Forty years ago, when “Mr. McGuire” leaned over to say “one word … just one word” to Dustin Hoffman in the 1967 film The Graduate, that word—plastics—had already come to suggest everything phony and cheap in the modern world. But when “the material of a thousand uses” was invented 100 years ago, plastic promised our ancestors a future as bright and shiny as the newfangled substance itself: As Jeffrey L. Meikle puts it in American Plastic: A Cultural History (Rutgers University Press), plastic “would transform the world from a crude, uncertain place into a stable environment of material abundance and startling artificial beauty.”

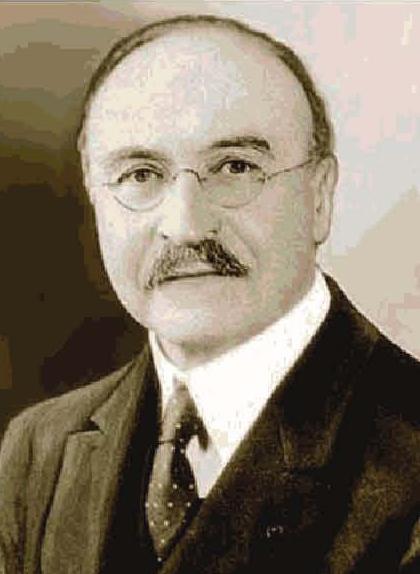

The material that ushered in the “Plastics Age” was Bakelite, the first completely synthetic manmade substance. It was created in 1907 by Leo Baekeland, a New York chemist. Baekeland, born in 1863 in Ghent, Belgium, had become a professor of chemistry by age 26. But he didn’t take to the academic life and in 1890 immigrated to the United States in search of broader horizons. He quickly found them, inventing a photographic paper, Velox, which he sold to Eastman Kodak for the princely sum of $1 million. Though Baekeland could’ve comfortably retired, he kept inventing. He developed a pot like apparatus that could precisely control the heat and pressure applied to volatile chemicals, using it to create a resin that, when cooled, hardened into the shape of its mold and was virtually indestructible. Bakelite was born.

Few materials in history have been so rapidly adopted. Thomas Edison made a Bakelite record in 1912; Western Electric, a telephone receiver in 1914; Eastman Kodak, a camera in 1915. Philips began making Bakelite radios in 1923, and the availability of cheap plastic cases—replacing expensive wood—helped make the radio ubiquitous in American life. Without Bakelite, it’s unlikely the 1930 census would have been the first to enumerate radios in US households, and FDR would have had much smaller audiences for his “fireside chats.” It was the ideal material for Art Deco and a Depression-era yearning for progress and modernity.

In 1939, Baekeland’s company merged with Union Carbide and Carbon Corp. By 1944, when Baekeland died, world production of Bakelite had reached 175,000 tons.

Although Bakelite was the first synthetic plastic, earlier inventors had succeeded in making organic plastics. In 1862, Alexander Parkes unveiled “Parkesine”—the original plastic, derived from cellulose—at the Great International Exhibition in London. A few years later, the booming popularity of billiards led to the slaughter of thousands of elephants for their ivory tusks, and a $10,000 prize for a material that could replace ivory in billiard balls. American John Wesley Hyatt rose to the “artificial ivory” challenge and in 1869 invented celluloid, made from colloidon. The addition of camphor, derived from the laurel tree, solved the problem of colloidon’s brittleness—the billiard balls would otherwise shatter when they collided—and made celluloid the first thermoplastic (“a substance molded under heat and pressure into a shape it retains even after the heat and pressure have been removed,” according to the American Chemistry Council). Seeking manmade silk, Louis Marie Hilaire Bernigaut developed rayon, another cellulose derivative, in 1891.

Other plastic breakthroughs would follow Bakelite and eventually supplant it as the world’s primary plastic. A group led by DuPont chemist Wallace Hume Carothers created nylon—originally “Fiber 66”—in the 1930s. Polyethylene, discovered in 1933, helped America win World War II, serving as an insulating material light enough to put radar on airplanes. After the war, polyethylene grew to become the world’s leading plastic.

Surprisingly, though, it wasn’t until several decades after the invention of Bakelite that we started using the word plastics. Industry began adopting the term with the publication of a trade journal, Plastics, in 1925. The general public didn’t start calling these new miracle materials “plastics” until the mid- to late 1930s, according to Meikle.

From the July 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.