Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

It’s probably a bit childish, but I can’t help it. Whenever someone brags to me that she’s a Mayflower descendant, my nose goes a little higher In the air when I respond,“My ancestor arrived 13 years earlier. In 1607, to be exact. To Jamestown.” Maybe it’s because I feel outnumbered – the Jamestowne Society <www.jamestowne.org> has 3,660 current members and 6,678 since its 1936 founding, compared to the General Society of Mayflower Descendants’ <www.mayflowersclciety.com> 27,000 members and 75,000 accepted lineages.

Why the disparity? Whereas the Mayflower colonists consisted of family groups, the first ships to Jamestown carried all men. Not until more than a year later did wives and children travel with colonists to join the original settlers – that is, those who survived. Some historians estimate Jamestown had an 80 percent mortality rate from 1607 to 1625.

Today, as we celebrate the 400th anniversary of America’s first permanent English settlement, interest in Jamestown genealogy is greater than ever. How do you find out If you descend from the select few? Use our guide to uncover your Jamestown connection.

ADVERTISEMENT

Once upon a time, 400 years ago …

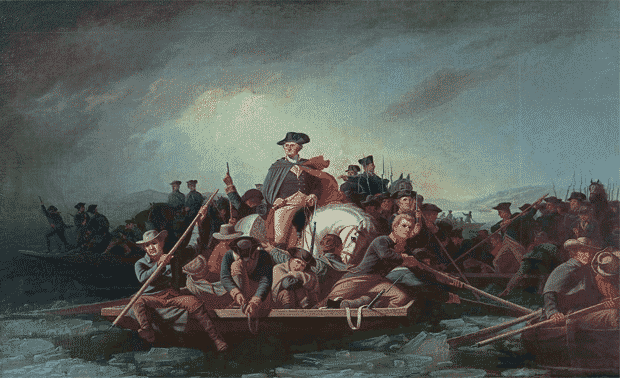

For those of you who (like me) nodded off during high school history class, let’s begin by recapping the history of Jamestown. A little more than 400 years ago, European countries were looking for new land so they could establish colonies. The Spanish had done so in 1565 at St. Augustine in what’s now northern Florida, and the English tried it in 1585 when Sir Walter Raleigh’s fleet of seven vessels carrying 108 men landed on Roanoke Island, near the coast of present-day North Carolina. The Roanoke colonists eventually went back to England. Two years later; another group headed by John White landed there with 150 men, women and children. White returned to England to get more supplies, but the war between Spain and England kept him from going back until 1590. By then, the settlers had disappeared, and Roanoke went down in history as the Lost Colony.

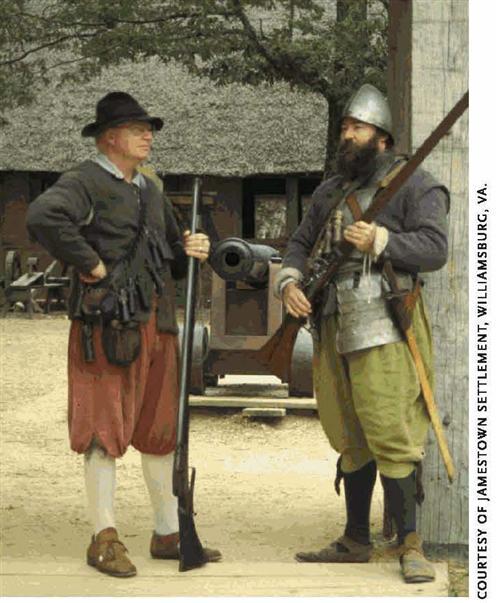

In 1606, King James I granted a charter to the Virginia Company of London, a group of entrepreneurs, to make another attempt at colonization. That December, 105 men embarked on the voyage, traveling on three ships: the Susan Constant, the Godspeed and the Discovery. They landed at Jamestown Island May 14, 1607.

ADVERTISEMENT

Along with the colonists, the convoy carried a sealed box, which was to be opened within 24 hours of arrival in Virginia. Inside, the Virginia Company gave detailed instructions and named who the settlement’s leaders would be. Seven men were to govern the colony, perhaps the most memorable being Capt. John Smith.

Although the Virginia Company told the colonists to “have great care not to offend the naturals” (natives), the newcomers came under attack from the Algonquian Indians, so they built a fort. Fighting with Indians was on-again, off-again, but the Powhatan tribe helped keep the settlers alive by trading food for copper and iron implements. While the settlers might’ve been equipped to deal with their human enemies, they had little defense against famine and disease.

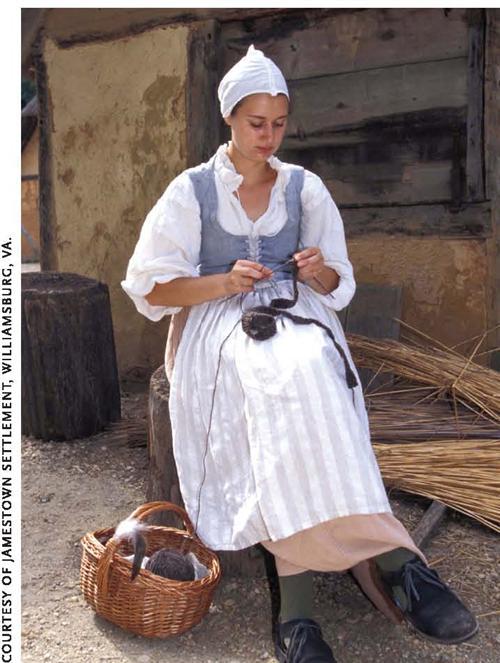

In January 1608, 100 new colonists – toting supplies – arrived to find only 38 survivors. That fall, the second supply ship brought more passengers, including the first two women, “Mistresse Forrest” and Anne Burras, her maid. By May 1610, after another winter; 37 colonists had left by boat and only 60 remained. Just when they were about to give up and return to England, another ship with more settlers and provisions reached them.

Though their suffering continued, the newcomers experienced a few years of peace and prosperity following the April 5, 1614, wedding of John Rolfe to Pocahontas, the favored daughter of the Algonquian chief Powhatan. The colony managed to survive – and you could be one of those hardy colonists’ descendants.

First contact

Whatever genealogical connection you’re trying to prove, it always starts with you. That old adage of starting with yourself and working backward holds true for Jamestown roots, too. Thoroughly research each generation to be sure it connects back to the next one. Ask yourself for each child: “How do I know this is the child of so-and-so? What proof do I have?” You don’t want to accidentally trace the wrong lineage.

Talk to relatives, too. Find out if there are any family stories of Jamestown ancestry. Did Great-aunt Matilda join the Jamestowne Society? If so, contact the group to see if you can get a copy of the paperwork she submitted to become a member.

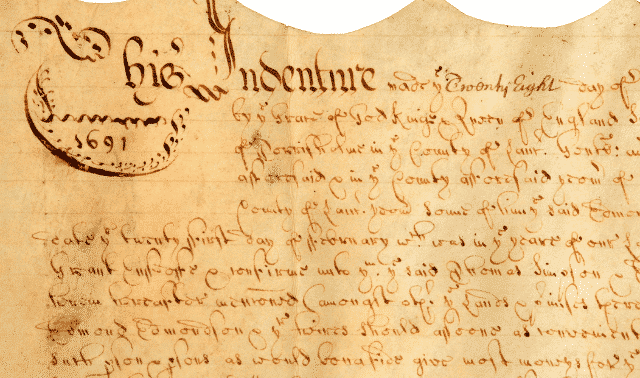

Next, look for original records – censuses, vital records and so forth – in county courthouses or on microfilm at libraries, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov> or the Family History Library (FHL) <www.famllysearch.org>. Remember: The further back you get your lineage (especially beyond 1850, when federal censuses first named every member of a household), it pays off to intensify your sleuthing into documents such as deeds, wills, court records and tax lists.

A good guide to help you with Old Dominion State research is Virginia Genealogy: Sources & Resources by Carol McGinnis (Genealogical Publishing Co.). To find journal articles that may contain information about your Virginia ancestors, check Earl Gregg Swem’s two-volume Virginia Historical Index (Genealogical Publishing Co.). Commonly known as“Swem’s Index,” it’s available in many genealogical libraries.

The Jamestown connection

Your goal, of course, is to link your lineage to a Jamestown settler. You’ll find three lists of them at <www.apva.org/hlstory/list.html>: the Original Settlers, who arrived on one of the three initial ships May 14, 1607; the First Supply, which followed in January 1608; and the Second Supply, which came in October 1608.

Don’t be too quick to claim a connection – just because the same name or surname appears in your family tree, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re related to a Jamestown settler. You’ll have to prove a relationship with thorough research.

Luckily, Jamestown lineages are well-documented: Many colonists’ descents through several generations have been published in print and online, and you can use these sources as jumping-off points. Perhaps the best reference to date is John Frederick Dorman’s three-volume Adventurers of Purse and Person, Virginia, 1607-1624/5 (Genealogical Publishing Co.). These books establish six-generation descents of about 150 people who’ve been identified as either settlers who came between 1607 and 1625 (“adventurers of person”), or Virginia Company of London stockholders who came to the colony during that period or whose descendants did (“adventurers of purse”). For more biographical information, see Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers, 1607-1635: A Biographical Dictionary by Martha W. McCartney (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

When you’re searching for Jamestown colonists and their descendants online, remember that not everything you find is accurate. Look for well-documented genealogies that cite original and respected sources – and steer away from secondary, unverified compilations such as “World Family Tree” or “Jennie’s Genealogy.” These types of sources have such high rates of inaccuracy that the Jamestowne Society won’t accept them as proof of an applicant’s ancestry.

Pocahontas’ progeny

If you have designs on discovering you’re a descendant of Pocahontas, you need to know two things: Contrary to her Disney character, she wasn’t a hot babe “with a Barbie-doll figure” who dressed in “a deerskin from Victoria’s Secret,” explains David A. Price in Love and Hate in Jamestown: John Smith, Pocahontas, and the Heart of a New Nation (Alfred A. Knopf). And she and Smith were never romantically involved, although she did save Smith’s life when he was captured by Opechancanough.

Pocahontas – also known as Matoaka – did marry a Jamestown Englishman, however. She and husband John Rolfe had one known child, Thomas Rolfe, who was born in 1615. Pocahontas died the following year after the three went to England.

Today, more than 100,000 people can claim descent from the Indian princess, says proven Pocahontas descendant David Morenus. If family stories say you might be among them, Morenus recommends you consult two sources compiled by Stuart E. Brown Jr., Lorraine F. Myers and Eileen M. Chappel: Pocahontas’ Descendants (Genealogical Publishing Co.) and Pocahontas’ Descendants: A Revision, Enlargement and Extension of the List (Genealogical Publishing Co.). Check Brown and Myers’ Fourth and Fifth Corrections and Additions to Pocahontas’ Descendants (Genealogical Publishing Co.), too, and see Morenus’ Web site, Pocahontas Descendants <pocahontas.morenus.org/poca_gen.html>, for a chart of some of her descendants.

Red, white and blue Bollings

Pocahontas’s son, Thomas Rolfe, and his wife, Jane Poythress, had only one child, a daughter named Jane. Jane Rolfe married Col. Robert Bolling, and the Bollings were more prolific – so much so that Bolling descendants have been dubbed “red,” for those who descend from Pocahontas; “white,” for those who descend from Col. Robert Bolling and his second wife, Anne Stitch; and “blue” for those Bollings who have appeared “out of the blue” and don’t actually descend from Robert Bolling or (as most claim) his son Col. John Bolling.

Of the 12 “blue” Bollings – whom many people claim as ancestors and thus that they’re Pocahontas descendants – a Benjamin Bolling (1734 to about 1832) deserves special attention. He had, by most accounts, eight children, so he has numerous descendants. But Morenus says DNA tests have ruled Benjamin out as a Pocahontas descendant, and claims of descent through him have been rejected by the Princess Pocahontas Foundation <www.pocahontasfoundation.org>.

Morenus’s site contains a discussion of the Bolling genealogy; you’ll also want to visit the Bolling Family Association Web site <www.bolling.net> for information. To participate in the organization’s DNA study or see the results of the 100-plus men who’ve already been tested, go to <www.bolling.net/bfa_dna_participants.htm>.

Alas, we can’t our ancestors. It was the luck of the draw that I can lay claim to a Jamestown settler through my mother’s paternal ancestry. And given the mortality rate of those original immigrants, I do feel pretty lucky. Otherwise, I might not be here to celebrate the 400th anniversary of my ancestor’s arrival in Jamestown – 13 years before those Mayflower passengers finally got here.

ADVERTISEMENT