In This Article

Birth Details

Maiden Names

Parental Exceptions

Other Family Members

Occupations

Social Security Numbers

Race

Religion

Places of Residence

Military Service

Other Sources

Marital Status

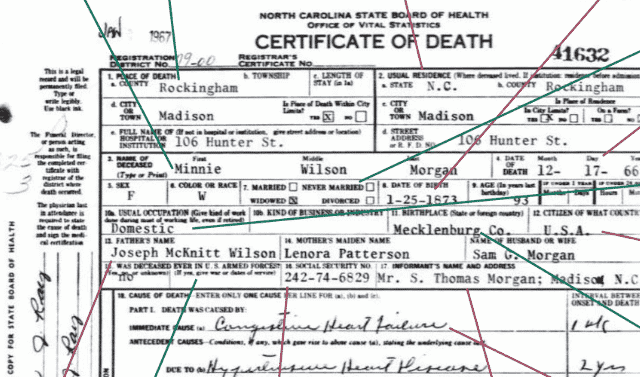

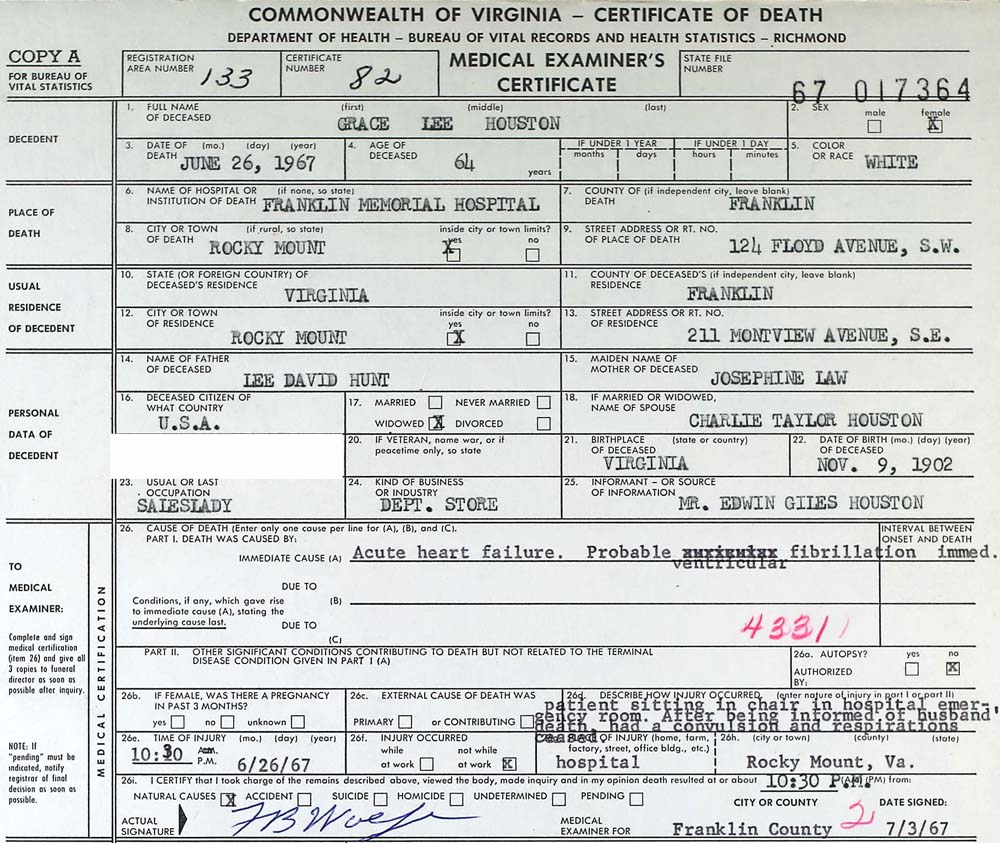

Unusual Causes of Death

Places of Burial

Putting Clues Together in Vital Records

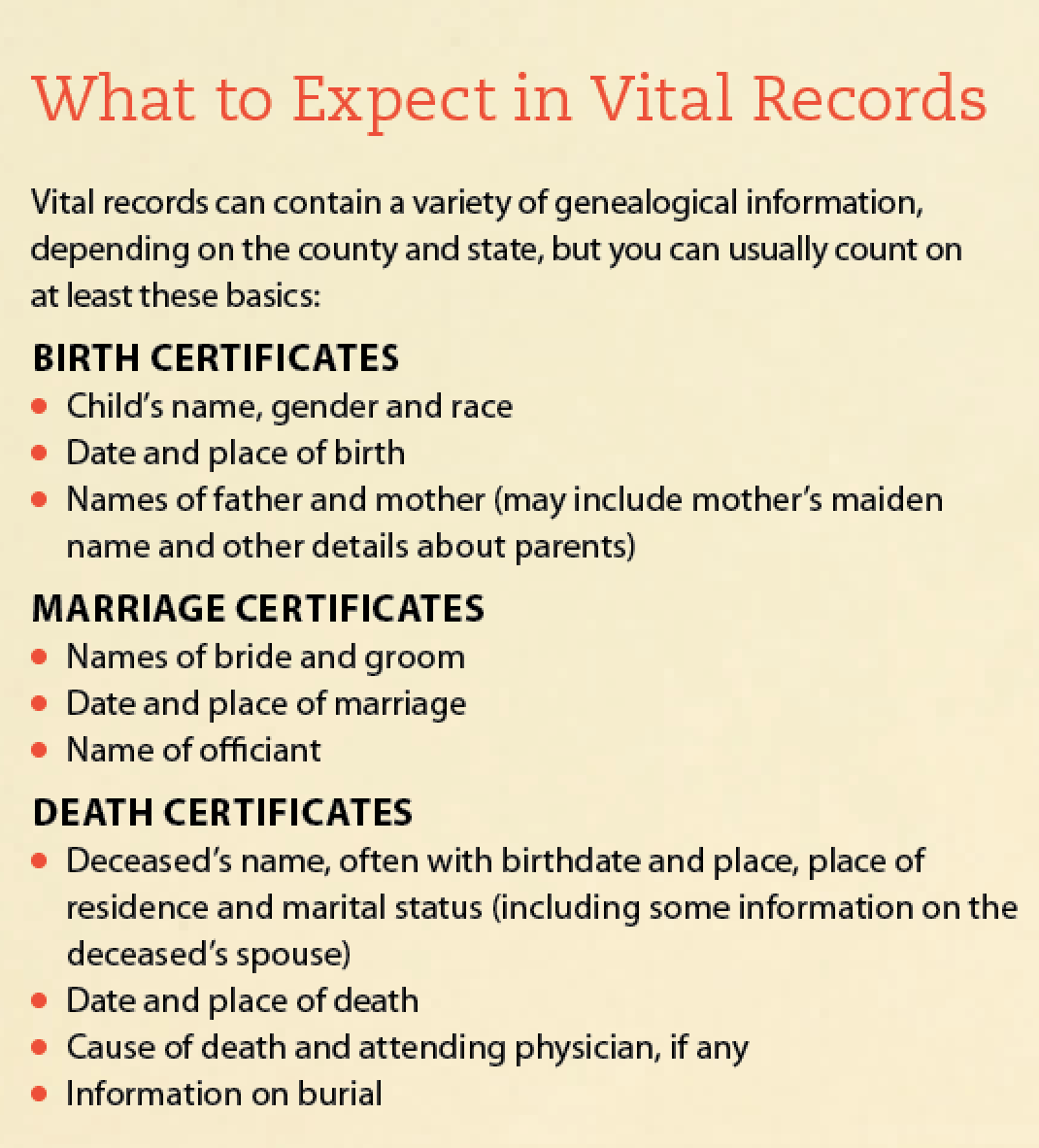

Congrats! You’ve finally tracked down a vital record for an ancestor’s birth, marriage or death. Now you can fill in blanks in your family tree. At last, you have a date and place for another key genealogical event. But don’t stop with those bare-bones basics. A close reading of vital records can often reveal other essential facts—ranging from the expected (such as parents’ names on a birth certificate) to surprising clues to family mysteries. Beyond the basics of when and where, vital record details include other family members, missing maiden names, an ancestor’s religion or military service, and even name changes and alternative spellings.

Death certificates, since they sum up the facts at the end of a person’s life, typically contain the most detailed information, including (of course) cause of death. It’s not unusual to find a person’s parents and their birthplaces on a death certificate. You you might also find this information on a marriage license as well as a birth certificate. Marriage records, often more like log entries, tend to be the least informative. But here, too, you can find surprises. And birth records can tell you more about the child’s parents and any other offspring than you might expect.

Digging into these details may require you to go beyond mere indexes of vital records. Instead, you’ll want to seek out the actual record (on paper or online) to see more than just the basic dates and places. That might mean writing to a county or state vital records office. (In this article, we’ve focused on US vital records. But you can also glean a lot from foreign records if they’re available.)

Here are some examples of surprises or unexpected info you might find in vital records. The amount you’ll find depends on the forms used by your ancestor’s locality and what facts informants knew or volunteered.

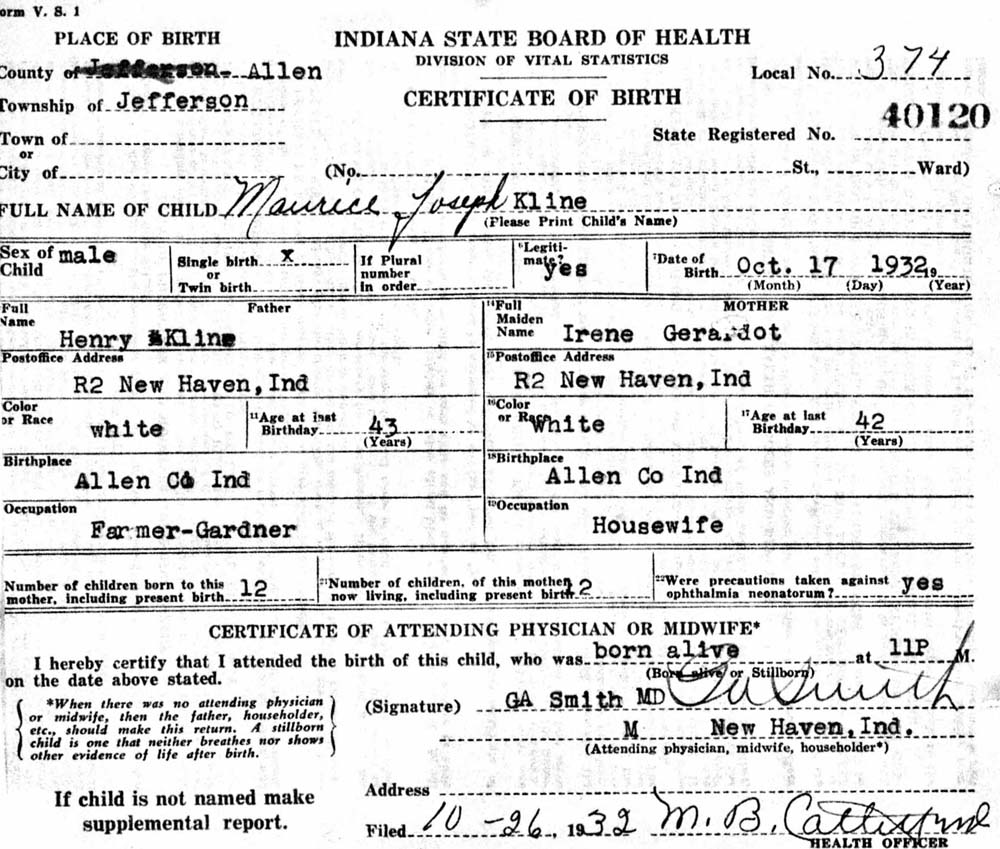

Birth Details

Birth and marriage certificates often give the couple’s ages and/or dates and places of birth, and death records may list parents’ birth details (in addition to those of the deceased). If it lists ages, the form may specify the event’s years, months and days, enabling you to calculate a birth date. There’s also often a question on a birth record asking if a birth was legitimate.

Maiden Names

Marriage records aren’t the only place to find a woman’s maiden name. Maiden names are often listed on children’s birth records or (later) on children’s death records. Maiden names in records allow you to go back a generation.

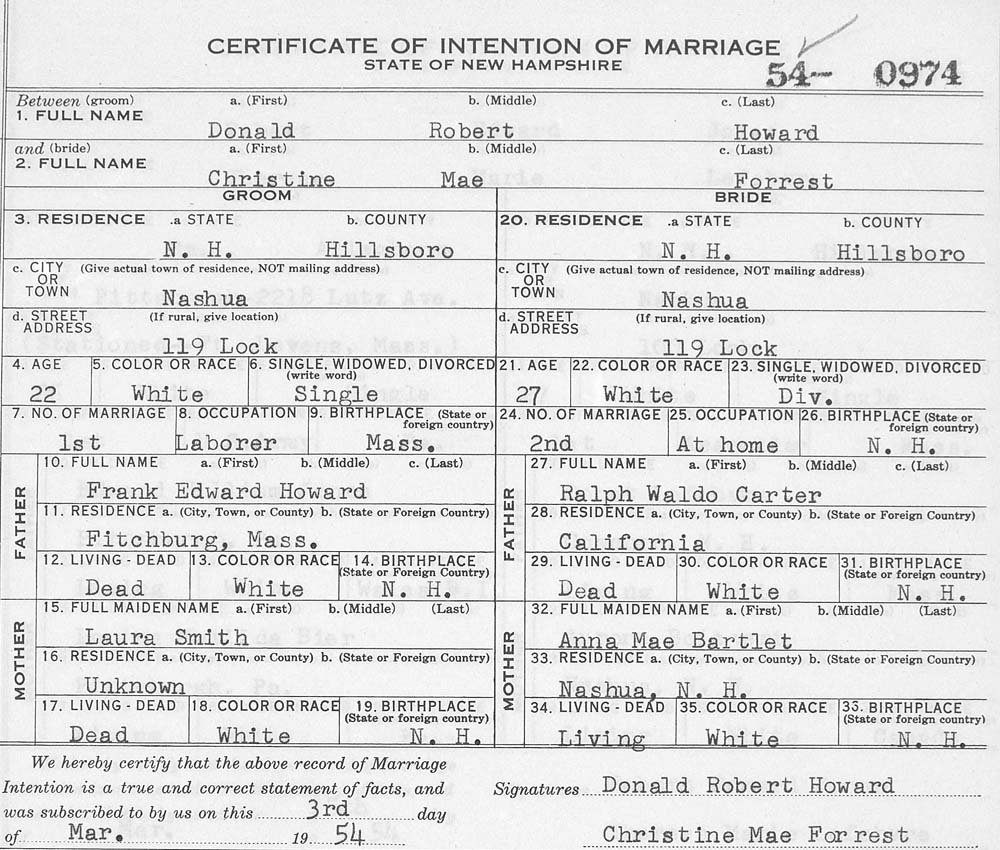

Parental Exceptions

Even where parents’ names are not ordinarily required on marriage documents, you might find an exception if the bride and/or groom were underage at the time.

The 1941 Florida application for marriage license for Russell Hobson and Vernee Laney, for instance, gives the mother of the bride’s name in a special section of the form. Vernee’s mother consented to the marriage, since Vernee was only 19. And the record attested that Vernee’s father (sadly, unnamed) had died.

Other Family Members

Check birth records to see if they include a question about whether this is the mother’s first child. It will often give birth order if not, as well as how many children are living. If you didn’t know Great-grandpa had siblings, this will clue you in.

Check marriage records for names of witnesses and, in early records, “bondsmen,” who often turn out to be relatives (or people who also later marry into the family).

Death records can provide clues when there’s a box for “Name of informant”—that is, who reported the death. This is most often a spouse (if one is still living). But the informant may be a relative you didn’t know about, or a name that connects with another piece of research.

Grace Lee Houston’s 1967 death in Virginia, for example, was reported by Edwin Giles Houston—presumably her son. Eva LeCompte’s 1950 New Hampshire death certificate is a bit more puzzling, listing “Mrs. George Poirier” as informant. That last name doesn’t match her father or her mother’s maiden name. Likely Mrs. Poirier is her daughter, listed in this record by her married name.

Occupations

It’s pretty common for birth records to list the parents’ occupation(s) and death records to give the deceased’s job and even employer. You might be able to use this information to dig into employment or other occupation-related records, such as those of the US Railroad Retirement Board.

Social Security Numbers

While you don’t need an ancestor’s Social Security number to search the Social Security Death Index (widely available online, including at FamilySearch), knowing the number can help you differentiate between similarly named individuals. Death certificates often include this number, so make a note of it just in case. If the certificate is vague or missing the person’s birth date, the SSDI can usually supply it.

Race

This might seem obvious, but don’t overlook the possibility that someone in the family listed in a vital record was of a different race. Census records sometimes fudge this fact, but vital records can reveal it.

Religion

Even if a certificate doesn’t specifically state an ancestor’s religious preference, you can often figure it out from facts listed on the form. Who performed the marriage? A Catholic priest? A Lutheran pastor? A rabbi? Was your ancestor buried in a Catholic cemetery, or some other denomination?

Places of Residence

Don’t assume an ancestor lived in the place where the event occurred. Crossing state lines to get married was common, for example. And people often died away from home (making it more difficult to find the death record in the first place). Records often give full addresses, enabling you to research further in city directories and censuses. Sometimes, as in New Hampshire and Nevada records, a death certificate notes how long the deceased lived in that location.

Military Service

Death records, in particular, often have a blank to indicate military service. James P. Dickinson’s 1947 Tennessee certificate, for example, lists him as a veteran of the Spanish-American War. You can also check to see if an ancestor died in a veterans’ hospital (Dickinson died in Kennedy Veterans Hospital). Or determine if he was buried in a national cemetery (as Dickinson was).

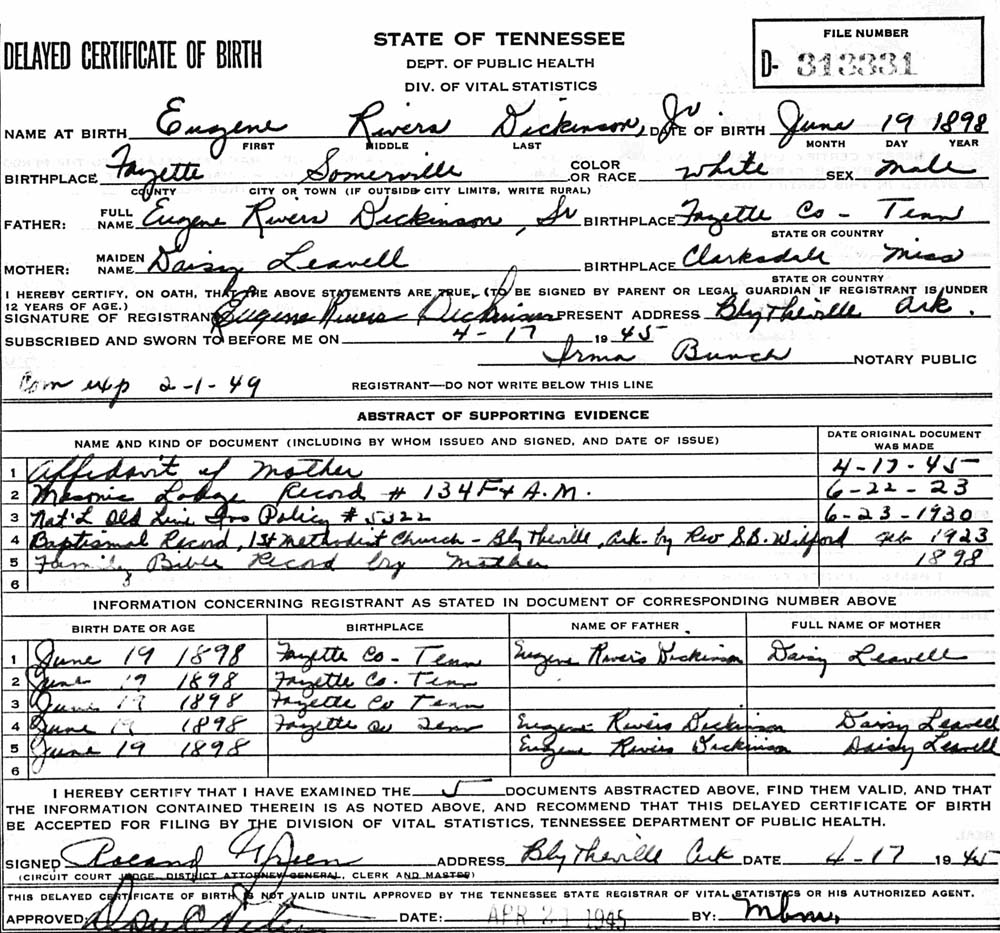

Other Sources

Delayed birth certificates, issued well after a person’s birth in order to obtain a passport or register for Social Security, list the sources of information proving the facts. These, in turn, can spark further research.

Rebecca Rice’s Virginia delayed certificate similarly cites a family Bible, published in 1859, that “contains an unaltered record of this birth apparently made near the time of birth.” (The certificate is also signed by Rebecca’s aunt, age 8.)

Marital Status

Death certificates usually name a spouse, if any, and have places to check whether the deceased was married, widowed, divorced or never married.

Unusual Causes of Death

It’s useful (and may be helpful for your own medical history) to know what caused an ancestor’s death. Sometimes, though, the circumstances are especially noteworthy. (I have an ancestor who died in a tornado in the middle of preaching a sermon.)

Places of Burial

Can’t find an ancestor’s burial place? Check the bottom of the death certificate, which might indicate a “removal for burial” to somewhere distant from the place of death.

Mary Miller’s 1965 Nevada certificate, for example, reveals that she was actually buried in Chester, Calif.—not in Reno, where she died. (This section also typically gives information about the funeral home, which might have other records you can research.)

Putting Clues Together in Vital Records

Sometimes the seemingly minor surprises hidden in your ancestors’ vital records can turn out to be important clues, unlocking whole sections of your family tree or solving stubborn mysteries.

In my wife’s family, for example, several people have the all-too-common surname of Miller. How can we figure out which Millers belonged to the family and which just had similar names? The 1924 Missouri death certificate of Henry G. Miller implied one important connection: The informant signing the document was Effie Forman, whose maiden name was Miller. Their relationship wasn’t stated, but this strongly suggested that Henry was her father—a suggestion that later proved accurate.

In researching another branch of my wife’s family, I found a 1926 Illinois death record for Samuel Bradbury, her great-great-great-uncle. Happily, it listed his mother’s maiden name as Mary Jones. Unhappily, this is about as common a name as possible. But I recalled an 1860 census entry for my wife’s ancestor Elizabeth Bradbury, who lived in the household of her father, John. In that entry, a non-Bradbury resident stuck out: Samuel Jones.

You’ll often need to combine finds from vital records with information from other sources to solve a puzzle. In records dated 1860, I found Mary Jones (mother to a Bradbury) and Samuel Jones living in the correct John Bradbury household. That household included a son, Samuel (another common name), born the same year as the Samuel Bradbury in the 1926 death certificate. The 1926 Samuel seemed to be Elizabeth’s brother—making Mary Jones her mother, too.

It took another death record (Elizabeth’s from 1929 in Illinois) to prove the connection. Just as with Samuel, her record helpfully listed her mother when I finally found it: Mary Jones. It also gave her spouse’s name, confirming I had the right family all along.

Spelling variations can be another kind of “surprise.” My wife’s South Dakota Norwegian ancestors had already documented some of her relatives, but I couldn’t count on the accuracy of those family histories. (No offense, in-laws, but it’s important to find proof.) I knew her ancestor Alfred Erickson had a wife named Isabel, both from family sources and the census. Those family sources gave her last name as Ven—but how could I prove this? (Their marriage info was from the same family account.)

Searching for a birth record for Isabel Ven initially drew a blank. So I started trying spelling variations and wildcards. In this case, the “surprise” turned out to be in the record itself. She “hid” as “Esabel Ven” in 1899 South Dakota birth records. The same record confirmed her birth date and parents’ names I had from family sources.

In my own family tree, that bondsman info I mentioned earlier turned out to be useful. The parentage of my third-great-grandfather, Joel Stow, had me stumped. Finally I came across an 1825 North Carolina marriage record for an Abraham Stow Jr. listing a Joel Stow as bondsman. That little detail at least gave me a name to investigate: If Joel was the brother of Abraham Jr., their mutual father must have been Abraham Sr. I eventually found a will for Abraham Stow Sr. that listed sons Abraham and Joel.

It’s unlikely I’ll ever find a birth certificate for Joel, since he was born well before most such records began in North Carolina. But a different kind of vital record—for someone else entirely—led me to evidence of his parentage. That’s the kind of pleasant surprise genealogists love.

A version of this article originally appeared in the July/August 2019 issue of Family Tree Magazine.