Photographs have complicated lives. Our ancestors posed for images, then those photographs often ended up scattered among relatives or abandoned. When you’re faced with an unidentified photo, ask extended family members if they’ve seen the image before. Often, another relative owns a captioned duplicate of your mystery image.

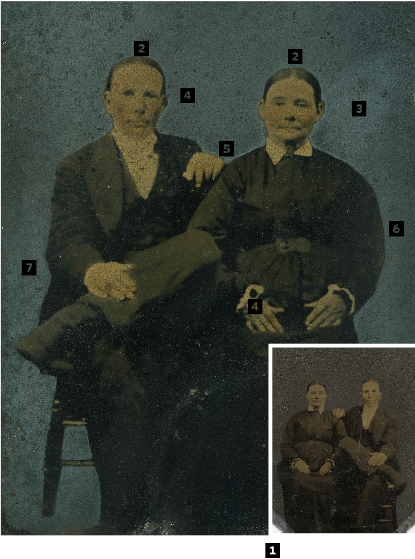

Thomazin’s cousin Jerry Huey received the first tintype from his mother, who got it from her mother. Huey’s grandmother and Thomazin’s grandmother were sisters, the daughters of William Calvin and Catherine Elizabeth (Newman) Dunaway. Huey believes his mother wrote the “Grandma Dunaway’s parents” caption on the back, referring to Catherine’s parents, Wesley (1821-1899) and Elizabeth (Close) Newman (1826-1919).

Another of Thomazin’s cousins, Kenneth Mickelson, had a reversed image of the tintype. But he’s not related to the Newmans—he’s the great-grandson of William Calvin Dunaway’s sister Cordelia. Perhaps Huey’s mother was wrong. Could this image show James William Harvey Dunaway (1829-1880) and his wife, Tracy (Bateman) Dunaway, who would’ve been 40 and 49 in 1869?

Ownership is a key clue. How did two different members of the family end up with the same image? Look for a common ancestor—in this case, someone in the Dunaway family.

Given the time frame of the image and Mickelson’s lack of connection to the Newmans, this probably isn’t them.

Why the reversed image? Early tintypes were typically developed as reversed images. Later, cameras were adapted to “fix” the reversal. It’s possible that these photos are copies of another photo. Without the original photograph, though, it’s impossible to tell which one shows the actual pose. View another photo from Thomazin’s family on the Photo Detective blog <blog.familytreemagazine.com/photodetectiveblog>.

The man wears his hair heavily oiled. His wife’s simply styled hair is pulled back severely behind her ears. Both hairstyles are atypical for the late 1860s, when men’s hair was generally longer and women’s fuller. It’s common, though, to see a wide variety of hairstyles in every decade.

Unfortunately, the lack of detail in these tintypes makes it difficult to determine the ages of the man and woman based on their appearance.

The photography studio sought to add life to this picture by giving the subjects blue eyes and gold wedding rings—common touches to tintypes.

The woman’s loose tie at the neckline fits the late 1860s. Her husband’s wide-lapel jacket also is appropriate for that time frame.

The bodice of the woman’s dress is in the basque style, which extended over the hips and had rectangles of fabric visible over the skirt. It derives from French dress native to the Basque region. Belted waistlines and basque bodices were commonly found in women’s attire in the late 1860s.

By painting the background of the image, the photographer directed attention to the subjects. You can learn more from Forgotten Marriage: The Painted Tintype and the Decorative Frame 1860-1910 by Stanley B. Burns (The Burns Collection).

You’ll find more help solving family photo mysteries in Uncovering Your Ancestry Through Family Photographs, 2nd edition, by Maureen A. Taylor (Family Tree Books).

From the September 2010 Family Tree Magazine