Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

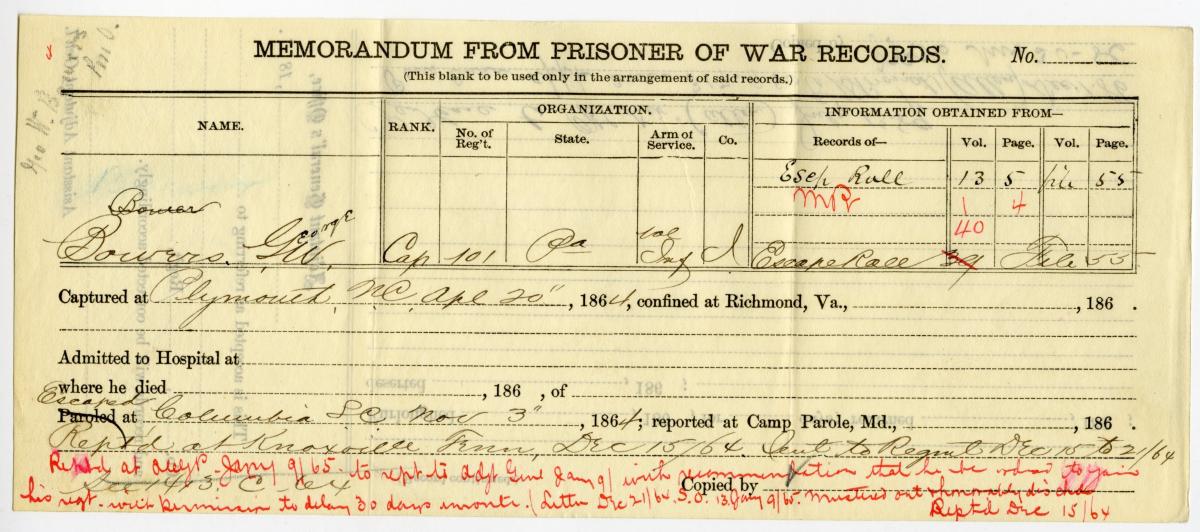

Military records reveal a tremendous amount of detail about your relatives—and you may even find documents about those who didn’t serve. Such is the case with WWI draft cards.

The Selective Service Act of May 18, 1917, defined five functions leading to induction of men into the US Army or the states’ National Guards: registration, selection, classification, induction and entrainment of inductees to training and mobilization camps.

Every eligible male had to go to his local draft board office to submit a registration card and be interviewed by an official. The official filled out the card and the registrant signed it. Four registration “waves” targeted men of specific ages:

- First Registration: June 5, 1917; men age 21 to 31

- Second Registration: June 5, 1918; men who’d turned 21 since June 5, 1917

- Supplemental Second Registration: Aug. 24, 1918; men who’d turned 21 since June 5, 1918

- Third Registration: Sept. 12, 1918; men age 18 to 20 and 31 to 45 who hadn’t previously registered

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) facility in Morrow, Ga., has the original cards. They’re on microfilm at many NARA branches and the FamilySearch Library. They’re digitized on subscription site Ancestry.com (ask if your library has the free Ancestry Library Edition).

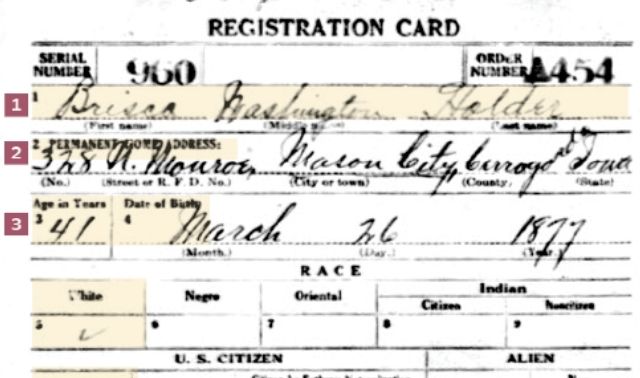

The military drafted registrants by lottery and inducted those deemed physically acceptable. So the existence of a draft registration card is no guarantee your ancestor served—but as my great-uncle’s card shows, it does guarantee a windfall of genealogical details.

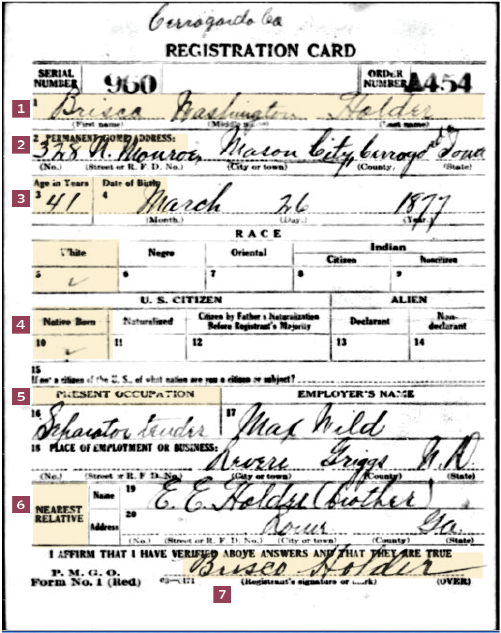

1. The registrant was required to enter his full name (no initials) and was assigned a unique number—making it easier for you to find his military records.

2. Use the registrant’s permanent address to locate other records where he lived. Can’t find him in the 1910 and 1920 censuses? Determine the enumeration district for each census at Stephen P. Morse’s One-Step site and browse the records.

3. The age and birth date tell you how old the registrant should be in other records you’re looking for.

4. If the person was naturalized, look for citizenship papers. Some are available through Ancestry.com and Fold3, or try the US Citizenship and Immigration Service Genealogy Program. A registrant designated “alien” might have filed for naturalization under a law expediting the process for servicemen.

5. Research the employer in city directories and newspapers for insight into your relative’s life. You also might find information in special agricultural or manufacturing censuses.

6. Registrants in 1918 had to name their nearest relative and give that person’s address. A married man usually listed his wife; an unmarried man might have listed his parents, a sibling or another relative—opening up avenues for collateral research. The card often tells the relationship.

7. Your ancestor’s signature indicates literacy and his approval of the information’s accuracy. An X indicates illiteracy and should lead you to question the accuracy of details and spellings.

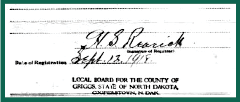

The registrar’s signature and date help confirm which registration day the record was created. You may find that, as in this case, the registration was taken by one draft board and forwarded to another for processing. My great-uncle registered in Cooperstown, N.D., where he worked, but he lived across the state line in Mason City, Iowa.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the January 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: June 2025