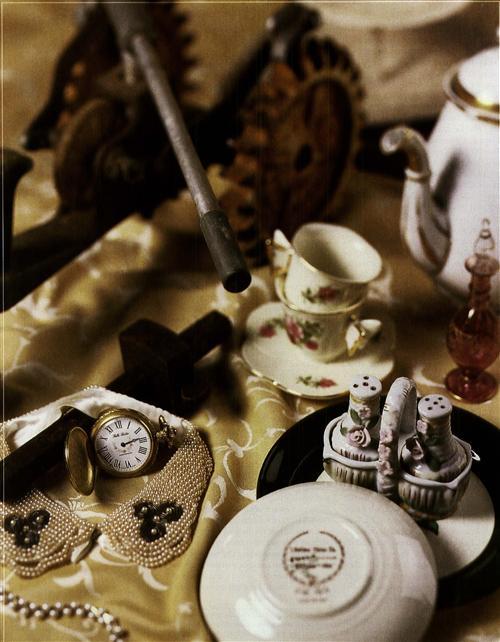

As a child, I was fascinated by the antiques in my paternal grandparents’ Ohio home: an English ironstone tea set, a copper bed warmer and an assortment of thingamajigs they’d repurposed as lamps. But I never thought to ask where these antiques came from, how old they were or even what they were until after my grandparents had died.

Although it’s too late to go straight to the source, it’s not too late to learn the histories of these heirlooms and their significance. In doing so, I’ve gained insight into my grandparents’ personalities and their ways of life. You can start investigating the stories behind your family’s keepsakes — and preserving them for future generations — by following these 10 steps.

1. Question your kin.

This is the easiest and most important step in researching an heirloom. What your relatives — and even family friends — already know might surprise you. Ask them who owned the object and when, what it was used for, where it was kept and why it’s significant. What memories do they associate with it?

My mom inherited a blue-and-white transfer ware serving platter from her grandmother Ferol Thuerk in the mid-1980s. Each year, Mom uses the platter on Thanksgiving and Christmas, but she hadn’t given much thought to its origins until recently. A few months ago, she asked her mother, Jean Howland, about the platter and learned that Ferol had purchased it at an antiques store in Bucks County, Pa. My grandmother Jean had accompanied Ferol on the shopping trip sometime while Jean was in high school, in the mid-to late 1930s. Now we know that Ferol was the first person in the family to own the platter; she didn’t inherit it from someone else.

Try to determine who originally owned each of your family heirlooms. And don’t make assumptions: You may associate those antique knitting needles with Grandma, but maybe she inherited them from her grandmother, and they’re older than you think.

If your far-flung relatives can’t see the heirloom in person, jog their memories by sending pictures. When I asked my dad what he remembers about his parents’ antiques, I didn’t get much of an answer. But after flipping through old photos, he recalled a lot more, including where my grandparents had displayed the furniture in his childhood home. For instance, the small, round table in the guest bedroom where I always stayed had once served as a dining room table; it’s hard to believe their family of four actually fit around it. I also learned that as a child my dad routinely scaled the 7-foot-tall cupboard in my grandparents’ dining room because they “hid” candy on top of it. My grandmother Maralyn Eisenstodt must have trusted her grandchildren more because she kept the candy inside the cupboard when we were young.

2. Examine home sources.

Lucky for me, Maralyn left a lot of clues about the origins of her precious belongings. (I learned this after asking my stepmom what she knew about them.) Before she died, Maralyn photographed each one and wrote captions on the backs of the prints, such as “Grandma Gustie’s two cut-glass tumblers from a wedding set” and “56-year-old milk-glass goblets — Christmas Dad to me.” The most interesting caption — “One of pair of OLD Hogarth prints bought Cincy when Dad needed shoes more” — reveals the sacrifices my grandparents made so they could afford the art they loved.

Your relatives may have left similar clues — not just on the backs of photographs, but also in diaries and journals. If your great-grandmother received a set of dishes on her wedding day, she might have written about it in her diary. Ditto if she saved for months to buy that china.

The best way to picture an heirloom in its original setting, though, is to look for it in old photos. Want to know where your mother got the dresser in her bedroom? Check out photos of relatives’ homes. You might find the same piece in a picture of your great-aunt’s childhood bedroom — and what do you know, it once had a mirror attached to it.

If you can track down household inventories, you’re really in luck. Your relatives might have created these documents in case of burglary or fire. They likely would have stored them in safety-deposit boxes or with trusted family or friends. You also might find an inventory of an ancestor’s estate in his or her probate file, which most likely resides at the county courthouse.

Maralyn created a room-by-room inventory almost a decade before her death, and she gave copies to both of her children. Examining this list today, I can see which pieces she treasured the most (from her annotations, such as “very valuable”) and even how much she paid for them. From this postscript, I also know she was always thinking ahead: “Check shoeboxes on my closet shelf for mad money, which I sometimes keep when I’m mad; beats lifting a mattress!”

3. Study the object’s shape, size, color and material substance.

Most of us can recognize jewelry, china and other keepsakes commonly passed down by families. But what if you inherited some weird gadget you can’t identify — how do you figure out what it is?

Start by describing the object in broad terms. Does it look mass-produced or handmade? Does it seem to be missing any parts? Could it be part of a larger device? Guess the object’s function and use.

Next, consider your ancestors’ hobbies and trades. Are there any craftsmen in your family, perhaps a jeweler or a carpenter? Might a relative have used the gadget in his profession? If so, consult Dictionary of American Hand Tools: A Pictorial Synopsis compiled by Alvin Sellens (Schiffer), and examine the tools for that craft. Did your grandmother love to cook? You may have inherited an antiquated cooking device, such as an ice cream mold or a butter curler. Linda Campbell Franklin’s 300 Years of Kitchen Collectibles, 5th edition, (Krause Publications) can help you identify it.

Now look more closely at the object. Do you notice any markings, such as a manufacturer’s name (usually on the underside of the object)? Take note of any decoration, which might indicate the time period. For instance, Colonial art often depicted kings and queens; after the Revolutionary War, George Washington’s bust and the bald eagle decorated ceramics and glass. If the heirloom looks handmade, one of your ancestors might have created it.

Don’t forget to look inside any object with a lid or drawer. For more than a year after Maralyn’s death, no one bothered to take the lid off her copper bed warmer. When my stepmom finally did, she found this note: “In June 1998, I saw a bed warmer not as nice as this sold for $506. I have owned it for 50 years.”

4. Look for a patent date and number.

A patent date on an heirloom can clue you in to which ancestor originally owned it. For instance, if the date’s 1885 and your greatgrandfather died in 1879, you know the gadget didn’t belong to him. Armed with the patent number (sometimes accompanied by the letters PAT), you can easily trace the object’s patent application, which could include original drawings. Just type the number into the US Patent and Trademark Office’s (USPTO) online database at <www.uspto.gov/patft>.

One of the many gizmos my grandparents turned into a lamp was an antique coffee mill, which my grandmother had painted teal. I couldn’t find a patent number or date on the mill, but I did see the manufacturer’s name — “Lane Brothers, Pough-keepsie, New York” — and the words “Swift Mill.” Flipping through 300 Years of Kitchen Collectibles, I found a picture of the mill, plus a patent number granted to a Beriah Swift of Washington, NY. I clicked over to the USPTO’s Web site and ran a patent-number search. The database brought up Swift’s Aug. 16, 1845, patent — complete with three drawings — within seconds. Now I know the Lane Brothers must have sold the mill after 1845.

The USPTO really could come in handy if you suspect your ancestor invented that gadget. Who knows: The farmers in your family tree might have put a new spin on the corn sheller or grain cradle. Search the USPTO database to find out. (For more on researching patents, read the April 2004 Family Tree Magazine.)

5. Research the manufacturer on the Web.

If your heirloom doesn’t have a patent number, try researching the manufacturer instead. Start by looking for the maker’s mark, which may include a factory name, pattern name, place of origin and some type of symbol. This will help you not only identify the maker, but also pinpoint the year the item went on the market, since some manufacturers used different marks over the years.

Once you’ve found the mark, type the manufacturer’s name or any other identifying information into Google <www.google.com> or another search engine. My search for “w & e corn,” the maker of my grandparents’ ironstone bowl and pitcher, returned 81 hits, mostly listings from antiques vendors’ sites. But I also found an overview of W & E Corn’s work on a Web site that’s dedicated to pottery made in Staffordshire County, England <www.thepotteries.org>. According to this site, the families of brothers William and Edward Corn manufactured earthenware between 1864 and 1891 in Burslem and between 1891 and 1904 in Longport. They used at least five different marks during that time, which you can see on the Web site. The mark on my grandparents’ pitcher depicts the British royal coat of arms and says, “Royal Patent Ironstone, W & E Corn.” I couldn’t find that mark on this site, but it appears that the Corns used the coat of arms throughout their career — which doesn’t help me narrow the time frame for the pitcher. The bowl’s mark, however, says, “Ceres W.E. Corn Burslem,” which means it must have been made before 1891, since that’s when the Burslem factory closed. Although I still need to do more research on the Corns, I now have some idea when and where they were in business, and when the original owner would have bought the bowl and pitcher.

Search carefully, and you might find a picture of your heirloom on the Internet. Try typing the manufacturer’s name into the Google search box and then clicking on Images. I searched for “johnson brothers,” the maker of a turkey platter that belonged to my stepmom’s maternal grandmother, Magdaline Sass. My search returned 1,380 hits, so I narrowed it by adding the word turkey. This time, I got only 10; the third hit was a picture of the platter in an antiques dealer’s online catalog.

As you search, try variations on the manufacturer’s name, such as “w & e com,” “w&e com,” “w and e com “ and “w.e.com.” Each time I searched, I got different results. And remember that you can’t believe everything you read on the Internet — even if an antiques dealer claims your great-aunt Dorothy’s shelf clock dates back to 1776 and is worth $10,000. You’ll need to confirm those figures in other sources.

6. Hit the books.

Old catalogs are great resources because they contain pictures and the original prices of antiques. Bloomingdale’s Illustrated 1886 Catalog by Bloomingdale Brothers (Dover Publications), for instance, can tell you how much clothing, jewelry and household items cost in your ancestors’ day.

Seek out old consumer magazines, newspapers and trade journals, too, for product descriptions and pictures. These sources also can tell you what your ancestors called that odd kitchen gadget when they bought it — and if you’re still stumped, what it was used for. Most large libraries have these publications on microfilm.

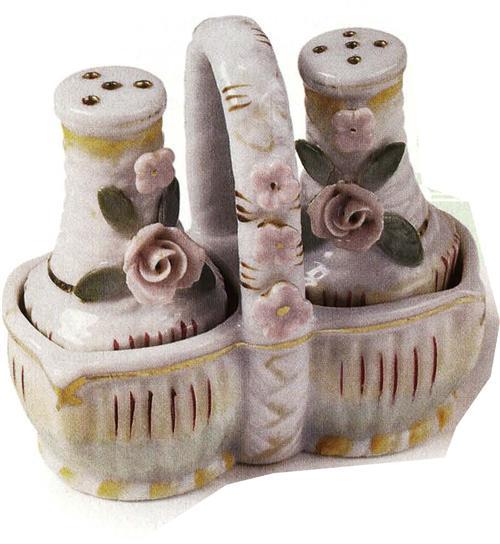

Illustrated antiques books hold even more clues. You can find books covering every topic imaginable — from Colonial artifacts to 1950s kitsch, 17th-century saws to salt-and-pepper shakers. You’ll even find publications devoted to artists’ marks. Use them to identify those weird symbols on your ancestors’ porcelain, pottery, glassware and metalwork.

I’ve consulted numerous antiques books in my research. One of those has helped me identify the maker of my mom’s blue-and-white platter. On the underside of the platter appear the words “Canova stone ware” and a picture of an urn, but no manufacturer’s name. I looked up Canova in The Dictionary of Blue & White Printed Pottery 1780-1880, 2 volumes, by A.W. Coysh and R.K. Henrywood (Antique Collectors’ Club) and learned that four potters used the word to describe their patterns — although only one seemed to be a fit. According to Coysh and Henrywood, the central scenes in all of Thomas Mayer’s works “include a large urn, and the border consists of scenic vignettes alternating with floral reserves” — that’s exactly how my mom’s platter looks. More research should reveal when Mayer was in business and confirm my hunch.

7. Track down city directories and business records.

After locating Beriah Swift’s patent, I still wanted to know when the Lane Brothers, who manufactured my grandparents’ coffee mill, owned their factory. So I searched for a city directory.

Similar to today’s telephone books, city directories list a town’s inhabitants alphabetically. Although some cities printed directories as far back as the 1700s, most began publishing them annually or every other year in the mid-to late 1800s. Directories usually list all adults in a household, plus their occupations, employers’ names and home address. Many city directories also include a business directory, which will benefit your heirloom research the most.

The first place to look for a city directory is the library in the area the directory covers. You might find these resources on the Web, as well. Subscription site Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > has transcribed directories from all over the country. I searched the Poughkeepsie, New York Directories, 1890-1897 database for the Lane business and found J.G. Lane and W.J. Lane at “foot Prospect” through 1897; their occupations were listed as “mfrs coffee mills, etc.” I’ll need to look for earlier directories to find out when the Lane brothers started their business, but this is a good jumping-off point. In fact, if I look in old catalogs from the 1890s, I might find a picture of my grandparents’ mill.

City directories also can come in handy if you inherited an old tool that you suspect a relative used in his or her occupation. Some directories will indicate people’s professions. Look up your great-grandfather, and you might learn that he used that swarm catcher in his beekeeping business.

Think your grandmother might have sold bottle openers (like the old-fashioned one you inherited) in her general store? Your family still might have business records, which could list store merchandise. Or check with the local historical or genealogical society to find out what might have happened to those records.

8. Pull out your family tree.

What if you’ve found your heirloom in an old catalog or antiques book and tracked down a city directory, but you’re still not sure who owned it? How do you find out? You’ll have to work backward by considering the date the object was made and then referencing your family tree. If you found your keepsake doll in an 1886 catalog, it probably didn’t originally belong to your mother, who was born in 1916, or your grandmother, who was born in 1888 — unless one of them bought it used. So perhaps your great-grandmother or great-great-aunt owned it. Or maybe one of them bought it for your grandmother’s older sister or a cousin. Photographs and journals can help you connect the dots.

9. Keep your heirloom in tiptop shape.

You’ll want to preserve your keepsake so you can pass it down to your descendants. Be sure to handle it with clean, dry, lotion-free hands, and store it in a place with moderate temperature and humidity. Extended exposure to hot and humid conditions will promote mold and mildew, and could cause chemical deterioration in metals and plastics. Conversely, low humidity may damage wood and leather. Avoid storing your heirloom in an area with frequent fluctuation in temperature and humidity, such as an attic, basement or garage. (These areas also are prone to dust, pollutants and insects, which can do even further damage.) Keep your heirloom out of direct sunlight, too, so it doesn’t fade.

A conservation guide, such as Caring for Your Family Treasures: Heritage Preservation by Jane S. Long and Richard W. Long (Harry N. Abrams), can provide tips for preserving specific materials. Or contact The American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works <aic.stanford.edu> or a local museum to find a professional conservator in your area. Pay extra attention to textiles and papers, which deteriorate much faster than, say, ceramics or metals.

10. Record the keepsake’s story.

After all your detective work, don’t forget to record what you’ve learned. Your ancestors might not have left you inventories, but you should leave one for your descendants. For each keepsake, jot down who owned it originally, when and where it was made, how you came to own it and any stories associated with it. Also be sure to include the object’s actual name and a description of the way it was used — you might know what a hair receiver is, but your great-grandchildren probably won’t.

To create your inventory, you can use the handy (and free) Artifacts and Heirlooms form at <www.familytreemagazine.com/forms/download.html>. Or pick up The Heirloom Diary, an attractive, lined journal with space for recording a description of each keepsake, plus an appraisal, stories and more (from Galiant Enterprises, 410-552-1456, <www.theheirloomdiary.com>). Keep one copy of the inventory with your important papers and another with your genealogical files. You’ll make your descendants extra happy if you include photos, as my grandmother did.

As you investigate your heirlooms, you’ll uncover all kinds of fascinating facts and stories about your ancestors, and you’ll get a glimpse into their everyday lives. You might even uncover more family treasures as you ask relatives about those in your possession.