“Missing in Action” (MIA) is a casualty classification for servicemembers who are reported missing during wartime. The classification reflects a deeper, long-standing military concern: identifying and accounting for the fallen. The term “missing” for “not present or found, absent” dates to the 1520s, but the military sense of “not present after a battle but not known to have been killed or captured” first came into use in 1845.

Unlike those classified as KIA (killed in action), individuals reported as MIA don’t often have definitive death records. More often they are presumed deceased.

If one of your family members was deemed MIA, finding records about their service can be difficult. Here’s how genealogists can learn more about their MIA relatives.

Historical Context: Wars, Records, and Reporting Practices

Evolving Casualty Reporting

Records for finding MIA servicemembers prior to the 20th century are often sparse due to inconsistent recordkeeping practices of the time. Casualty reporting started to become more formalized during the Civil War, increasing public awareness of the human cost of war both on and off the battlefield. According to the Congressional Research Service, casualty reports before World War I typically excluded individuals classified as missing unless they were later confirmed dead or returned. Over time, the processes for identifying and classifying casualties evolved—especially as wars became more global and military recordkeeping grew more centralized and systematic.

Military Units, Theaters of Operation, and Casualty Policies

Understanding a servicemember’s unit, the theater of operation they served in, and the casualty reporting policy of the time is critical. These determine which records might exist and how a missing status was reported or reclassified.

For instance, airmen lost in Europe during WWII may appear in Missing Air Crew Reports (MACRs), while Pacific Theater losses may fall under the Navy’s Air Accident Reports (AAR) casualty reports. Terms like “absent,” “AWOL,” “presumed lost,” or “unaccounted for” could all reflect MIA cases depending on context.

Pre-20th-Century Conflicts

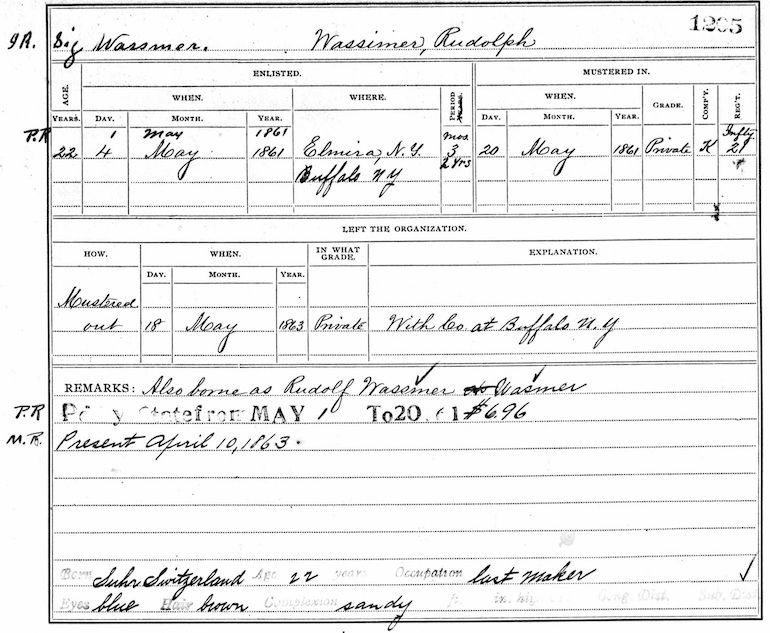

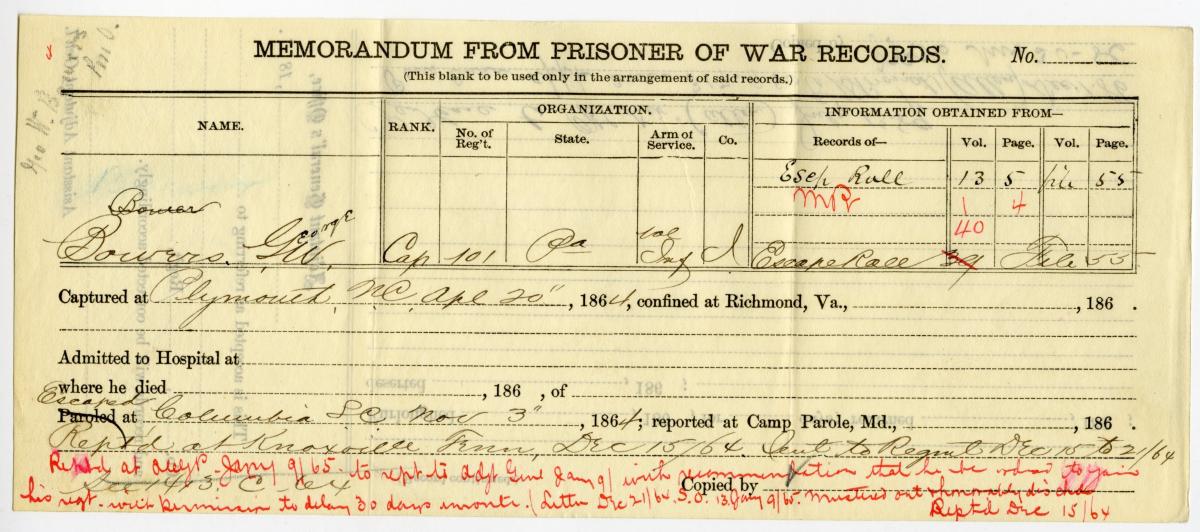

Records for MIA servicemembers in early American wars are limited due to informal and inconsistent recordkeeping practices of the time. For conflicts such as the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Civil War, muster rolls and unit histories are often the most informative sources. However, it’s important to understand that individuals who were absent from these rolls were frequently labeled using terms like absent without leave (AWOL), deserted, or unaccounted for, rather than officially classified as MIA.

This creates additional challenges, as servicemembers who were missing due to injury, death, or capture might have been presumed to have deserted. Conversely, someone presumed dead might have actually survived, gone AWOL, and later been captured and court-martialed. To clarify these cases, pension files, court-martial records, and post-war testimony files can be invaluable for genealogists trying to determine what truly happened.

Compiled military service records (CMSRs) and muster cards/rolls may list individuals as absent or missing, often also defaulted to AWOL or deserted. CMSRs are created from the original muster and pay rolls, regimental returns, and more military service records. NARA holds CMSRs for volunteer soldiers from the Revolutionary war through the Philippine Insurrection. The indexes to these records for the War of 1812, Early Indian Wars, Mexican War, Civil War, and the Spanish-American War have been digitized are available through subscription site Ancestry.com and Fold3.com.

Pension files and court-martial records can both clarify misclassification. (For example: a presumed deserter was later found to have been killed, captured or missing.) NARA houses the historical records U.S. Army court-martial case files from 1809 to 1917 in its Washington, D.C. building under Entry PC-29 15 of Record Group 153. FamilySearch has digitized the register (an index) for these records between 1809 and 1890 as “Registers of the records of the proceedings of the U.S. Army General courts-martial, 1809-1890.” In some cases, Widows Pension Files (and applications) can also contain information about a soldier that went missing as their dependents may have filed for support.

Official Records (OR) and Reports of the Civil War, officially titled The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies is a 128-volume, comprehensive publication of the official actions and reports submitted during the Civil War. Many reports include statistical and regimental information about missing servicemembers during the war. It is freely searchable on HathiTrust.

Unit histories, published for small units or regiments, may include lists of servicemembers that were killed in action, missing, or presumed dead. Many of these books are available on Google Books, HathiTrust and Archive.org. Search WorldCat.org to find more relevant titles and locate them in public libraries.

After the Civil War, humanitarian Clara Barton set up the Missing Soldiers Office in her boarding house in Washington, D.C. She received over 63,000 requests for help and was able to determine the fate of over 22,000 soldiers whose families requested information on their missing loved ones from her.

Though she was unable to identify all of the missing, throughout her three-year search after the Civil War, Barton and a team of clerks published the “rolls of missing men” comprised of those Barton couldn’t find. This led to Clara Barton’s Rolls of Missing Men, published in five increments. The contents of those rolls have been compiled into a searchable database by the National Museum of Civil War Medicine.

20th Century to Present

After the turn of the century, military recordkeeping practices improved significantly. For MIA cases during and after World War I, more-comprehensive documentation is available.

World War I

Researching an individual who served in World War I can be challenging due to the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center that destroyed US Army personnel files created between 1912 to 1963. Fortunately, Navy and Marine Corps personnel files were not affected. While the fire has left a gap in available service records, it is possible to fill in the missing details using alternative sources.

It is also important to note that National Guard records are not federal records and exist in the custody of state repositories. The National Guard of New York’s records have been digitized and published on Fold3.

The US World War I Centennial Commission’s “Doughboy MIA Database 1917-1920” is a freely searchable database of all known US servicemembers classified as MIA from World War I. The website’s Doughboy MIA section provides additional context and resources, including a list of all the recoveries made since 1934.

In NARA’s World War I research guide, Mitchell Yockelson, military historian and archivist at NARA, states, “Documentation on enlisted personnel is more difficult to locate among the records than that for officers. The best places to look are the correspondence and special orders in the Records of U.S. Army Mobile Units, 1821-1942 (Record Group 391).” A finding aid for this record group is available on NARA’s website.

Another overlooked source is NARA’s M930 publication, available on subscription site Fold3 as “US, WWI Military Cablegrams – AEF and War Dept, 1917-1919.” This publication includes cablegrams exchanged between the General Headquarters, American Expeditionary Forces, and the War Department during World War I. Many of the cablegrams include information on the last know location of servicemembers who were missing.

Similarly, details on MIA servicemembers can also be found in the US Army and Army Air Force’s Morning Reports, which are daily details of a military unit’s status. NARA’s collecting of morning reports has been digitized as “US, Morning Reports, 1912-1939” on Fold3.

Additionally, look for unit histories, eyewitness reports, and rosters. Casualty reports and other military records may exist at the state level via adjutant generals or state archives.

For British, Australian, Canadian and South African MIA servicemembers who served in World War I, Fold3 has published the index database of the Joint War Organization’s Enquiries: Missing, Wounded and Dead Personnel, 1914-1918.

World War II

IDPFs (individual deceased personnel files) are key for identifying remains and documenting cases. Some IDPFs for the years 1939 to 1959 are digitally available on NARA’s catalog, including for some servicemembers classified as MIA.

Missing airmen may be noted in MACRs (missing air crew reports) and AARs (aircraft accident reports).

- MACRs were compiled by the US Army Air Forces to record relevant facts of the last known circumstances of missing air crews. Fold3 has digitized NARA’s M1380 collection of US MACRs for WWII, 1942–1947, which contains over 16,000 case files of MACRs and related records.

- AARs were compiled by the US Navy and Marines as a record of operational losses. Presently, the collection covers the period 1920 to December 1969 and generally does not report on combat losses. Access to the AARs is limited due to restricted information contained within the reports. However, reports prior to July 1955 are “fully releasable.” In order to obtain a copy of the report, it’s necessary to know the type of aircraft and the date of the accident, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

Aviation Archaeological Investigation & Research (AviationArchaeology.com/AAIR) has acquired and digitized (in indexed databases) over 2,000 micofilm reels of all the government’s military accident reports and aircraft record cards on their website. AAIR has over 150,000 accident reports on file and researchers can order them through their website.

Collections from NARA’s record group 407 and record group 24, titled respectively as “US, WWII Army and Air Force Casualty List, 1946” and “US, WWII Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Casualty List, 1946,” are online through Fold3 and are honor lists of dead and missing servicemembers. Both of these databases are also available on Ancestry.com. Ancestry.com also has a database of “U.S., World War II Military Personnel Missing In Action or Lost At Sea, 1941-1946.”

Ancestry.com’s “U.S., Navy Casualties Books, 1776-1941” includes a list of lost and wrecked ships from 1801-1941.

Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA)’s Missing Personnel Database allows you to search by name, conflict, branch, and accounting status beginning with World War II.

In a similar way, the American Battle Monuments Commission’s Burial and Memorialization Directory honors those buried overseas or listed on Walls of the Missing. Entries include individuals classified as Missing in Action beginning with World War I, providing details about their service, date of loss, and memorial location.

Post-WWII Conflicts

NARA’s Access to Archival Databases (AAD) site has free, searchable index databases for a variety of later 20th-century conflicts which include information on servicemembers declared as MIA, including:

- The “Defense Casualty Analysis System (DCAS) Files, created, ca. 2001 – 3/16/2009, documenting the period 6/28/1950 – 12/31/2006” database was created by the Department of Defense. It records “all military personnel casualties that occurred between 1950 and 2006,” including that of individuals “who were missing in action or prisoners of war in either the Korean War or the Vietnam War.”

- “Records on Military Personnel Who Died, Were Missing in Action or Prisoners of War as a Result of the Vietnam War, created, 1/20/1967 – 12/1998, documenting the period 6/8/1956 – 1/21/1998.” This series contains records of U.S. military officers and soldiers who died or who were missing in action or prisoners of war in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War.

IDPFs can also be requested for post-WWII conflicts. Relatives can call their relevant Service Casualty office and request an IDPF for their MIA relative. The IDPF may contain information such as death certificates, letters, eye-witness reports, Missing Aircraft Crew Report (MACR), Aircraft Accident Report (AAR), maps, and more information.

Another standard record, the OMPF (official military personnel file) contains details of service. These are accessible to the public 62 years after a member’s service ended, though many were lost in a 1973 archive fire.

Also check the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA)’s Missing Personnel Database and the American Battle Monuments Commission’s Burial and Memorialization Directory as mentioned above.

Alternative Sources

If you can’t find military records about your MIA relatives, look for information about them in:

- Newspapers: Local papers often reporting on missing servicemembers from the surrounding area.

- Local archives & regimental associations: Town clerks, historical societies, and veteran groups may hold overlooked records on MIA individuals.

- Testimonies: Letters from fellow servicemembers or wartime memoirs can provide context or even eyewitness accounts.

Final Notes: Continuing the Search

Even today, remains from past conflicts are still being identified and returned to families. Genealogists often play a vital role in this process, aiding in identification through genetic genealogy research.

If you believe that a relative is still unaccounted for, consider contacting:

- The relevant Service Casualty Office

- The DPAA for case updates

- NARA or a professional genealogy for assistance requesting records