Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Citations are among the most talked about—and, perhaps, most dreaded—aspects of family history research. Family Tree Magazine Editor Andrew Koch has called them the genealogical equivalent of flossing your teeth—a beneficial habit that few are excited to adopt.

But source citations don’t need to be scary, overly complicated, or dull. For more than a decade, Elizabeth Shown Mills, well-respected speaker and author of Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace (Genealogical Publishing Company), has been a leading expert on genealogy source citations. Her book regularly appears on must-read lists for family historians (including Family Tree‘s), and contains hundreds of easy-to-understand citation templates that make documentation a snap.

A revised fourth edition of Evidence Explained was published in early 2024. In honor of its release, Shown Mills answered some questions for our staff. Her answers will help you reframe how you think about source citations, and give practical ways of incorporating them into your research.

What inspired you to first write about source citations?

Elizabeth Shown Mills (ESM): Once upon a time, I was a very young newbie—consumed by curiosity, with no idea of what to do or how to do it. Someone told me about a book with a brief write-up about Grandma’s family. Christmas was around the corner and I had not found a suitable present for her, so I ordered the book.

Prior to wrapping it, I went to the library and photocopied the relevant page to file away in The Great Genealogy Notebook I had begun. Just that page. I didn’t “waste” my babysitting money on a copy of the book’s title page. But instinct told me I should identify where it came from, so I penned on the bottom of the photocopy: “From the book I gave Grandma for Christmas.”

A couple of years passed and, while thumbing through my Great Genealogy Notebook, I came across that photocopy of that page. Of course, having “looked at” hundreds of books in the meanwhile, I had no recollection of what book that page came from. Meanwhile, Grandma had passed and her things had scattered among numerous offspring.

No one recalled the book. Lesson learned.

Fast forward a few years: I’m married. Hubby and I are history students. We’re both dabbling in genealogy. Grad school introduced us to Turabian’s manual [A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations by Kate L. Turabian], which made book-and-article-citing so simple. Yet most genealogists we encountered didn’t bother—just as I hadn’t bothered with Grandma’s present.

So, in 1979, as a new Ph.D and a new Certified Genealogist respectively, Gary and I penned an article for what was then genealogy’s most-popular self-help magazine and people-finder, The Genealogical Helper: “How to Properly Document Your Research Notes,” Helper 33 (September-October 1979): 7–11. [Read the article on FamilySearch.]

At a conference the next month, a genealogical publisher cornered us: Would we be interested in doing a book? A book? A whole book on source citation? How boring! We demurred. A friend at our elbow volunteered. Thus was born the first real guide on the subject for genealogists: Richard Lackey’s Cite Your Sources.

Years passed. Richard also passed, and his guide was not updated. By the mid-90s, it was considerably outdated, to the distress of the Board for Certification of Genealogists and all the applicants who were told to follow it.

As the newly minted president of the Board, I cringed at each complaint the Board’s executive director shared with me. As I finished my term and passed the reins, he (the late, great John Frederic Dorman) propositioned me: Why don’t you use some of your newly freed-up time to update Lackey?

I yielded. The result was not just an update, but an entirely different book with a premise that was then quite controversial. Traditionally, students are taught that we cite sources for two reasons: 1, so that others will know where we got our information; and 2, so our source can be relocated by anyone who wants to find it.

Those reasons remain valid, but that little 1997 guide to citation, Evidence! Citation & Analysis for the Family Historian, moved the emphasis from sources to evidence. A far more important reason why a genealogist should cite each source is something we do for ourselves, not for others: We need to capture details that enable us to evaluate each source, appraise the reliability of its information, and make research conclusions on the basis of the best evidence possible.

That little Evidence!, which codified the rather-random citation practices of its era, opened a Pandora’s box. It was double the size of Lackey’s guide, but much remained uncovered. An explosion of genealogical education had introduced researchers to many new record types, as well as standards.

A citation template … needs flexibility. We can’t be hide bound to some rigid formula.

Elizabeth Shown Mills

Technology was introducing new media formats for the delivery of materials. Every day’s email brought a host of questions as to how to handle this-or-that oddity. In 2004, I sat down with all those inquiries and began the effort to corral a thousand one-offs into a more-systematic approach that would work with all record types and all media formats.

Thus was born, in 2007, the first edition of Evidence Explained, designed to help history researchers use all those sources that standard guides such as Chicago [Manual of Style] and MLA [Modern Language Association] do not cover.

You write that “Citation is an art, not a science.” With that in mind, how should genealogists think about citing sources?

ESM: The “art” of citation is evident when we consider that third and most-important reason for citing sources: We identify our source for each piece of information so we can reach more-reliable conclusions based on the best evidence possible.

That premise requires us to think about each source. Instead of saying “Oh, that’s a ‘marriage record,’ so I’ll use our software’s template for ‘marriage records’,” today’s genealogist is now thinking:

- What kind of “marriage record” is this?

- Is this a license or a bond, with no recorded return by a minister or judge?

- Is there no return because no marriage actually occurred?

- Is that license or bond copied into a register, where the details of the actual marriage should have been recorded also? Or, is this license or bond a loose piece of paper that might, at one time, have been attached to a now-lost return?

All of these questions affect our genealogical decision as to whether our John Smith actually married Mary Brown—or whether he might be the John Smith who, three months later, married a different woman.

These issues also affect how we craft a citation. They affect the details we record and how we explain them. Therefore, a citation template for a “marriage record” needs flexibility. We can’t be hide bound to some rigid formula.

There’s also a far bigger issue. Citations in science and similar fields focus almost exclusively on published materials: books and articles that have been vetted and edited—publications that are simple to cite. That’s a radically different world from genealogy, where sound research is based on original documents, created under wildly different circumstances by a legion of individuals with their own whims. We use records that survive randomly, are scattered in all types of repositories, and delivered to us today via a plethora of media. Simple, formulaic citation templates just don’t allow the flexibility we need.

And so, Evidence Explained (EE) 2.1 tells us:

Citation is an art, not a science. As budding artists, we learn the principles—from color and form to shape and texture. Once we have mastered the basics, we are free to improvise.

Evidence Explained, fourth edition by Elizabeth Shown Mills

Which details are the most important to cite?

ESM: EE’s new fourth edition is radically revised (and streamlined) in an effort to help budding artists learn those principles. A new chapter, a tutorial titled “Building a Citation,” introduces seven building blocks that can be mixed and matched as needed.

Each building block answers one of five basic questions: Who? What? When? Where? and Why should I believe this in the first place? Depending upon the source, some questions may need to be answered more than once; and a citation may or may not need to use all the blocks.

The seven building blocks are these:

- Creator (Who?): All sources have a creator. Evidence-style citations begin with the identity of the creator—if known.

- Title (What?): After our citation identifies the creator of the source, we then identify what they created. This will be a specific title—one we quote exactly. If the source has no formal title, then we create an identifier, using our own words without quote marks.

- Descriptor (What?): Many titles need explaining. We may need to state whether the source is a CD, a database, an audio or video recording, or part of a series of 27 volumes. Or we may need to point out that Deed Book 7 (1700–1712) is a transcribed copy, made 100 years after the dates that are on the cover. Points like the latter do matter, because every time a copy is made, errors are introduced. When we find conflicting information in our sources, the reason often stems from copying errors; we need to be able to identify which conflicting source is an original and which is a potentially problem-riddled copy.

- Place (Where?): For books, articles, and websites, the place where the work was created will be its place of publication. If a website, the place of publication is the URL. If the work is an unpublished manuscript, the place will be the repository, city, state where the work is held.

- Date/Year (When?): For published works, this will also be the date or year of publication. For manuscripts, it will be the date or year created. If it is an unpublished manuscript in private possession, the When? questions include the date or year we accessed the record at the place we cite for it.

- Publisher (Who?): This field, of course, will not be used unless a source is actually published—in print or online.

- Specific Item (Where within?): This field is highly flexible. Here we can add as much as needed to identify a specific item in a register, file or collection, as well as the specific spot in the source where we found the information we are using. The details we place here may also answer other Who? What? Where? When? Why? questions—as when we need to fully identify which birth registration we take from a cited database.

These seven building blocks are basically common-sense items. But knowing them—or having a list at hand—will keep us from forgetting to record essential details. The new edition of EE also uses these seven building blocks to create 14 universal templates that can be followed to cite any source, anywhere. And each citation example in EE’s 12 record-focused chapters is keyed to one of the templates.

What are multi-layer citations, and why are they important?

ESM: Layers are essential to modern citations when we cite record images online. Typically, for images, we have two or three layers, all cited in the same “sentence,” with layers separated by semicolons:

- one layer will cite the original record, as much as we can identify from the images themselves

- a second layer will cite the website and its database that provides the images

- a third layer, if needed, will report any source information the website provides about this set of images

Using layers ensures that details from the source will not be mixed with (and confused with) details from the website that provides the images. This is critical for many reasons. For example:

- Online providers often put their images into databases for which they create their own titles. The actual records will carry different titles. If we use the website’s database title as a substitute for the record title, then we make it nigh impossible for anyone to use our citation to find the original record after the website goes defunct or restructures its architecture with different URLs or different menu paths.

- Online providers may or may not identify a record correctly—a problem that happens far more often than we expect. This is why our identification of the original should stick strictly to what we see on the images themselves. And then, in our final layer, we report whatever additional information the website tells us about the identity or location of the document.

What citation mistakes do genealogists commonly make?

ESM: Ah, mistakes! We’ve all made them, and our past mistakes will always haunt us. The most serious of all is simply failing to identify our source; any citation is better than nothing (unless we write “from the book we gave Grandma for Christmas”).

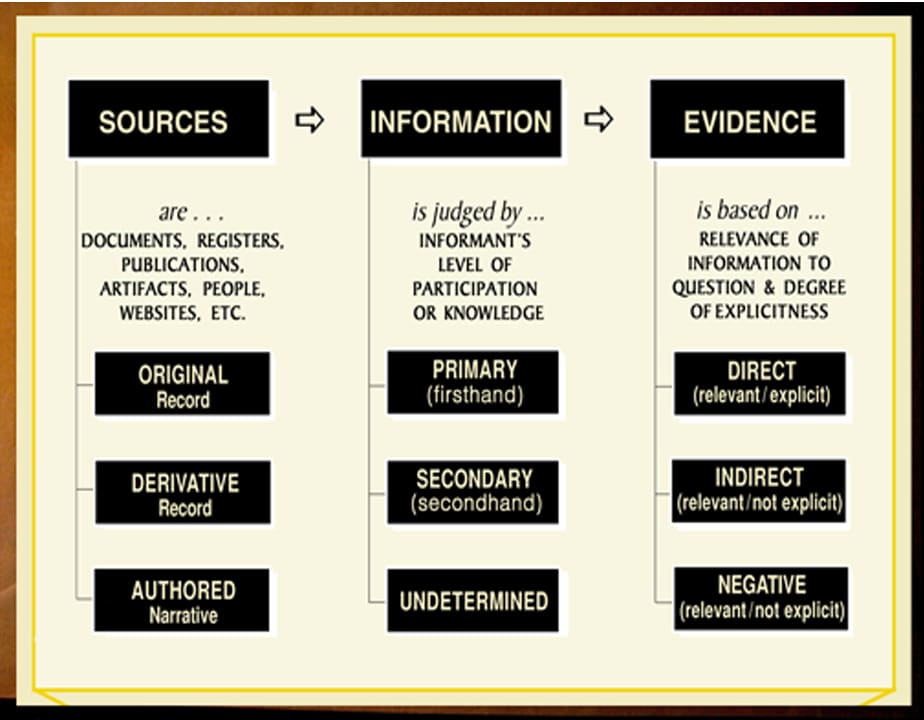

Beyond this, most of our problems happen when we fail to realize one thing: All sources are not created equal. Some help us and some hurt us. That’s why we record enough details to evaluate information by EE’s “Evidence Analysis Process Map,” now used by most genealogical educators, journals and certifying boards.

Following this simple diagram, we evaluate:

- Sources by whether they are original records, derivative copies, or narrative discussions that mix factual information with the author’s interpretations or conclusions.

- Information within the source, piece by piece. We consider whether it came from firsthand knowledge (primary information) or an informant with secondhand knowledge (secondary information), or whether the informant is unknown.

- Evidence that we draw from that information. Here, we consider whether that evidence is direct (an explicit statement that directly answers our question), indirect (a statement that seems to be relevant but must be combined with other information to arrive at an answer to our question), or negative (the absence of information or situation in circumstances in which that information or situation should exist—e.g., Sherlock Holmes’ “sound of the dog not barking” when a horse was stolen).

How has genealogy changed since you published the third edition?

ESM: There’s both good and bad to note here. Billions of more records have become available—often new records that even long-time researchers have not encountered and may not know how to interpret or handle. Meanwhile, websites offer information through complicated architectures whose paths are often hard to follow, even though the omission of even one step along the path might make it impossible to relocate a record.

EE’s fourth edition, although streamlined, has a stronger emphasis on digital sources because those are the ones most researchers now use. However, technology has not changed one thing: the need to understand the records we use. EE is not just a guide to the mechanics of citation. It’s a guide to historical records.

Some users, naturally use EE reactively: They query online for an ancestor’s name, find something, then look in EE to see how to cite what they’ve found. EE is more valuable if users will use it proactively: Read the chapters, as time permits, [to] learn about many different types of records that they are not yet familiar with, and discover where to go to find these types of records.

Citation simply means identification—and it’s something we do for ourselves, not for others.

Elizabeth Shown Mills

Which source(s) do you find the hardest to cite?

ESM: Personally, I’d replace the word hard with confusing. The actual problem is not that a citation is hard to create. The root of the problem is our need to understand the record itself—and, for digital sources, the structure of the website.

Understanding the source and the process by which it was created is always worth the time that we invest. Not only does it help us avoid undue trust in unreliable sources, but it also points us to other new and wonderful records that were part of the process. Understanding each website and its own structure is how we ensure that we can find again the fantastic document we stumbled upon, even after the website is rejiggered six months or six years from now.

That said, your use of the phrase “hardest to cite” does reflect a common reaction to the issue of citation. EE’s goal is to help new researchers toward the Aha! moment in which they realize that citation isn’t all about trivial details and punctuation. It’s not about following some pattern so the “Citation Police” will leave us alone. Citation simply means identification—and it’s something we do for ourselves, not for others.

Understanding each source, and knowing what details are needed to identify it, is how we avoid mistakes and brick walls. It’s how we avoid filling our trees with fictional people or names that end up being “former ancestors” when we eventually discover that we should not have accepted claims we found within unreliable sources.

An abridged version of this interview will run in the July/August 2024 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in affiliate program through Amazon Services LLC Associates and the Genealogical Publishing Co. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.