Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Who could ever forget Gerald O’Hara’s famous words to his spirited daughter in Gone with the Wind? You can probably hear his Irish brogue resonating in your head:

“Do you mean to tell me, Katie Scarlett O’Hara, that Tara, that land doesn’t mean anything to you? Why, land is the only thing in the world worth workin’ for, worth fightin for, worth dyin’ for, because it’s the only thing that lasts.”

Like Gerald, our ancestors coveted land — to them it meant stability, ownership and family tradition. Many left their homes in Europe, where their roots had been planted for centuries, just for the opportunity to buy and own land in the United States. Others abandoned comfortable homes and trekked across the vast, uncharted American plains and deserts to fulfill their yearning to become landowners. The desire for land was so overwhelming that settlers uprooted, relocated and even massacred the prior inhabitants — American Indians — in order to claim a piece of property. Land was not only worth dying for: It was worth killing for, too.

ADVERTISEMENT

The story of your ancestors’ land ownership might not be as romantic or inspiring as Gone With the Wind. But odds are good your kin owned land at some point. In fact, you may find some of your forebears bought and sold land more frequently than they bathed. And those sales generated paperwork: deeds, patents and other documents that, on the surface, might not exactly look as glamorous as Scarlett’s hoop skirts. But if you dig deeper, you’ll discover land records hold much more than unfamiliar legal jargon and dry land descriptions. You don’t need a law degree to figure them out, either. Our primer will cover all the genealogical real estate.

From headrights to homesteads

How do you begin researching your clan’s Tara? Depending on how and when the property was transferred, you’ll stake a claim to different types of documents. So let’s start by surveying the landscape of land distribution in the United States.

When the British crown laid claim to the New World, it granted land to the proprietors of Plymouth Colony and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who in turn granted parcels to settlers. You can find many of those early grants published in David Pulsifer and Nathaniel B. Shurtleff’s 12-volume Records of the Colony of New Plymouth in New England — volume 12 contains deeds from 1621 to 1651 — and Shurtleff’s five-volume Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England. Genealogical libraries, including the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL), will have copies.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many Colonial immigrants had their passage paid in exchange for an indenture: a period of servitude averaging seven years. A sponsor who paid these newcomers’ fares could claim a “headright” — generally 50 acres of uncultivated land for every head he transported, including his own and his family’s. Virginia used the headright system from 1619 to 1705; Maryland and the Carolinas retained it slightly longer.

Headrights typically list the names of the claimants and the people they transported, as well as the acreage, county and land description. For example, this abstracted headright claim appears in the first volume of Nell Marion Nugent’s Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants (Library of Virginia):

Christopher Robinson & John Sturdevant, 600 acs. Henrico Co., 23 Feby. 1652, p. 172. Upon the heads of the Eastern run of Swift Cr. Known by the name of Mr. Hatchers run &c., towards the Ashen Swamp, etc. Trans. of 12 pers: Wm. Hayward, Elianor his wife, John Kendall, James Hewes, James Sturdey, Robt. Kinge, Edward Bayle, Tho. Edwards, Hester Paulwin. 2 rights by assignmt. From Mihill Masters.

Other helpful headright sources are Gust Skordas’ The Early Settlers of Maryland: An Index to Names of Immigrants Compiled from Records of Land Patents, 1633-1680 (Genealogical Publishing Co.) and A.S. Salley Jr.’s Warrants for Land in South Carolina, 1672-1711 (University of South Carolina Press). Both are out of print, but available at genealogical libraries.

In 1776, Congress authorized bounty-land warrants to entice men to serve in the Revolutionary War. These warrants entitled the soldier to free land upon his discharge — the grant ranged from 50 to 1,000 acres, depending upon his rank. But many soldiers sold their bounty land to speculators, without ever settling it. Later legislation granted bounty land for wartime service through 1856.

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) has microfilmed bounty-land application files, as well as many “surrendered” warrants. There are indexes to these records available at Fold3 and FamilySearch. You can then order copies of the original files from NARA. You’ll find some records online: If your library subscribes to Heritage Quest Online, you can search and view images of Revolutionary War applications and at Ancestry.com you can search the U.S., War Bounty Land Warrants, 1789-1858 database. A small database of digitized bounty-land applications can also be searched at NARA.

You also should check published abstracts, such as Virgil D. White’s four-volume Genealogical Abstracts of Revolutionary War Pension Files and three-volume Index to War of 1812 Pension Files (both are out of print, though you can get them from the FHL). Note that the latter doesn’t include the numerous unindexed War of 1812 bounty-land files held by NARA. Some states also granted land to their veterans — see Lloyd de Witt Bockstruck’s Revolutionary War Bounty Land Grants Awarded by State Governments (Genealogical Publishing Co., out of print).

The federal government didn’t limit its land giveaways to soldiers. To encourage westward settlement, it passed several 19th-century land acts, most notably the Homestead Act of 1862. This legislation granted 160 acres of federal government land to anyone who would settle and make improvements to it for five years. Even recent immigrants could participate if they’d filed a declaration of intention for US citizenship. By 1900, 600,000 Americans — who embraced Gerald O’Hara’s sentiment that land was “worth workin’ for” — had claimed 80 million acres.

If your ancestors followed this path to free land, they would’ve generated a homestead entry file with the paperwork created over the course of the claim, including the application and the final “patent” (which documents the transfer of land from the government to an individual owner). Immigrants’ homestead files contain copies of their naturalization papers: To secure their patents, they had to prove they’d become citizens by the end of the five-year term.

Not all homesteaders received patents — in fact, more than half of the 2 million total entries were cancelled because the applicants didn’t complete the requirements or make all the deadlines. A file with the application and reason for cancellation should still exist, though. You can get homestead records from several places: NARA, the appropriate state’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) office, and the county courthouse.

Keep in mind that even though oral history interviews, letters, and diaries may reference a family “homestead,” that doesn’t necessarily mean your ancestors acquired their lands under the Homestead Act. Referring to any property as a homestead was common terminology for that time period. If your kin got land from the US government through a sale or other giveaway, similar documentation — including tract-book entries, land entry case files and patents — should exist.

Perhaps the first place you should look is the BLM’s General Land Office Records Web site: It serves up images of 2 million federal land patents issued between 1820 and 1908 in Eastern public-land states. You’ll find patent information and legal land descriptions for other public-land states, too — that is, states where the US government was the initial landowner. The site doesn’t cover state-land states — the 13 former Colonies plus Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont and West Virginia — because their state governments retained property rights after joining the Union. You can download a PDF of most patents or you can order certified copies. The BLM GLO website also has a very cool tool to help you map out your ancestor’s property.

Offline, you can use tract books — copies are held by NARA, BLM offices, state archives and historical societies, and even county courthouses — to look up the legal land description. With those details, you can order the full land-entry case file from NARA.

Prior to the Homestead Act, federal, state and territorial governments passed similar land-giveaway laws, called donation acts, to encourage settlement in Arkansas, Florida, Oregon, Washington and New Mexico. You can find donation files at NARA, or check state-level repositories. The Genealogical Forum of Oregon has an an Index to Oregon Donation Land Claims and then you can contact them for copies of the relevant pages.

Taken for granted

What if your progenitors purchased their property from another person, rather than the government? Deeds recorded the sale of land from one individual to another. They’re the most voluminous type of land record, and they’re widely available to genealogists. For the most part, you can find deeds dating from the beginning of a town or county’s settlement. Even when courthouses burned, many were rerecorded — after all, no one wanted land ownership left open to dispute.

You’ll find deeds in county courthouses, except in New England states, where they’re typically in town halls. Clerks generally recorded copies in huge ledger books, including an index with each volume. (Note that deed books contain duplicates — the original deeds went to the landowners.)

You don’t necessarily have to write or travel to find your family’s deeds, though. The FHL microfilmed many deeds, and many are available to view digitally at FamilySearch.org. To find deeds in the FamilySearch catalog, do a place search for the state and county, then look under the heading Land and Property. Sometimes only the indexes (not the actual records) are on microfilm. In that case, you’ll have all the pertinent information — namely, the volume and page number — to request the deed from the courthouse. Check the courthouse’s website for details on how to order and if there is a fee for copies.

Deed books usually have two types of indexes: one for grantors (the people selling property) and one for grantees (the buyers or recipients). In some places, they’re referred to as direct (for grantors) and indirect (for grantees) indexes. Transactions with multiple buyers or sellers might be indexed under the first person listed in the document followed by et al., meaning “and others.” Or you may see a man’s name plus et ux., which stands for “and wife.” If a deceased property owner’s executor is making the transaction, the index might list the executor’s name. Like other records, deed indexes contain errors and omissions — so take this into consideration if you don’t find a land entry for one of your ancestors. You may have to go page by page through the deed book.

More than measurements

When I was just a baby genealogist, I remember my colleagues raving about land records. I thought, “What’s the big deal? So you know the legal land description.” Then I discovered what all the hype was about. Land records might give you family relationships. Aha! Look at all the genealogical details my colleague Marcia Wyett found in this Nicholas County, Ky., deed:

Know all men by these presents that we Henry McClintock and Catherine McClintock wife of the said Henry (which Catherine was formerly Catherine Johnson and daughter of Ann Johnson, who is now deceased and who was one of the heirs at law of John Harding deed, who died in Nicholas County in the state of Kentucky about two years ago more or less) and Mary Harding widow of Charles Harding deceased which Charles Harding was the son and one of the heirs at law of the aforesaid John Harding of Kentucky … And I the said Mary Harding being the natural guardian of my two infant children, Henry Harding and Jane Harding, who are the children and heirs at law of my said deed, husband…

Even though it took me awhile to get excited about a legal land description, eventually I did because from that information, I could actually walk on the property where my ancestors lived — and sometimes discover their house was still standing.

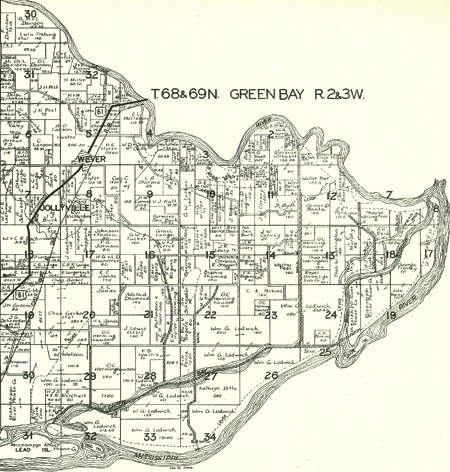

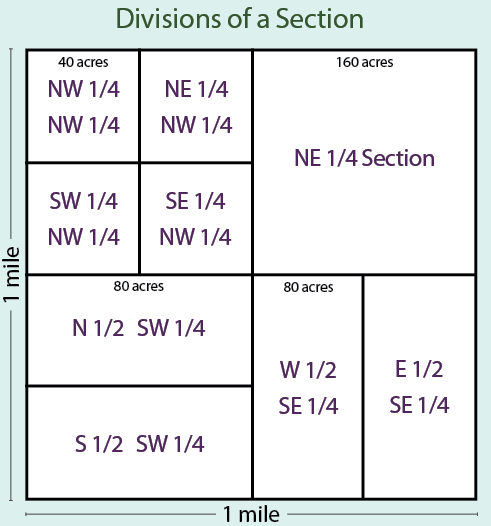

Legal land descriptions follow two surveying methods. The metes and bounds system uses natural and artificial landmarks and adjacent property: “beginning at a white oak … bounded on the east by the property that borders William Thomas.” The state-land states followed this method. The rest (public-land states) employed the rectangular survey system, which divides land into townships and sections: “the west half of the northeast quarter of section 15, township 3 south, range 4 east” (see below for an explanation of this scheme).

With these land descriptions, you can plot the precise location of your ancestor’s property. If you’d rather not pull out your graph paper and protractor, there is software that can help, like DeedMapper. For public-land states, check out Arphax Publishing Co.’s Family Maps books. This series maps millions of federal land patents across much of the United States. In the deluxe editions, you’ll find mapped homesteads with the owners’ names, roads, waterways, towns, cemeteries and railroads. Each volume covers one county. (If you don’t see your ancestral county, check their subscription website HistoryGeo.com) These books also are great for seeing at a glance who your ancestors’ neighbors were — a real boon, since your kin’s relatives and friends often lived nearby and migrated with them.

Deed books often contain more than mere land transactions: You might find mortgages, gifts of transfer, powers of attorney, prenuptial agreements, marriage property settlements, and bills of sale for slaves and other items. Among one volume of old deeds, I found a purchase agreement for a piano.

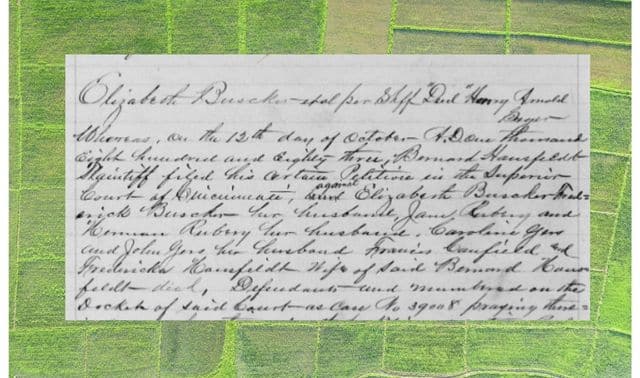

You also might find clues to family relationships. For example, be on the lookout for unusually low-priced sales — if someone sold property to another person for a few dollars or even nonmonetary consideration (such as “love and affection”), the sellers might be relatives. Consider this 1849 deed, in which Isaac Baker and his wife Rachel sold Elizabeth A. Snyder 2 acres of land for $1:

[land in] the town of Winchester [Frederick County, Va.] containing two acres more or less being part of a larger lot owned by John Baker dec’d which larger lot is bounded as follows on the North by the lands of Geo W Baker on the West by the lands of the late Hannah Dunbar on the South by the road leading from Winchester to Berryville and on the East by the lands of the said John Baker dec’d the portion hereby conveyed was conveyed by said John Baker to said Isaac Baker by deed dated April 29 1840 and duly recorded in said county and mentioned by said John Baker in his will now of record in said county, at the West end of said larger lot…

Based on the description — the land was part of John Baker’s larger lot, which was adjacent to George W. Baker’s property and contained land that John willed to Isaac — chances are pretty good Elizabeth A. Snyder’s maiden name was Baker.

Women’s rights

You may notice that when a man bought property, the land record rarely named (or even mentioned) his wife. But when a man sold land, you might find at least his wife’s first name with the release of her dower rights. (This isn’t to be confused with her dowry, which is property she brought to a marriage.) A woman’s right of dower entitled her to a one-third life interest in her husband’s property upon widowhood. A “life interest” meant she’d own the land for as long as she lived, then it would pass back to her husband’s heirs — this ensured the land wouldn’t go to the children of the wife’s next husband. (By the way, deeds weren’t always witnessed by one of the wife’s relatives in order to protect her dower. Witnesses could be relatives of either party.)

Virginia and Maryland established dower rights as early as the 1670s; South Carolina didn’t enact a statute regarding dower until 1715. The Northern colonies were more lax about dower acknowledgments. Connecticut didn’t pass any laws regarding women and property rights until 1723; Pennsylvania waited until 1770, and New York didn’t follow until 1771. You’ll usually find a dower release, such as this one, at the end of a deed:

Personally appeared before the subscriber, an acting Justice of the Peace, in and for said county, Adam Losh and Ann his wife acknowledged the signing and sealing of the foregoing deed … The said Ann Losh being examined separate and apart from her said husband, Adam Losh, and the contents of this deed made known to her by me, she acknowledged she executed the same freely without fear or coercion of her said husband.

On occasion, a wife might’ve refused to release her dower, it was inadvertently overlooked, or the release didn’t happen right away — as with Malissa Hamilton of Macon County, Mo., who didn’t release her dower until three years after her husband sold a parcel of land to Stephan Scott May 4, 1840. Sometimes the issue didn’t arise until a clear title was needed. But if a woman failed to release her dower, she could still make a claim to the property after her husband died.

Dower rights and deeds didn’t play a role in Scarlett O’Hara’s story. But by the saga’s end, she felt the same connection to land that her father did. Is your family’s home site calling you? Start digging up your ancestors’ land records — like Scarlett, you can declare, “Home. I’ll go home.”

Survey Says…

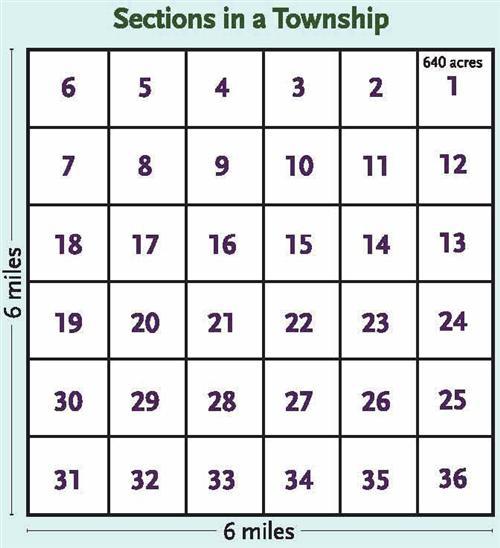

Public-land states divvied up parcels of property according to the rectangular survey system. Use this crib sheet to keep your sections straight.

The principal meridian — an imaginary north-south line — serves as the starting point for surveying a 24×24-mile tract. A tract is divided into 16 townships; every township (23,040 acres) contains 36 sections, each 1 square mile (640 acres).

A section could be split into halves, quarters or otherwise. The descriptions of those subdivisions (such as “the north half of the southwest quarter,” or N½ SW¼ for short) are called “aliquot parts.”

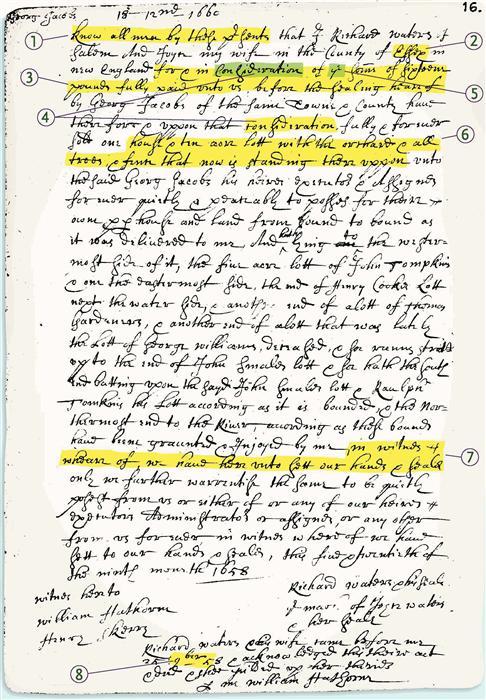

Dissecting Deeds Finding a deed isn’t your only obstacle: Your next hurdle is actually reading it. Aside from the fact the clerk clearly wasn’t hired for his penmanship (or spelling, for that matter), you’ll have to untangle the unfamiliar lingo of old-fashioned legalese. But most deeds are fairly formulaic, so learning their anatomy will help you decipher them — as you can see from this 1658 Essex, Mass., record.

- Grand opening. Most deeds start with the same language: “Know all men by these presents …” as shown here, or “This Indenture made the nineteenth day of May In the Year of our Lord God One thousand Seven hundred and Thirty five.” Try to make out tough passages by comparing these letters with others in the deed.

- Shady characters. Archaic handwriting throws you many curves: An e may be written backward so it resembles an 0, or an s might look like an f — in this deed, for example, Essex could be mistaken for Effoy. Capital letters often look similar: I and J, L and S, L and T, M and N, T and F, U and V. Again, compare characters to words you’ve already deciphered.

- Quick payoffs. You’ll usually find payment details right after the parties’ names. This deed’s phrasing — “for and in consideration of the sum of 16 pounds fully paid unto us, before the sealing hereof” — is common.

- Legal ease. Here, you could tell from the context that consideration means payment. Stumbling over terms such as hereditaments and appurtenances} Read published deed transcriptions from the same time period to get a feel for the jargon.

- Thorny devils. Don’t get stuck on thorns — superscript letters used to abbreviate words that begin a th sound; for example, yt for that or, as in this deed, ye for the.

- Property lines. Look for the land description in the “guts” of the deed. This transaction involves a “house and ten acre lot with the orchard and all the trees, and farm that is now standing thereuppon,” bounded on the west by John Tompkins’ five-acre lot; on the east by the properties of John Tompkins, George Williams and Thomas Gardener; to the south by John Smale’s and Raulph Tompkins’ lots; and to the north by “the Rivers.” The land description also might explain how the seller acquired it.

- End game. Deeds close with more flowery legalese — such as “in witness whereof we have hereunto sett our hands and sealed” here — along with signatures of grantors, grantees and witnesses, and the date (if it wasn’t at the beginning).

- Short-term outlook. Watch for common abbreviations: sd for said, dec’d for deceased, Junr for junior, Jas for James, &c for and etcetera, and (as shown here) 9ber for September.

For additional handwriting help, consult E. Kay Kirkham’s The Handwriting of American Records for a Period of 300 Years (Everton Publishers, out of print), Harriet Stryker-Rodda’s Understanding Colonial Handwriting (Genealogical Publishing Co., $7).

Toolkit

Web sites

- Analyzing Deeds for Useful Clues

- Bureau of Land Management: State Links

- Cyndi’s List Land Records

- Legal Terms in Land Records

- Researching in the Land Entry Files of the General Land Office

- Those Elusive Early Americans: Public Lands and Claims in the American State Papers, 1789-1837

- Understanding Legal Land Descriptions

Books

- Courthouse Research for Family Historians by Christine Rose (CR Publications)

- Family Maps series by Gregory A. Boyd (Arphax Publishing Co.)

- The Genealogist’s Companion & Sourcebook, 2nd edition, by Emily Anne Croom (Betterway Books)

- Land and Property Research in the United States by E. Wade Hone (Ancestry)

- Locating Your Roots: Discover Your Ancestors Using Land Records by Patricia Law Hatcher (Betterway Books)

Organizations

- Bureau of Land Management Eastern States Office, 7450 Boston Blvd., Springfield, VA 22153, (703) 440-1600

- National Archives and Records Administration 700 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20408, (866) 272-6272

A version of this article appeared in the August 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT