1820 is a watershed year for genealogists – that’s when the US government started requiring ships captains to keep lists of their passengers. But what if your ancestors arrived on US shores before that magical date? Does that spell the end of your genealogical road?

Not by a long shot. True, Colonial immigration records are scarce and incomplete, and they don’t look like the more-familiar post-1820 passenger arrival records. But your early immigrant ancestors left behind other documents to help you trace their paths back across the Atlantic – a paper trail much like a trail of bread crumbs. Sources such as published compilations, naturalization papers, church records, land transfers, personal papers, court documents, and, yes, a few passenger lists all can lead to new discoveries.

A brief history of European migrations to the US

Finding where your ancestor’s pre-1820 migration started and ended relies on a combination of genealogical and historical research. Immigration usually happened in waves, and it’ll help to know which one your ancestors rode to American shores. Start by reading a town or county history for the area where they lived to learn who established the community and the groups that moved there. Create a timeline of each ancestor’s life, beginning with his death and working backward, then compare it to local and national occurrences.

A quick overview: Spain got a colonization jump on England, establishing North America’s first permanent European settlement in 1565 at St. Augustine, Fla. But the vast majority of 17th-century migrants came from Great Britain. Settlers trickled in after the founding of Jamestown in 1607. Then from 1620 to 1643, the Great Migration saw more than 20,000 men, women and children – mostly puritans seeking freedom from the official Church of England – relocate to what would become New England.

Later that century, many Quakers, moved from England to Pennsylvania. That colony’s founder, William Penn, published pamphlets in German urging other religious groups to immigrate, among them the Mennonites, Lutherans and Moravians. Commercial enterprises such as the Virginia and the Dutch West India companies funded colonies to make a profit through trade with England. Dutch traders set up shop along the Hudson River in New York and French Huguenots settled in the Carolinas, Virginia, Pennsylvania and New York.

Groups continued to flow into the Colonies, with some, such as the Scots-Irish, driven by political unrest and others forcibly moved. Dutch ships first brought slaves to Jamestown in 1619. England used America as a penal colony, sending those facing death sentences to the southern Colonies, offered especially Maryland. Some Colonies offered enticements to lure immigrants: Governor James Edward Oglethorpe of Georgia, for instance, promised 50 acres of land per family. Those too poor to buy passage to America could sell their services to colonists; these indentured servants typically worked under contracts ranging from seven to 14 years.

In the early 18th century, land disputes in Europe prompted thousands to leave Germany’s Palatine region, particularly for New York and North Carolina. Later, during the Revolutionary War, immigration slowed, reaching earlier levels only after the Treaty of Paris ended the conflict in 1783. Finally, to regulate the tide of immigration, the new government formalized the immigration process in 1820.

8 records to research

Before you dive into the following records, advises New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS) librarian David Dearborn, learn as much as possible about your ancestor: age, occupation, marital status, any traveling companions. Not only will this information help you guess when the person immigrated and decide where to look for records; you also can use it to identify your ancestor in a list of same-named people. Consult these records as substitutes for modern passenger lists.

1. Published sources

Take a research shortcut by looking first at rosters other researchers have compiled. Your ancestor may appear in Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s by P. William Filby and Mary K. Meyer. This list of nearly 500,000 emigrants, built from a variety of records, is in print at many libraries (be sure to check the supplementary volumes).

The Great Migration Study Project publishes a book series giving comprehensive accounts of every known person who arrived during the 1620-to-1643 immigration wave. You can browse a free list of surnames on the site, but you’ll need to consult the cited book to see additional data. NEHGS members can search information from 1620 to 1633 online.

You’ll find even more promising compilations in the Library of Congress’ online guide Immigrant Arrivals: A Guide To Published Sources.

2. Passenger lists

We’ve dug up a few exceptions to that rule about nonexistent pre-1820 passenger rolls. Philadelphia passenger lists from 1729 through 1808 (with a break during the American Revolution) are transcribed in Ralph B. Strassburger and William J. Hinke’s three-volume Pennsylvania German Pioneers, searchable on Ancestry.com. A smattering of Boston lists exist in the form of impost records (logs of ships’ cargoes) covering 1715 to 1716 and 1762 to 1769; they’re published in Port Arrivals and Immigrants to the City of Boston compiled by William H. Whitmore (Genealogical Publishing Co.). The NEHGS library has a 1712 list for Boston.

The Alien Act of June 25, 1798, required customs officials at American ports to keep lists of all non-British arrivals, including each person’s name, age, place of birth and physical description. These aren’t true passenger lists, and only two are known to exist, but you’re in for quite a treat if your ancestor is named. The list for Beverly and Salem, Mass., covers 1798 to 1800; it’s transcribed in the New England Historical and Genealogical Register, volume 106. In Providence, RI, customs collector Jeremiah Olney continued recording aliens until 1808, even though the Alien Act had expired. The list is transcribed in my Rhode Island Passenger Lists (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) has two microfilms containing pre-1820 passenger lists: Work Projects Administration Transcript of Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, Louisiana, 1813-1849 (M2009), and Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1800-1882 (film M425; the lists are indexed in M360, Index to Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1800-1906).

3. Church records

A person arriving in his new land often would join a parish, carrying documents from his homeland to introduce himself to the congregation. Denominations used different terms for these papers, says Michael Teppel, author of American Passenger Arrival Records (Genealogical Publishing Co.): The Episcopal Church called them letters of transfer; the Congregational Church, dismissions; and the Society of Friends (Quakers), certificates of removal. Quaker monthly meeting records may contain information on new members, such as where they were from and when they immigrated. Lutheran churches kept records with similar data.

To find these documents, contact church archives covering the area where your ancestors lived, or turn to the national headquarters of the denomination for help finding the right repository.

4. Court records

Early Americans were a litigious bunch, so it’s not unlikely you’ll find evidence of an ancestor taking sides in a not-so-neighborly squabble, filing (or answering) a divorce petition or testifying in a criminal proceeding. NEHGS’ Dearborn says the resulting court documents are great sources of immigration information. One of his female ancestors returned to England, but her husband was later sued for nonpayment of her passage. Court records provided the wife’s homeland and parents’ names.

You’ll need to learn which court (for example, local, county or state) your ancestor may have visited, then find out where its records are kept. For help, see the court records section of the FHL research outline for that state (from the home page, click Guides, then Research Helps, then look for the state name). You’ll get an overview of each colony’s court system with links to catalog listings for the FHL’s print and microfilm resources. You also can use a reference such as the Red Book (Ancestry). Few Colonial court records are online, but you’ll find some here, and by exploring state archives websites.

Court dockets—schedules of cases—often appeared in Colonial newspapers. You can find some early court records transcribed in books; the court records chapter in Printed Sources (Ancestry) can guide you to those resources.

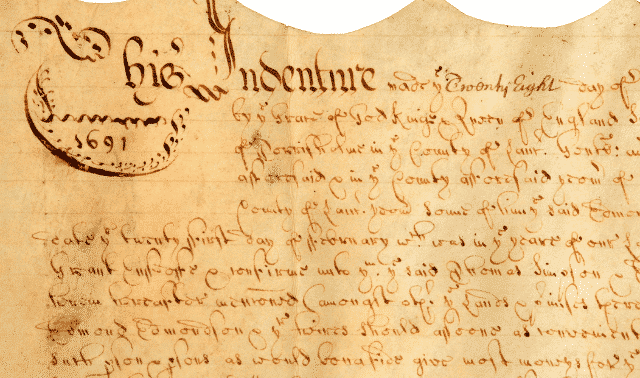

5. Land records

In the vast new continent, land was an obvious immigration incentive. In 17th-century Virginia, for example, individuals who sponsored (paid) immigrants’ passage received 50 acres. The land patent, called a headright, included the name of the sponsor, a description of the land and a list of people transported. The Library of Virginia has a free online database of Virginia land patents and grants beginning in 1623. These records through 1732 also are abstracted in Cavaliers and Pioneers compiled by Nell Marion Nugent (Genealogical Publishing Co.); it’s available on FHL microfilm.

Maryland made similar land grants, which you’ll find listed in The Early Settlers of Maryland by Guest Skordas (Genealogical Publishing Co.). Look for this book on FHL microfilm, too, along with its supplement. You’ll find transcribed volumes of Maryland’s provincial land records here.

In 1761, South Carolina’s general assembly offered land to Protestant refugees from Europe. Consult A Compilation of the Original Lists of Protestant Immigrants to South Carolina, 1763 to 1773 by Janie Revill (Genealogical Publishing Co.) for transcriptions of the original petitions, some of which provide a place of origin and ship name.

Land records from other areas also may include immigration information. Look for those covering your ancestor’s locale on the state archives website, in Printed Sources, and by searching Google (or another engine) on the colony name and colonial land records.

6. Naturalization records

In the British Colonial period, non-English immigrants were aliens and had to apply for citizenship. According to Loretto Dennis Szucs’ They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins (Ancestry), “Most citizenship records of the American Colonial period consist only of lists of oaths of allegiance signed by individuals as they disembarked from immigrant ships.” Although information varies, these records can include the passengers’ names, ship’s name and port of departure. Look for oaths in state archives and on FHL microfilm — run a keyword search of the state name and oaths of allegiance, or run a place search on the state and browse its naturalization records. You’ll find some oaths online by doing a Google search.

The first national naturalization act, passed in 1790, awarded citizenship to free whites over age 21 who’d lived in America two years or more. Interested individuals applied to common-law courts where they’d lived at least one year. If a person proved his moral character and swore allegiance, a judge would rule on the application. Married women and children under 21 came under the jurisdiction of their husbands and fathers, and children of unsuccessful applicants could apply on their own when they reached 21.

In 1795, residence requirements increased to five years and naturalization became a two-step process: First, an alien filed a declaration of intention, then three years later, a petition for admission. A stricter law in 1798 raised the residency requirement to 14 years, but Congress reversed it in 1802.

Applications usually include the full name of the immigrant, birthplace and date, arrival port and date, and residence. Locations of the original documents vary; some are at NARA facilities and others are at local courthouses.

7. Newspapers

You can dig up all kinds of hidden immigration details in Colonial-era newspapers: travelers’ thank-you announcements to captains for safe trips, advertisements for indentured servants, notices seeking missing immigrants. Printed marriage and death announcements some-times specified a country of birth. Even wanted ads for runaway slaves and Revolutionary War deserters might mention the absconded’s origins – in 1777, Lt. Samuel Snow of Rhode Island announced in the Providence Gazette that John Bayton of Ireland had deserted his company.

Old newspapers are often microfilmed – but not indexed – in local libraries and historical societies. If they cover your family’s locale, searchable online databases such as Early American Newspapers (available at subscribing libraries) and GenealogyBank can save you hours of scrolling. Search on a first and last name, then use keywords to narrow your hits.

8. Diaries and letters

Migrating diarists in the 17th through 19th centuries sometimes remarked upon their fellow travelers, as did those writing letters to family at home. Check your home (and relatives’) for such writings, then search manuscript collections at libraries and historical archives. Use the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections to find likely repositories: Enter your ancestor’s name (choose Personal Name from the drop-down menu), a geographic name or a subject. Read the About Searching Manuscripts page before you begin. ProQuest’s Archives USA database, available through many public and university libraries, also catalogs manuscript collections, and peruse Laura Arksey’s American Diaries: An Annotated Bibliography of Published American Diaries and Journals (Gale Group).

Following these crumbs to your ancestral homeland isn’t for the birds. Researching your ancestors’ early arrivals will bring you back to their first steps onto American soil – then you can start looking overseas for these intrepid early travelers. Who knows what you can find after that?

A version of this article appeared in the July 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.