The next time you photocopy a record for your family tree files, pause and say a little thank-you to the unknown inventor of the Rectigraph, which ushered in the modern document-copying era 100 years ago. And save some gratitude for Chester F. Carlson: In 2008, we’ll celebrate the 70th anniversary of his invention of xerography — making possible the Xerox copier.

Before these breakthroughs, our ancestors had no simple way to copy existing documents. Perhaps one of your 19th-century ancestors was employed as a copy clerk, copyist, scribe or “scrivener” — the humans, like Dickens’ Bob Cratchit or Melville’s Bartleby, who once did the work of copying machines.

More than a century before the Rectigraph came along in 1907, however, office-machine entrepreneurs thought up a variety of ways to duplicate documents as they were being created. Most of these techniques relied on complex combinations of special inks, oiled papers and screw presses; only a few copies could be extracted from any one document, and only within a few hours of its writing, before the ink dried.

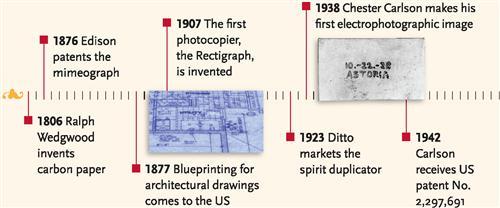

Englishman Ralph Wedgwood invented carbon paper in 1806. Not until the 1870s, though — after the advents of the typewriter and greaseless carbon paper — did this become a practical office alternative.

For mass duplication, companies began selling desktop printing presses as early as the 1850s. In 1874, Italian inventor Eugenio de Zuccato patented the first stencil-copying process. He was soon followed by none other than Thomas Edison, who could arguably be called the father of the mimeograph machine. In 1876, Edison

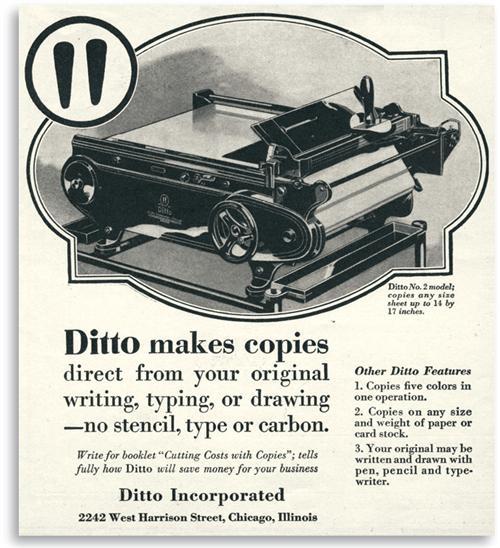

The “ditto” machine-whose aroma was so familiar to generations of schoolchildren-began about 1876 with the invention of the hektographic process, which used a special aniline ink, gelatin and rollers. The Ditto company introduced mechanized gelatin duplicators in 1910 and “spirit” duplicators, eliminating the messy gelatin, in 1923.

The machines were cumbersome and expensive. Early Rectigraphs and Photostats cost $500 to $1,000 — the equivalent of $10,000 to $20,000 today — and each l½×l4-inch print cost six cents. Both companies were eventually absorbed (Rectigraph in 1935 by Haloid Co. and Photostat by Itek Corp. in 1963) and their pioneering copying methods scrapped.

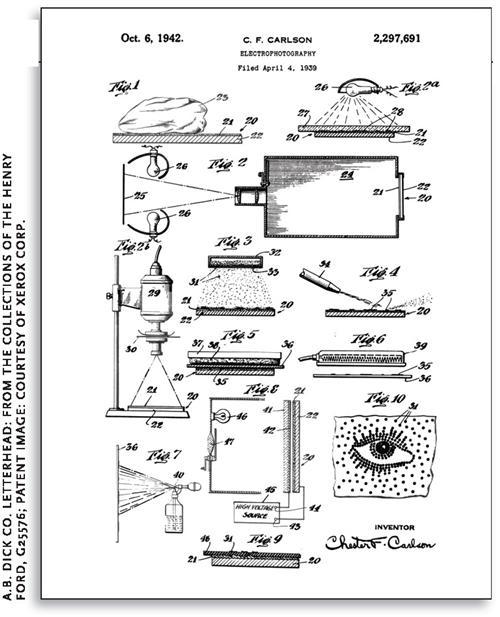

Today, we don’t say, “I need this Rectigraphed,” largely because of an arthritic New York patent attorney: the aforesaid Chester F. Carlson. A prolific inventor when he was’t vetting others’ gizmos, carlson came up with a “trick paper clip,” a shoe-cleaning machine, a rotating bill-board — and what would come to be known as the Xerox machine. Tired of hand-copying documents, Carlson began investigating electrophotography, a principle demonstrated by Bulgarian physicist Georgi Nadjakov. Carlson duplicated Nadjakov’s experiments in his Astoria, Queens, kitchen using a bright light and a zinc plate coated with sulfur. His first photocopy, now in the Smithsonian, reads “10-22-38 Astoria.”

But the world didn’t exactly embrace his better mousetrap. More than 20 companies, including Kodak, RCA, IBM and General Electric, rejected his idea. Finally, in 1944, the Battelle Memorial Institute, a Columbus, Ohio, nonprofit organization, agreed to help develop his photocopier.

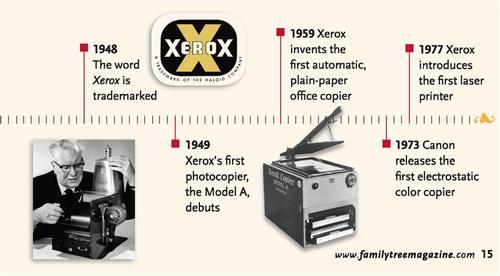

In 1947, Haloid — the small photographic-paper maker that had bought Rectigraph — licensed the technology. Thinking electrophotography lacked marketing pizazz, Haloid hired an Ohio State classical-language professor to help come up with a better name. He suggested xerography, from the Greek for “dry writing.” That became “Xerox,” and the first Xerox photocopier — humbly dubbed, like Henry Ford’s first car, the Model A — was introduced in 1949. A decade later, the Xerox 914 (named after its maximum 9×14-inch copy size), the first automatic, plain-paper copier, revolutionized office work.

“Technically, it did not look like a winner;” recalled Horace Becket, chief engineer for the Xerox 914. “That which we did, a big company could not have afforded to do. We really shot the dice, because it didn’t make any difference.”

Repeat Performers

Visit these museums and Web sites to learn more about the history of makin’ copies.

Bartleby.com: Bartleby the Scrivener

Early Office Museum

George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film

900 East Ave., Rochester, NY 14607, (585) 271-3361, <www.eastmanhouse.org>

The Henry Ford

20900 Oakwood Blvd., Dearborn, MI 48124, (313) 982-6001, <thehenryford.org/collections/acquisitions>

The Museum of Printing History

1324 W. Clay St., Houston, TX 77019, (713) 522-4652 <www.printingmuseum.org>

Xerox Corp.

Before the Copier: a Scrivener’s Job

“At first Bartleby did an extraordinary quantity of writing. As if long famishing for something to copy, he seemed to gorge himself on my documents. There was no pause for digestion. He ran a day and night line, copying by sun-light and by candle-light. I should have been quite delighted with his application, had be been cheerfully industrious. But he wrote on silently, palely, mechanically.

“It is, of course, an indispensable part of a scrivener’s business to verify the accuracy of his copy, word by word. Where there are two or more scriveners in an office, they assist each other in this examination, one reading from the copy, the other holding the original. It is a very dull, wearisome, and lethargic affair. I can readily imagine that to some sanguine temperaments it would be altogether intolerable.”