The holidays are a great time for nostalgia. It’s fun to imagine the opulence of a Victorian Christmas tree or the cheerful simplicity of a stocking-bedecked Rockwell-esque fireplace scene. But how close to reality are these rosy views of our ancestors’ days? After all, illuminating a genuine pine tree with burning candles wasn’t without its risk. And let’s not forget the bitter cold reality of living without indoor plumbing in December.

Still think things were better way back when? I give you this holiday and party-related trivia I dug up for my book Good Old Days, My Ass. Trust me—you’ll be glad you’re celebrating Christmas, Halloween and other holidays in the 21st century instead of the 19th.

Ho, Ho, No!

Kriss Kringle’s Christmas Tree, 1845. Image from Library of Congress.

Bah, humbug!

Until 1681 in New England, people who had a good time on Christmas could be fined five shillings. The Puritans and others considered secular celebrations of Christmas as wanton Bacchanalian feasts, and declared Dec. 25 instead a day of fasting and penance. Any celebrating, including feasting or just taking the day off from work, earned a fine.

Redcoat and green.

Christmas celebrating took another blow with the American Revolution, because the hated British tended to make a bigger spectacle of yuletime. American patriots came to link Christmas with Tories and Loyalists.

Seasons Greetings?

Christmas cards have long had a secular bent, depicting holly, mistletoe and plum pudding from the beginning. But some 19th-century Christmas cards took this to an extreme with bizarre and even vulgar scenes of scantily clad girls, devils, bugs and rats.

X-rated Xmas.

Victorians adopted the mistletoe from the ancient Roman mistletoe tradition of the Saturnalia. The Christmas custom of “kissing under the mistletoe” is a toned-down version of the sexual license of the Roman holiday.

Santa Gnome.

Before illustrator Thomas Nast gave Saint Nicholas a makeover in Harper’s Weekly, from 1862 through 1886, not-so-jolly old Saint Nick was variously depicted as a frock-clad gnome and a stern-faced bishop.

Tricky Business

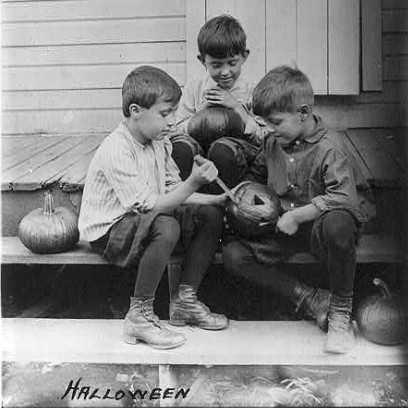

Three boys on porch steps cutting faces in pumpkins, 1917. Photo from the Library of Congress.

No treats, no trickery.

Halloween has had a hard time gaining acceptance as a holiday. The Puritan ethos of Colonial New England discouraged celebrations of Halloween, which originally took hold in America as a harvest festival in the southern states.

Conjuring Mr. Right.

For young women, Halloween was “San-Apple Night,” when it was believed girls could predict the name or appearance of their future husbands by magic with mirrors, yarn or apple parings, or by bobbing for apples.

We could be carving carrots instead of pumpkins.

Halloween caught on in America as Irish immigrants escaped Ireland’s 1846 potato famine. The new arrivals brought the jack o’ lantern with them. The original jack o’ lantern tale, however, is pretty grisly: Jack trapped the devil in a tree until the devil agreed that Jack, a notorious sinner, wouldn’t go to hell when he died. The devil gave Jack a burning ember from hell to light his way through the dark places of the earth, since heaven was forbidden to him, and Jack placed it in a lantern made of a carrot or turnip. Placing the “burning ember from hell” in a pumpkin proved more practical after the Irish got to America.

Sugar’s probably not the best way to calm them.

Some popular histories of Halloween maintain that “trick or treating” was popularized by adults as a way to bribe youngsters not to commit acts of vandalism. For example, Ze Jumbo Jelly Beans were packaged with the message, “Stop Halloween Pranksters.” As late as the 1950s, some adults viewed trick or treating as a form of extortion—or had to have the Halloween traditions explained to them by the costumed children at the door.

Life of the Party

A happy New Year 1867 – a happy New Year 1917 from the Library of Congress.

Holiday Hoopla.

The opulence of the “Gilded Age” led to some jaw-dropping extremes. One lavish New York dinner party took over the ballroom of the posh Sherry’s restaurant for a Wild West theme: Dinner guests, dressed in cowboy attire, ate on horseback—a peculiar indulgence made possible by leading several dozen horses into the restaurant, hooves padded to protect the floors, and tethering the mounts to tables. At another extravagant affair, thrown by Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt in 1883, the hostess came dressed as an electric light. More illuminating was the fact that the party cost $250,000, nearly $5.8 million in today’s dollars.

So much for birthday cake…

How uptight were the Victorians? It was considered shocking for a woman to blow out candles in mixed company, because to do so required pursing her lips in a manner that might be seen as suggestive.

Money can’t buy manners.

Fur baron John Jacob Astor once astonished guests at a fancy dinner party by wiping his hands using the dress of the lady seated next to him. Too bad he hadn’t read the popular American etiquette handbook that advised readers that they “may wipe their lips on the table cloth, but not blow their noses with it.” Another guide to manners cautioned members of polite society that it was considered impolite to sniff a piece of meat on one’s fork to make sure it had not gone bad.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2012 issue of Family Tree Magazine