From caveman times, humanity’s never-ending struggle to put food on the table (or table-shaped rock, as the case may be) always been twofold. First, our ancestors had to hunt, gather or; later, grow and harvest their food. Then they had to find some way to preserve whatever couldn’t be eaten immediately. But scavengers and even insects that might horn in on ancient leftovers were the least of their worries, as our forebears soon learned the hard way: Bacteria too small to see — much less to understand, until Louis Pasteur came along in 1861 and disproved that microorganisms generate spontaneously — could swiftly make food inedible best, and deadly at worst.

For millennia, our ancestors preserved their food by drying, smoking, salting or sugaring it. These processes all had the side effect of altering the flavor and/or texture of the food being preserved. This was a good thing (think of bacon … mmm), but not always.

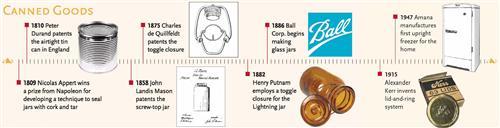

Then 150 years ago, a 26-year-old New Yorker, John Landis Mason, figured out to seal glass jars with a screw top so the food inside wouldn’t spoil-while still making the contents easily accessible later. He gave his name to the Mason jar-a term that’s persisted long after the expiration of his 1858 patents — and sparked a home-canning boom that lasted until the widespread adoption of home freezers. (Why it’s called canning rather than jarring is a conundrum lost in the mists of history.)

Mason was hardly the first to tackle the jar-sealing challenge. Early in the century, Napoleon had offered a prize of 12,000 francs to anyone who could preserve food for his armies. One of his subjects, a chef named Nicolas Appert who’d spent 14 years on precisely this puzzle, claimed the reward about 1809 with a convoluted process involving corks and tar.

Almost simultaneously, in 1810, Englishman Peter Durand patented the tin can, and his countrymen have been eating “tinned” food of all sorts ever since. Cans were slow to catch on across the Atlantic, however: The first US patents were issued in 1825, and the cans weren’t mass-produced until about 1850. Even aside from their tendency to impart a metallic taste to food, though, tin cans were impractical for home canning.

Glass jars were much more user-friendly. Like cans, jars could be filled, heated to kill any microorganisms inside and then sealed against future contamination. But how to seal the jars? In addition to being cumbersome, Appert’s solution presented a fresh challenge when cooks wanted to use the food — hacking through the tar and fishing out the cork.

Two employees of an American glass-making firm, Robert Arthur and Joseph Borden, each patented wax-sealing methods, in 1855 and 1858, respectively. The Willoughby and Kline companies popularized stopper jars, which employed a rubber gasket, in the 1860s. About the same time, the Millville Atmospheric Fruit Jar came along with a clamping approach, also requiring a special gasket. Although sold into the 1890s, clamping jars were costly and prone to rust.

Mason’s solution, patented Nov. 30, 1858 (a date later immortalized in glass on countless canning jars), was far more elegant. A tinsmith by trade, Mason devised a machine that could cut threads into the zinc lids, matching the threads molded into the tops of the glass jars. A rubber ring in the lid created the seal, and the screw-on design maintained it. His patent, No. 22,186, described the innovation as “new and useful Improvements in the Necks of Bottles, Jars &c. especially such as are intended to be air and water tight, such as are used for sweetmeats.”

The home-canning boom begun by Mason’s eponymous jar fueled further innovations. In 1875, Charles de Quillfeldt patented an alternative, toggle-style closure, whose best-known exemplar was the Lightning jar-named for the speed at which it could be closed or opened. Though never as popular among home canners as the Mason jar, the design caught on with beer bottlers and still can be seen on Grolsch bottles.

Two other now-familiar names built on the basic Mason-jar design. William Charles Ball and his brothers, originally in the tin-can business, switched to glass fruit jars in 1886. After relocating from their native Buffalo, NY, to Muncie, Ind., the brothers made their “Ball jars” the industry leader and almost as famous as the Mason jar. The Hermetic Fruit Jar Co., founded in 1903 by Alexander H. Kerr, added not only another famous name in glass but an essential innovation. In 1915, Kerr produced a two-part Mason-jar lid: a flat disk with a permanently attached gasket plus a separate, threaded metal ring. The ring and the jar could be reused, as they are by home canners today.

Both Ball and Kerr jars are now made by Jarden Home Brands, which bought out Ball Corp. in 1993. The familiar scripted Ball and Kerr logos continue to appear above the block letters spelling out, in glass relief, “Mason.”

But John Landis Mason never reaped the financial rewards to match his lasting fame. His patents were so specific that others could successfully claim their designs were different enough to fall outside the patent protection. Louis R. Boyd, whose jars became almost as well-known as Mason’s, patented his own Improved Locking-Ring in 1868.

After Mason’s patents expired in the 1870s, two big companies swept in to dominate the fruit-jar business-first the Consolidated Fruit Jar Co. (CFJ), which had merged with Boyd’s firm in 1871, and then in the 1880s, the Hero Fruit Jar Co., known by its “Hero Cross” symbol. Not even Mason’s own name remained his. The Mason jar trademark became generic, much as befell such brand names as zipper. All but penniless, Mason died in 1902.

He didn’t live to see the Prohibition-era innovation of another use for Mason jars — as a container for moonshine, an association almost as common today as the jars’ breakthrough role in preserving food.

Call in the Preserves

Devour more home-canning history with these resources:

• 1,000 Fruit Jars by Bill Schroeder (Collector Books)

• A Brief History of the Home Canning Jar

<www.pickyourown.org/canningjars.htm>

Clan Boyd Society International

• The Collector’s Guide to Old Fruit Jars by D.M. Leybourne (self-published)

• Frank H. McClung Museum

University of Tennessee, 1327 Circle Park Drive, Knoxville, TN 379967, (865) 974-2144, <mcclungmuseum.utk.edu>

• The Fruit Jar Works, 2 volumes, by Alice M. Creswick (self-published)

• Jarden Home Brands

• Kovel’s Price Guide to Antiques and Collectibles

<www.kovels.com/priceguide/kovels-bottle/1997/fruitjar>

•The Leader Jar: Fruit Jar Collectors

• Long Island Antique Bottle Association

<www.longislandantiquebottleassociation.org>

• Minnetrista Cultural Center antique Ball jars collection

1200 N. Minnetrista Parkway, Muncie, IN 47303, (765) 272-4848, <www.minnetrista.net>

• Museum of American Glass

1501 Glasstown Road, Millville, NJ 08332, (800) 998-4552, <www.wheatonarts.org/museumamericanglass>

• Philip Robinson Fruit Jar Museum

1201 W. Cowing Drive, Muncie, IN 47304, (765) 282-9707