Your ability to understand what a source is and how reliable the information it contains lies at the heart of all genealogical problem-solving. Not all sources are equal. You have to know the quality of the source that your information came from. The first step to knowing the value of your source is to determine if the source is original, derivative or authored. To determine that, you’ll start by evaluating sources and how they were created.

Evaluating sources: What is it?

A genealogical source is a physical item or artifact that tells us something about the past. This can come in many forms, including photographs, documents, interviews and oral histories. You may have learned terms like “primary source” or “secondary source” to describe sources. However, we’re not using those terms here because it’s possible for a single genealogical or historical source to report both primary (first-hand) and secondary (second-hand) information. Use our free source documentation guide to keep track as you research.

We’ll talk more about the information reported within a source below. For now, let’s look first at the physical source itself. It might be:

- An original source, the first format a source ever took.

- A derivative source created from the original, but modified in some way, like an index, transcript, translation or abstract (summary) of the original.

- An authored source. Authored sources entail more than simply reiterating or compiling information from another source. It includes the author’s analysis or original thinking, which often results from consideration of many sources.

Why does it matter what kind of source it is?

Original sources are the records we most want to consult. They generally haven’t been tampered with, or at least the possibilities for tampering are far less than when someone has altered or interpreted the source in some way. Therefore, this means your ability to judge the content will be more straightforward.

If we’re looking at an original diary, we can investigate whether pages have been torn out, notes or doodles appear in the margins, anything has been crossed out, and so forth. We can read the text as it was written. We don’t have to wonder whether a well-meaning transcriptionist censored great-grandpa or left out a critical word or phrase.

Derivative copies, on the other hand, may not communicate everything you need from the original record. Each layer of tampering adds the possibility of human error. For instance, indexes, abstracts, and footnotes in a larger work summarize what you want to know. By their very nature, they often deliberately leave out some material. Translations and transcriptions don’t preserve the original handwriting and may mis-word the text.

Typed vs. original sources

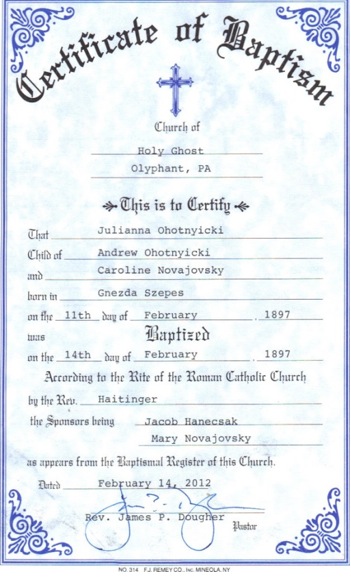

Le’ts take a stab at evaluating a source. Shown here is a baptismal certificate from a Catholic parish. This research anecdote has a happy ending but serves as a warning about what you might miss with a typed certificate. I wasn’t allowed to view the original entry in the parish baptismal register, which is common. Instead, the parish secretary sent me this typed certificate, which states that the baby was born in “Gneza Szepes” (a Slovakian village) and baptized three days later in the United States. That wasn’t physically possible in 1897!

I asked the parish secretary for clarification. She re-checked the record. Gnezda Szepes was the birthplace of both the child’s parents. In this case, the parish secretary’s mistake worked in my favor because she shared a critical fact that otherwise would not have appeared on the form. There’s simply no place to enter that information! That was definitely a case of genealogy serendipity. However, it taught me to trust less in typed certificates as a rule. I learned first-hand what I could be missing out on.

So does that mean that derivative sources are worthless?

Not necessarily. There are times that derivative sources and authored works expand our understanding of a record. An index may help us see at a glance that several relatives from the same extended family appear in a recordset. A translation, however imperfect, may get us closer to understanding the text than we would get on our own. And an authored work may be well-reasoned and packed with cited information we want to know. At the very least, it may contain some great historical context.

That said, whenever you’ve discovered the existence of an original record through mention in a derivative or authored record, try to track down the original. You’ll usually get the most complete, unaltered version of the tale it has to tell.

How can I tell whether a source is original, derivative or authored?

Often it’s not difficult to tell. Perhaps that original source looks just like you’d expect (old, worn, handwritten). You found it in a place you’d expect to find an old record: in an archive or in your grandmother’s attic. Derivative sources often identify themselves as such in the title or introductory pages. Authored works are published, publicly attributed to the author, etc.

However, always watch for any indications to the contrary. I have worked with old manuscripts that appeared to be originals, but parts of them were copies. Clerks working in the mid-1800s transcribed even older records from a previous volume into that one. I’ve seen this occur with church records and with deed records that were transcribed from the old county’s record when a new county was formed. (The old county’s records needed to be copied for continuity’s sake.) When researching probate records, you may find yourself looking at a court-created copy of a will, rather than original.

Within a record itself, you may find mention of whether it is a copy or transcript from an older record. Look in any introductory pages and in headers or explanations within the text.

The handwriting in the record itself may be a giveaway. If it’s a list of entries purportedly created over a long period of time (like a death register), does it all appear to be written in the same handwriting, even written by the same pen? Even if one long-lived scribe handled all those entries and never altered his or her handwriting style, you should see variations in ink tone, thickness of pen/brush strokes, handwriting angles and even changes in how names or dates or other data were written, all of which show evidence of separate entries being made over the course of time.

Check the description for clues

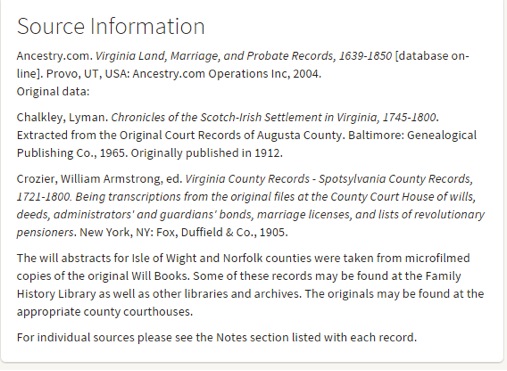

When evaluating sources online, look at the records collection description, like the screenshot shown here for Ancestry.com’s database, “Virginia, U.S., Land, Marriage and Probate Records, 1639-1850.” The first paragraph identifies the name of the Ancestry.com database, itself a derivative record. There are no images attached to this database, just indexed entries.

The following paragraphs of the collection description tell where Ancestry.com got its information: from extracts in a published book of Augusta County court records, published transcriptions of various Spotsylvania County records and microfilmed copies of original will books. In other words, this is an index that was created largely from other published indexes and transcripts.

Do you see how that weakens this record collection’s power as a source? The index may not be complete or fully accurate. Several opportunities for mistakes exist between the creating of the original records and the creating of this one. While this index is a valuable tool, it is not a solid foundation for a researcher. Use it not as your final source, but to track down the original.

How do I find original records if I’m looking at a derivative?

The good news is that most derivative records will tell you something about the original records, or the records from which they are created. Specifically, you might learn whether they still exist and where you can find original or imaged versions. In the online record collection description above, it says, “Some of these [microfilmed] records may be found at the FamilySearch Library [in Salt Lake City] as well as other libraries and archives. The originals may be found at the appropriate county courthouses.” The very last sentence indicates that even more information may be found in the Notes section for each individual record entry.

Published transcripts, abstracts and indexes of records will also usually indicate the original source of the records and where to find it now. In those cases where the record doesn’t tell you, look at the publication date and take heart. You can theorize that as of the publication date (or around there), the original record (or some other version of it) existed somewhere. Try contacting the author, publisher, web host, society or other entity associated with the version you found. Then contact libraries, archives and other repositories that would be logical hosts for that record.

Is an image copy as good as the original?

We often find ourselves looking at microfilmed, digitized and/or photocopied versions of records. Are these image copies considered the same as looking at originals? Or, should you approach these with the same cautions you use when working with derivative or authored copies? If there’s no sign that the image copy has been altered, then you can consider it the same as looking at the “real thing.” Look specifically for blurry text, missing pages or information that’s been cut off.

Remember that the “real thing” may vary itself. It might be an authored, derivative or an original source. If your image copy seems altered or the copy quality is poor enough to make it difficult to read, think of it as a derivative copy. Then, hunt down the original or another copy, if possible.

Tip: Check for the same record online in two different databases. Sometimes, one copy will be better than the other.

What if the original source no longer exists or I can’t access it?

Sadly, you will find cases in which the original source has been destroyed or lost. You may also come across records that still exist, but are so rare or fragile that they are closed to researchers. Some original records are closed for privacy reasons, and you may or may not be able to access any information from it (like that church baptismal record I showed you or Social Security applications for certain people).

Make every effort to access a record in as close to its original form as possible. A photocopy of the original is better than a typed transcript. Where you have no access to an existing original, try to consult politely with the records custodian (like I did with the parish secretary) to gain additional or clarifying information. Document your efforts. Then use whatever information you do have, noting its limitations. Try to corroborate weaker sources with additional sources.

Related Reads

Last updated: September 2021