Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

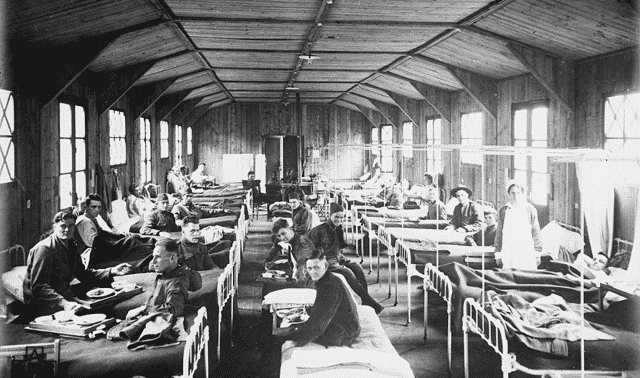

The Flu’s Death Toll

The great flu pandemic of 1918 killed up to 675,000 Americans, 0.65 percent of the nation’s population. Most died in a terrifying span of 16 weeks. Worldwide, death estimates range from 21 million to 100 million.

How the Pandemic Affected Your Ancestors

The deadly virus may have first appeared in Haskell County, Kan., from which newly mustered soldiers spread it to Camp Funston, Kan., in February 1918. The gathering of men from across the country into close quarters galvanized the flu: In the spring of 1918, 24 of the 36 largest army camps suffered outbreak and 30 of the 50 largest US cities—notably, those close to Army bases—also saw outbreaks.

But nobody thought much of it at the time. Then the flu returned with a vengeance in September, striking first in Philadelphia, where it quickly overwhelmed the city’s ability to deal with the dead. Soon, steam shovels were digging mass graves. (Keep this grisly bit of history in mind if you can’t find the burial site of an ancestor who died in late 1918.) Some cities became ghost towns save for municipal workers in masks. In most areas, gathering places from schools to saloons were shuttered and public meeting banned.

If Your Ancestor Died of the Flu

The 1918 flu struck many in the prime of life—half the US dead were between the ages of 16 and 40. So many young people died, according to because of what’s today recognized as a pathological process called Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. A pulmonary expert describes it as “a burn inside the lungs.” Your ancestor’s death certificate likely ascribed the cause to pneumonia, if not to influenza.

The cycle of infection in each locale typically ran from six to eight weeks; then the incidence of flu dropped off sharply. As survivors gained immunity and the killer virus mutated, the pandemic burned itself out. In Philadelphia, where 4,597 people died from the disease in one October week, influenza had all but vanished by Armistice Day less than a month later.

Most death indexes don’t list a cause of death; so you’ll need to get a copy of your ancestor’s death certificate—typically from the county courthouse or the state archives. See when states began requiring death certificates on our Vital Records Chart. Besides gleaning valuable genealogical data, you may get a glimpse of the killer that stalked the world in the fall of 1918.

Other Major US Epidemics

Epidemics raged throughout US history. Early on, an infectious disease outbreak might be confined to a city or two, with ports particularly susceptible due to passengers on arriving ships. Many areas saw the same disease return year after year. But as Americans moved westward and became more mobile, epidemics were more widespread. Indian tribes, lacking the immunity some Europeans had, died in great numbers. These are major US epidemics and their geographic areas of concentration.

Cholera

Cholera is contracted by coming in contact with food or water contaminated by infected human waste. It first appeared in the United States in 1832 as farmers, manufacturers and towns disposed of human, animal and industrial waste in waterways. Outbreaks occurred throughout the nineteenth century. In 1849, an epidemic spread up the Mississippi River, killing 3,000 in New Orleans and 4,500 in St. Louis. An 1854 outbreak in Chicago killed 3,500. In 1866, 50,000 Americans died of cholera.

Smallpox

The HBO miniseries “John Adams” by David McCullough has a memorable scene in which Abigail Adams and her children are vaccinated against smallpox. The doctor takes fluid from pustules on a sick man and puts it into a wound he’s created on the arm of each child and Abigail. Submitting to that was a brave act. Epidemics of the disease continued, with an 1837 Great Plains outbreak supposedly caused by a hand on an American Fur Co. steamboat.

Smallpox entered the British Colonies with the earliest settlers and devastated Indian populations. In 1796, English physician Edward Jenner discovered that immunity to smallpox could result from exposure to cowpox (a milder variety of the disease affecting cattle) and began experimenting with vaccinations. Newport, RI, doctor Benjamin Waterhouse was the first in the Colonies to use Jenner’s inoculation, administering it to his son July 8, 1800. In 1810, Sylvanus Fansher earned about 5 cents a person to vaccinate more than 4,000 people in the City of Providence—the first municipality in the state to support public smallpox vaccination. Successful vaccination campaigns led to the World Health Organization certifying the eradication of smallpox in 1979.

Typhoid fever

As with cholera, contaminated food and water also contributes to typhoid outbreaks. In the 19th century outbreaks were common, especially among individuals who ate raw seafood. 1891, the typhoid death rate was 174 per 100,000 people in Chicago.

Typhoid can be transmitted from a carrier to another person through food handling. The infamous Typhoid Mary, an Irish immigrant identified in 1907 as a known carrier who refused to stop working as a cook is closely associated with dozens of cases and three deaths. She died in 1938 in forced quarantine. Vaccination and antibiotics have made Typhoid rare in developed countries.

Yellow Fever

Health professionals now know that mosquitoes spread yellow fever, and the malady isn’t contagious between humans—not so for earlier generations. The bug killed whole families swiftly and horribly, causing fever, chills, nausea and internal bleeding. A 1793 outbreak struck Phildelphia; New Orleans was hit in 1853; Norfolk, Va. in 1855 and Memphis in 1878. From 1882 to 1889, yellow fever defeated French efforts to build a canal in Panama. The disease causes an estimated 30,000 deaths every year in unvaccinated populations.

Timeline of Major US Epidemics

1721 smallpox (New England)

1770s smallpox (Pacific Northwest)

1772 measles (North America)

1793 to 1798 yellow fever (recurs in Philadelphia)

1832 cholera (New York City, New Orleans and other major cities)

1837 smallpox (Great Plains)

1841 yellow fever (Southern states)

1849 cholera (New York City)

1849 cholera (New Orleans, St. Louis and along the Mississippi River)

1850 influenza (nationwide)

1851 cholera (Great Plains)

1852 yellow fever (nationwide, especially New Orleans)

1853 yellow fever (New Orleans)

1855 yellow fever (nationwide)

1862 smallpox (Pacific Northwest)

1865 to 1873 typhoid, yellow fever, scarlet fever recur (nationwide)

1867 yellow fever (New Orleans)

1878 yellow fever (lower Mississippi River valley)

1916 polio (nationwide)

1918 Spanish influenza (nationwide)

1949 polio (nationwide)

1952 polio (nationwide)