In a 1776 letter, Abigail Adams admonished her husband, John, to “remember the ladies” as the Continental Congress struggled to establish a government. Even though women weren’t allowed to vote on a national level until 1920, many, like Abigail, took an interest in political affairs.

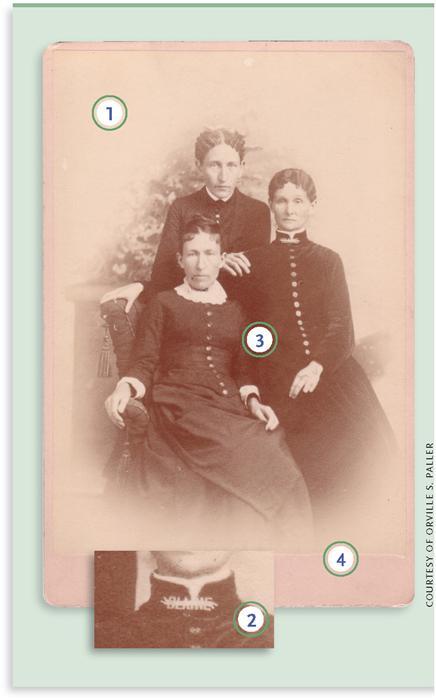

Frances Althea Cuppernell, shown here on the right, didn’t leave writings expressing her views. But as you’ll see, details in this portrait reveal hidden aspects of her political leanings. Her great-great-grandson Orville S. Paller sent this image to me because he’s been unable to crack the identity of the two ladies posing with Cuppernell. Paller wondered if his ancestor’s unique bar pin could hold the answer to this pictorial brick wall. Let’s stack up the facts and find out.

Pinpointing a date

Even before we consider the pin, the women’s outfits provide a time frame. All wear dresses with high necklines and buttons down the bodice. The one in front has a wide lace collar; her hair is up on the crown of her head. Frances and the woman in back both wear center-parted hair with soft waves. These dress styles and hairdos were popular in the mid-1880s.

Cuppernell’s pin in the shape of the word Blaine, though, more-specifically dates the image and gives us a glimpse into this woman’s life. Paller realized the jewelry is a clue, but wasn’t able to identify its significance — Blaine isn’t the name of any branch of his or an in-law’s family.

Research into US history reveals the accessory doesn’t relate to the family, but to Cuppernell’s political leanings. Even when they couldn’t vote, women still supported or opposed political causes.

In this case, the pin shows Cuppernell’s backing for little-known presidential candidate James G. Blaine. The Republican tried to earn his party’s nomination in 1876 and 1880, finally achieving his goal in 1884. Democrat Grover Cleveland challenged him in a tense campaign: Cleveland admitted he’d fathered a child illegitimately; Blaine was accused of being anti-Catholic and accepting bribes.

According to Jordan M. Wright’s Campaigning for President: Memorabilia From the Nation’s Finest Private Collection (Smithsonian, $35), US political memorabilia originated around 1796, when John Adams became president. He’d used paper lanterns to promote his candidacy. Franklin Pierce, elected president in 1852, first used photos on a variety of campaign propaganda, some of it — including aprons, hairpins and jewelry — designed for women. (See examples of campaign propaganda in the New York Times article at <www.nytimes.com/2008/06/28/arts/design/28muse.html>.) Blaine’s campaign made pocketbooks for his female supporters.

The combination of clothing and Cuppernell’s bar pin date this image to the few months in 1884 between Blaine’s acceptance of his party’s nod and his election loss to Cleveland.

Political leanings

Paller was surprised to learn this photo could establish Cuppernell as a Republican. At the time, the Republican party — to which Abraham Lincoln had belonged — was considered the more liberal faction. It’s unknown what influence (if any) Cuppernell’s political values may have had on her husband’s vote, whether she supported women’s suffrage, or why she backed Blaine. But by setting this photo into the context of her life, you get a sense of her as a person.

Born Feb. 8, 1845, in Illinois, Frances Althea (aka Allie) married William Henry Vredenburgh at age 17. Three years later, May 26, 1865, their divorce was finalized. At the time, divorce was granted only in extreme circumstances. Illinois statutes in 1856 define those as bigamy, adultery, desertion for at least two years, cruelty, drunkenness or felony conviction, says Ray Collins, reference librarian at the Illinois State Library.

Cuppernell’s husband had deserted her. In August 1865, she remarried to Albert Marion Swarthout, who remained her spouse until her death in 1891. Paller’s genealogical research and the visual evidence in the photograph suggest she was a woman of strong convictions. Why else wear a piece of political propaganda in an era when a woman’s place was at home caring for her family?

Perhaps her choice to wear political jewelry also reflects her position on women’s issues. In the 1880s, the American Women’s Suffrage Association and the National Women’s Suffrage Association advocated for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote. Interestingly, members of the NWSA also supported easier divorce laws for women — a stance Cuppernell might’ve appreciated — and an end to sex discrimination in employment.

Campaign Strategies

1. History matters. Studying history can help you add context to old photos.

2. Pinned down. Look carefully at jewelry: It might be more than mere ornamentation.

3. Costume check. Clothing and hairstyles can help establish a time frame for an image.

4. Record review. Your genealogy research may add insight to clothing and accessory choices.

From the November 2008 Family Tree Magazine