A horoscope is an astrological chart or diagram representing the positions of the Sun, Moon, planets, astrological aspects and sensitive angles at the time of an event, such as the moment of a person’s birth. But where did Astrology originate?

If you’re among the estimated 70 million Americans who check their horoscopes every day, you’re continuing a tradition dating back perhaps 4,000 years. Many of our early ancestors wouldn’t make a move—whether launching a war or getting a haircut—without consulting the auguries of the stars and planets.

In its origins in ancient Babylon, about 2000 BC, astrology combined the science of studying the heavens with mystical beliefs associating celestial bodies with divine powers. Charting the constellations, planets, and the sun and moon helped ancient astronomers understand the recurrence of seasons and predict celestial events. By the 16th century BC, they had compiled a comprehensive reference known as Enuma Anu Enlil, consisting of 70 cuneiform tablets recording 7,000 heavenly signs.

Back then, however, astronomy and astrology were interchangeable, much as alchemy combined with actual chemistry. So practitioners of this Babylonian “star cult” also sought to predict more personal futures; the oldest surviving individual horoscope dates from 410 BCE.

Ancient Egypt developed an early form of astrology, too, in which the solar year was divided into 36 equal segments of 10 degrees each called decans. India and China also had their own astrologies, with India’s showing Babylonian influences.

Astrology in Ancient Greece and Rome

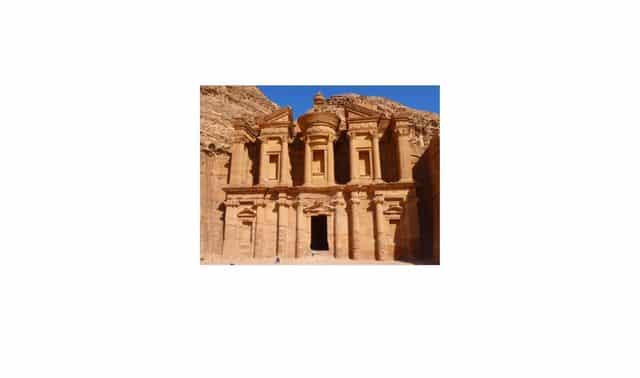

The ideas of Babylonian astrologers also spread to Greece and Rome. Their 12-part division of the heavens, whose earliest extant expression is in a cuneiform dating from 419 BC, took its name of “zodiac” from the Greek zodiakos (meaning “circle of little animals”). In 280 BC, the Babylonian priest Berossos founded an astrology school on the Greek island of Kos, which helped spread the zodiac in the Hellenistic world. Babylon was also known as Chaldea, and “Chaldean wisdom” came to be synonymous with astrological divination.

Romans took Chaldean wisdom seriously, carrying around sheets of papyrus that told them which times of the day were favorable or unfavorable for even mundane activities like shopping or bathing. Although Julius Caesar is said to have ignored divinations about his impending demise, subsequent emperors employed whole cadres of astrologers. (Roman emperors also periodically banned ordinary citizens’ use of astrology, lest the stars foretell their death or overthrow.) Romans produced some of the most important works of astrology. Early in the first century, Marcus Manilius penned Astronomica, which today is the oldest surviving astrology textbook. Claudius Ptolemy, who lived in Alexandria in the second century, wrote Tetrabiblos, which laid the foundation for much of Western astrology for millennia. Like many early astrological texts, Arabic scholars preserved it; it was reintroduced into Europe in 1138.

But not everyone in the ancient world was sold on astrology. As early as 156 BC, Carneades, the Athenian philosopher and ambassador to Rome, argued that the heavenly bodies are too distant to affect events on earth. Moreover, he pointed out, individuals born at the same time go on to lead completely different lives. Others born at the same time as Homer, for example, became neither poets nor famous.

Star-struck in the Middle Ages

By the 13th century, astrology was again part of daily life in Europe, influencing fields from medicine—in which doctors calculated the stars’ positions before surgery—to literature. Geoffrey Chaucer referenced astrology throughout his Canterbury Tales, noting in his opening verses that the sun “hath in the Ram his halfe cours yronne.” In Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, astrologer Guido Bonatti is depicted in the eighth circle of hell, where those who attempt to predict the future are condemned to have their heads turned around to look backwards. In real life, Bonatti authored a key astrology textbook, Liber Astronomiae, about 1277, and advised Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II as well as the governments of Florence, Siena and Forlì.

Despite Nicolas Copernicus’ disruptive discovery that the earth circles the sun—not the other way around, as presumed in ancient astrology—the practice continued to gain popularity during the Renaissance. Even astronomer Johannes Kepler, a prominent advocate of the Copernican worldview, argued that astrology was valid even in a heliocentric universe. He thought the powers of the stars and planets represented dormant images in the human mind—a view similar to that espoused in the 20th century by psychologist Carl Gustav Jung.

What’s Your Sign?

Although astrology faded under the glare of the Enlightenment, the mystical “theosophical” movement of the late 1800s helped spark another comeback. So did the popular press, for which William F. Allan—known as “Alan Leo” after his zodiac sign—founded an astrological publishing house in London. Though scorned by serious astrologers, Allan’s “shilling horoscopes” caught on with the public. He urged his fellow astrologers to avoid specific predictions and instead practice “the science of tendencies.”

The first newspaper astrology column—forerunner of those by Sydney Omarr and Jeane Dixon—was published in Britain’s Sunday Express. After the birth of Princess Margaret in August 1930, the editor asked astrologer R.H. Naylor to do her horoscope. Naylor safely predicted her life would be “eventful.” Asked to create more forecasts, Naylor asserted that “a British aircraft will be in danger” between Oct. 8 and 15—close enough to the actual crash of the R101 airship outside Paris on Oct. 5 to earn him a weekly column.

Although Naylor initially focused on “natal charts” using the positions of the stars at the time of a person’s birth, his “What the Stars Foretell” column soon expanded to “sun signs.” These simplified predictions based on the 12 signs of the zodiac offered casual readers fortune-cookie-like guidance headlined “Tendencies for Everybody.”

Naylor badly missed the tendencies leading Europe into World War II, however, writing in May 1939 that readers should not “look to Europe as the seat of conflagration. Actually the danger lies in the Mediterranean, the Near East and Ireland—on the sea and sea coast rather than inland.” He warned that “childless marriages” and “the failure of agriculturalists” were the real dangers to civilization, not the Nazis.

Wartime paper shortages led to Naylor’s column and other Express features being cut in 1942.

Decades after Naylor’s death in 1952, astronomers from the Minnesota Planetarium Society reported that the moon’s gravitational pull on the earth has made his “sun signs” system off by roughly a month. Rather than being a Virgo, Naylor would actually have been born under Leo. The 2011 report also added a new, 13th sign to the zodiac—Ophiucus, for those born between Nov. 29 and Dec. 17.

Timeline of Astrology

Interesting Astrology Facts

- Prominent British astrologer Alan Leo was twice prosecuted on charges that he “did unlawfully pretend to tell fortunes.” The first case was dismissed for lack of evidence; he lost the second, in 1917, and was fined five pounds.

- A 1985 study published in Nature found that professional astrologers were unable to match individuals’ star charts with actual personality test results any better than random chance.

- When astrologer and self-proclaimed psychic Jeane Dixon died in 1997, her last words were said to be, “I knew this would happen.”

- This article originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of Family Tree Magazine.