historical re-enactments.

The concept is just what you’d imagine — people wearing period costumes act out real (or close-to-real) history. To the uninitiated, re-enactments may seem like a kind of bygone Disneyland. But these events are definitely more about historical accuracy than just playing dress-up.

Re-enactments usually depict a specific event, often a battle. For example, participants in the Custer’s Last Stand re-enactment <custerslaststand.org> in Hardin, Mont., recreate the famous post-Civil War battle, as told from the American Indian perspective. In Mississippi, re-enactors play out the Civil War Battle of Corinth <www.wprogerscorinthms.com/reenactment.htm>, during which the Union and Confederate armies fought for control of the strategically situated village.

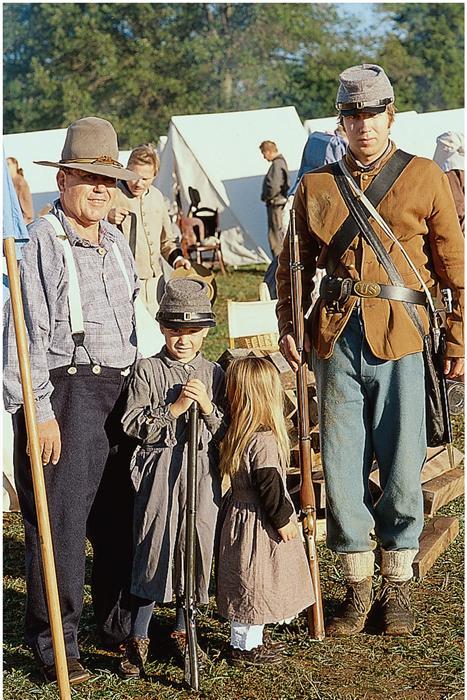

For the sake of educating the public, re-enactors may take part in make-believe battles or living history weekends, striving for historical accuracy in terms of the way soldiers fought, trained, cooked, ate and relaxed.

But re-enactments don’t deal only with bloodshed. At historic sites such as Massachusetts’ Plimoth Plantation <www.plimoth.org> and Old Sturbridge Village <www.osv.org>, actors offer a look at life long ago in an authentic setting. These sites usually remain open year-round, and primarily serve an educational function. Just how accurate are they? It’s possible your 18th-century Virginia ancestor could walk the streets of today’s Colonial Williamsburg <www.history.org> and feel right at home.

1. Take your place.

Depending when your family came to America, you can probably find a re-enactment showcasing that time period. Many historic sites and national parks offer living history weekends or encampments. For example, Illinois’ Fort de Chartres <www.illinoishistory.gov/hs/dechartres.htm>, one of three forts erected near the Mississippi River by France’s colonial government, hosts a two-day rendezvous featuring shooting competitions, military drills and 18th-century music and dancing each June. If your ancestors lived in French territory during the mid-1700s, you’ll get a feel for their experiences by attending the event.

Were your relatives among America’s first English settlers? If so, put Jamestown Settlement <www.historyisfun.org> on your travel to-do list. There, you can watch living history interpreters act out early-1600s life on the banks of Virginia’s James River. Or visit nearby Yorktown, which played an important role in both the Revolutionary and Civil wars. At the Yorktown Victory Center, you can walk through a re-created continental army encampment and see a 1780s farm, where interpreters demonstrate agricultural practices used in the years following the Revolution.

You can find more living history events and re-enactments by doing a little Web research. Visit the National Park Service (NPS) Web site <www.nps.gov> and click on Parks & Recreation, then Geographic Search to locate NPS-designated historic sites and parks in the places important to your research.

Say your Volunteer State ancestors made their living at a mill, and you’re curious what that work entailed. On the NPS Geographic Search page, select Tennessee from the scroll-down menu, or click on Tennessee on the US map. You’ll get a list of travel destinations within that state. If you click Great Smoky Mountains National Park and then In Depth, you’ll find lots of tourist information. Select History under Recreational Opportunities, and you’ll see that the park’s 1886 Mingus Mill offers demonstrations. Travel a half-mile south to the Mountain Farm Museum, and you can explore a log farmhouse, barn, apple house and working blacksmith shop — all built about the same time and probably resembling buildings in which your relatives lived and worked.

Next, log on to your favorite search engine (try Google <www.google.com>) and enter a phrase such as Indiana re-enactment (or Indiana reenactment). This search will return a slew of Hoosier State re-enactor groups’ Web sites. Look for current calendars listing upcoming events in your area.

Perhaps you’re more interested in a particular time period than a specific place. In that case, try a search such as “Spanish-American War” re-enactment or “Victorian era” “living history.” (Using quotation marks will help limit search results by turning up only pages in which the quoted terms — such as living and history — appear side by side and in that order). If your relatives served in the Civil War, you’ll likely be able to find re-enactments of the battles in which they participated. Know which regiments your Civil War vets joined? Surf over to the Civil War Archive <www.civilwararchive.com> to find a complete list of battles fought by those regiments.

2. Study and stock up.

2. Study and stock up.Approach a re-enactment the same way you tackle your family history puzzles. Preliminary research always makes a genealogy road trip go more smoothly; likewise, you’ll learn more at a re-enactment if you hit the library first. Many re-enactors are knowledgeable historians, and they can educate you about a specific time period — but the more you know upfront, the better questions you can ask.

For example, if you’re attending the annual Battle of Gettysburg re-enactment (see calendar, page 49), pull out a history book and learn why historians consider this three-day battle one of the most pivotal of the Civil War. You also might explore the Civil War Reenactors Web site <www.cwreenactors.com>, which will give you a feel for the whole re-enactor experience. You’ll notice how much genealogists and re-enactors have in common, particularly when it comes to preserving historic sites and cataloging cemeteries. Some re-enactor Web sites, such as the 11th Texas Cavalry’s <11texascav.org>, even have links to online genealogy databases.

Next, visit the Web sites of regiments attending a particular re-enactment; most provide details about the unit’s history, along with photos from past events. Some sites also contain educational articles on re-enacting, uniforms, codes of conduct and battle flags.

Once armed with information, stock up on film or digital memory cards and batteries for your camera, and hit the road.

3. Earn an A for accuracy.

Re-enactors will do everything possible to remove traces of the modern world from their sites — a process known in re-enactor slang as “defarbing.” Most encampments will have two or three tents open to the public; if a tent’s flaps are open, view that as an invitation to come in and look around. If the flaps are closed, stay out — these are the tents that hold sleeping bags, nylon jackets, coolers and other 21st-century wares you’re not meant to see, since no one wants to break the illusion. As you walk through an encampment, you’ll feel as if you really have stepped back in time. You won’t see or hear anything that wouldn’t have existed during that time period — as one re-enactor guideline stated, “You’d better have hard tack in your haversack and not Pop Tarts!”

To say that re-enactors pride themselves on accuracy is an understatement. There’s constant chatter on re-enactor message boards about how to defarb this and that. “My uncle will grind corn for grits,” wrote one Johnny Reb. Another re-enactor replied, “Corn products didn’t exist in the Confederate Army until 1863 — this stuff would be farby.”

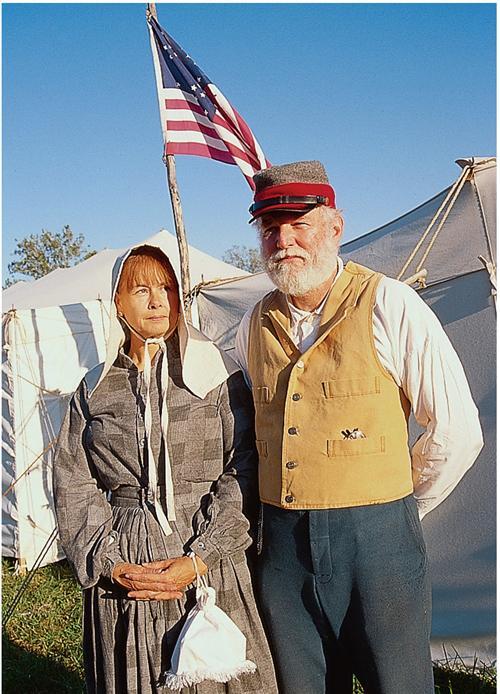

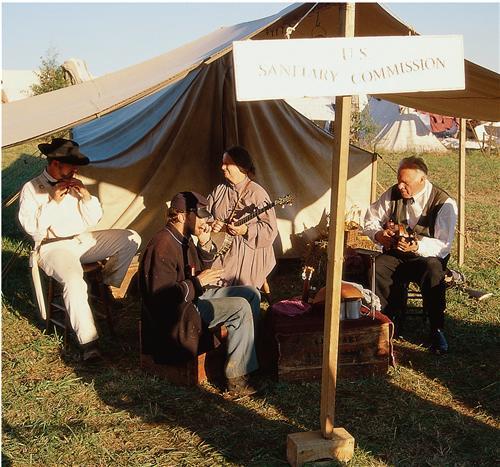

Some re-enactors buy period clothes from a sutler (re-enactor speak for “supplier”), and they favor items crafted from original patterns and reproduction fabric. Others, with the goal of total accuracy, sew their own clothes using hand-woven materials. During the Civil War, neither the Union nor the Confederacy issued standardized shirts, so you’ll see a wide variety of calico, cotton and flannel — some shirts made by the soldiers themselves; others by their hoop-skirted lady friends.

Strike up a conversation with these ladies and gents, and you’ll learn about period music, clothes, food and customs. Even male re-enactors can answer questions about period underwear, hoop skirts, corsets and fabrics. They’ll also explain what it was like for women awaiting their husbands’ returns.

Re-enactors strive for historical authenticity, from their reproduction clothes and accessories to the period songs they play at camp.

4. Play along.

If there’s one thing living history interpreters and re-enactors love, it’s being asked questions. “We want people to engage us,” says Tom Kelleher, research historian at Old Sturbridge Village. Keep in mind that re-enactors don’t want to come out of their roles, and they appreciate your “period” remarks just as much as you enjoy theirs. For instance, on one of my trips to Fort Abraham Lincoln <www.fortlincoln.com> in North Dakota, a re-enactor — knowing I was a writer — implored me to write to Congress about the abysmal conditions at the 1875 fort. Of course, I promised I’d do my best to get him better food and more pay.

Re-enactors, by virtue of their hobby (or in some cases, profession), become skilled historians. Many research not only the history of their military unit or village, but also the events that would have affected them had they lived during that time. At Colonial Williams-burg, for example, interpreters spend weeks learning the town’s history, and consequently become experts on Colonial life. Ask about their decisions to become patriots or loyalists, and you’ll learn more about Colonial-era politics than you would in any classroom.

Some of Williamsburg’s dedicated interpreters get to take on the roles of people who actually lived in the Colonial capital. These people spend their off-hours reading letters, diaries and other documents that will help them step into the shoes of a real person.

5. Capture the moment.

Wherever your research leads you, be sure to take lots of photos. Then when you get home, import the pictures into your genealogy software, and use them to illustrate reports and family history books.

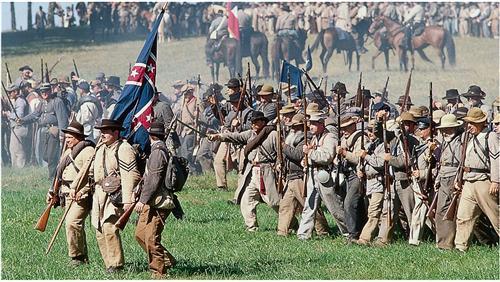

To photograph a battle re-enactment, you’ll need a long lens: Observers aren’t allowed on the battlefield. Although participants don’t shoot real bullets, they do use large quantities of black powder, as well as rifles that shoot 2- to 3-foot flames. Some re-enactors, although well-trained, have actually lost fingers or gotten other injuries in battles — so obey the rules and stay in the viewing area.

Since firing black powder produces a lot of smoke, stay upwind of the battle, or you’ll photograph all smoke and no action. Re-enactors take their own photos, but you may never see their cameras — they’ve grown adept at hiding equipment in knapsacks or shooting only when they’re concealed in heavy brush. If your goal is snapping battle scenes, talk to the re-enactors before the fight and ask where you should position yourself to get the best shots without being in the way.

6. Get inside the zone.

You might be thinking, “OK, re-enactors are passionate historians, but they can’t really know how it felt to live in another time, can they?” One last question to ask at an encampment is whether anyone has experienced a “time shift” or “zone” during an event.

Victor Judd, a Confederate re-enactor, has: When he’s facing 2,000 advancing “Yankees” and 20 blazing cannons, trying to load his weapon authentically, hearing his line sergeant yell and curse about keeping up a high rate of fire, and enduring the 100-degree heat in a wool uniform, he says, it’s easy to actually “feel” the period.

“Your mates aren’t dying to the left and right; you don’t hear the solid thump of a round in the chest of your best friend,” he says. “But in your mind all of that is happening, and you’re transported to another place.”

It’s a phenomenon that’s not always discussed openly, but one experienced by many re-enactors — and it could offer insight into your own ancestors’ experiences.