Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

In the view of filmmaker Ken Burns, The Vietnam War—his documentary with codirector Lynn Novick—isn’t meant to provide answers about a war that helped usher America into an era of political and social turmoil. Instead, it raises questions.

Following in the steps of Burns’ previous documentaries on World War II and the Civil War, The Vietnam War hits hard with intense footage and emotional accounts from American military and their families, protesters, and Vietnamese combatants and civilians. In 10 parts and 18 hours, the film shares a range of perspectives from witnesses to a complicated, chaotic history.

Vietnam War History

The United States had backed Vietnam’s Communist Viet Minh coalition against Japanese invaders during World War II, then switched sides as Viet Minh fought France for independence in the First Indochina War.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1954, a now-independent Vietnam was divided into Communist North and antiCommunist South. Communist-sympathizing guerrillas called Viet Cong launched attacks in the South in the late 1950s, prompting the United States to send military advisors to South Vietnam. More troops followed—23,300 by 1964—as the North lent support to the Viet Cong. Escalation continued until 1968, with 536,100 troops in Vietnam. The number decreased under President Richard Nixon’s “Vietnamization” plan to hand over the conflict (technically the correct term for it, as the United States never declared war) to South Vietnam. Combat troops were withdrawn in 1973, though the war continued until South Vietnamese capital Saigon fell in 1975.

A total of 2.7 million Americans served, at 22 years old on average. Between 7,500 and 11,000 were women. About 300,000 were wounded, and 58,000 killed. Injuries disabled tens of thousands. More than 1,200 are unaccounted for to this day.

Troops returned home with little to show for their sacrifice, many having witnessed the unimaginable, to a public disgusted with the war and distrustful of the US government. Some struggled to adjust to civilian life and suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. The war still causes debates: Was it necessary or not? What went wrong?

ADVERTISEMENT

No wonder so many veterans didn’t talk about their wartime experiences, and so many families didn’t ask—leaving siblings and children to wonder, years later, what their loved ones had been through. Start discovering the answers with these strategies for researching your relatives’ Vietnam War service.

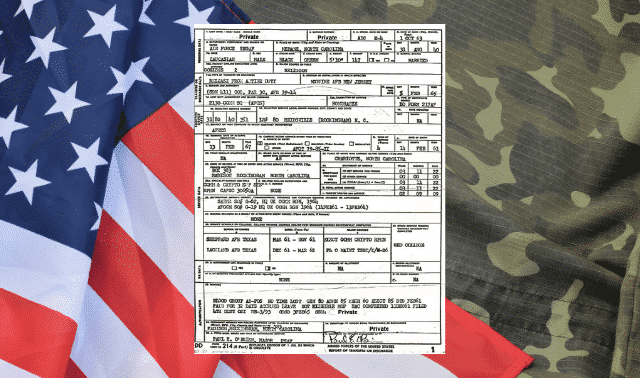

Finding Vietnam War Discharge and Service Records

Like any genealogy project, this one starts at home. Search for letters, discharge papers and photos relating to your veteran. Talk to him or her if possible—see tips below from The Vietnam War senior producer Sarah Botstein. Try to learn basic details such as whether the person was drafted or volunteered, the service number, dates of service, training locations, when deployed, unit served in, and places stationed. Read about the war to familiarize yourself with locations, operations and events mentioned in records.

Next, request military personnel records from the National Archives’ National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis. These can include Department of Defense form 214 (called the DD 214 or Separation Documents, which record a discharge), personnel records from the person’s Official Military Personnel File, and medical records. Termed “nonarchival” because they document people separated from the military less than 62 years ago, these records fall under restrictions to protect veterans’ privacy.

Requestors must be the service member him- or herself, or if deceased, a spouse who hasn’t remarried, a parent, a child or a sibling. Follow these instructions in making your request. Provide as much identifying information as you know, including name, service number, SSN, and branch and dates of service. If you’re requesting a deceased veteran’s records, you’ll need to supply proof of death, such as a death certificate or obituary, and sign an affidavit saying you’re next of kin.

NPRC will initially send the DD 214, which provides the person’s service number, information about service dates, promotions and reductions, awards and commendations, and medical treatment. You can send NPRC a follow-up request for more information, which might include leave papers, identification card applications, and clothing issuances.

You may have heard that many 20th-century military records were destroyed in a 1973 fire at the NPRC. The fire affected files of those discharged before 1964, so chances are your Vietnam veteran’s records survived. If not, you can request a Certificate of Service with basic information from other records. Read more about the fire and damaged records.

Like veterans of the World Wars, those returning from Vietnam could register their discharge at a local courthouse—a helpful substitute for a missing DD 214. You may need to visit the courthouse or send a request, but you might find discharges among digitized court records at FamilySearch. Search the online catalog for the county and look under the court records heading. The catalog entry will link to digitized records, if they exist. Luckily, an index book listing my dad’s discharge in 1969 is among the site’s digitized county court records. I’ll need to request a copy of the record from the courthouse.

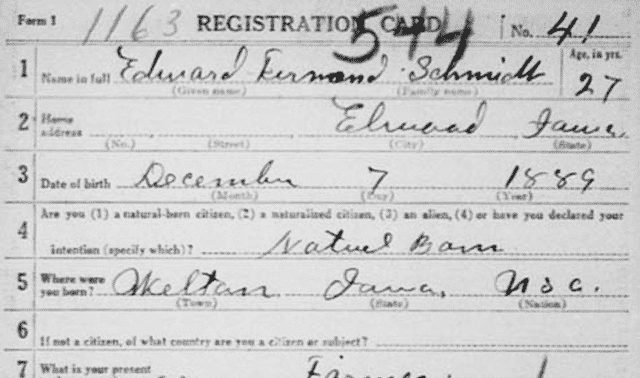

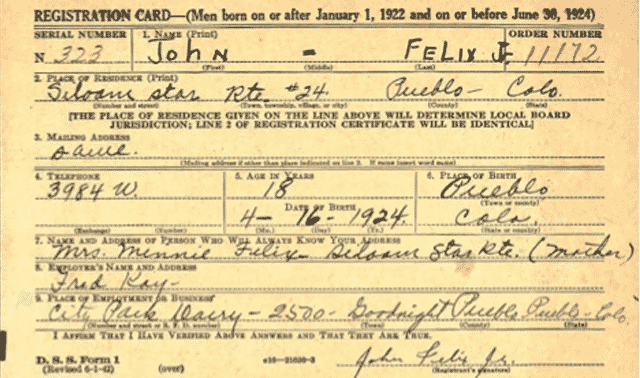

Researching Military Draft Records

The NPRC also has post-WWII through Vietnam-era Selective Service (draft) records for men born before 1960. The draft registration card (SSS Form 1) may contain information such as name, Selective Service registration number, age, date and place of birth, ethnicity, place of residence at the time of registration and basic physical description.

These details might sound ho-hum, but there’s more to be found for draftees who appealed their selection: The classification history (SSS Form 102) may contain name, date of birth, classification, date of mailing notice, date of appeal to the board, date and results of the armed forces physical exam, entry into active duty or civilian work in lieu of induction, date of separation from active duty or civilian work, and general remarks. You can order copies of these records for a fee.

Learning About Casualties and the Missing

If your veteran was injured or killed in the war, search for casualties online in National Archives databases. Datasets include Records on Military Personnel Who Died, Were Missing in Action or Prisoners of War as a Result of the Vietnam War (the same databases are on genealogy sites such as the free Access Genealogy). Also see state-level casualty lists.

Burials in national military cemeteries are recorded in the VA’s Nationwide Gravesite Locator. The names of those who died in service are engraved in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall in Washington, DC. Visiting the memorial to make a rubbing of your loved one’s name is a powerful experience (you also can request a rubbing by mail). Search Fold3’s life-size photo re-creation of the memorial for free; click a person’s name in your search results to view the name on the wall and if available, details such as the casualty location and date.

For information on the National Archives’ records related to POWs and those reported MIA, see the National Archives’ finding aid. The 2,504 individuals who went MIA are named in the American Battle Monuments Commission website’s searchable database and on the commission’s Tablets of the Missing memorial in Honolulu.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency is responsible for determining the fate of missing personnel and identifying remains of the dead. The agency’s website states it’s “not authorized to expend resources for requests outside the scope of our mission,” so it doesn’t respond to research requests. You can see its list of those still missing online.

Vietnam Military Service Awards

Awards are noted on the DD 214. (The Vietnam Service Award was given to all who were honorably discharged, so you won’t find related specific details.) You also can search the National Archives’ database, Records of Awards and Decorations of Honor During the Vietnam War. The same data is in the Ancestry.com database Vietnam War, Awards and Decorations of Honor, 1965–1972. The source files, from National Archives’ Record Group 472, make up Fold3’s free Vietnam Service Awards collection.

Try searching for the person’s name. But because many awards were made to entire units, it’s a better bet to run a keyword search for the battalion, brigade or division, or for places where the person was stationed. You might find the date of the award and a description of the action for which it was given.

For example, my dad was in the 14th Engineer Battalion (Combat), and a keyword search for 14th engineer returns long memos describing the battalion’s meritorious service in building bases and bridges, maintaining roads, constructing airfields and other duties. Most occurred before my dad’s tour, but the documents tell me the kind of work he did. You can see pictures of Vietnam medals and link to information about them.

Photos and Documents

Fold3 has photos of personnel, locations and more, organized by military branch. Use the research you’ve gathered for clues, and search for the person’s name, company, service unit, locations and more. My dad had mentioned being at FSB (fire support base) Nancy, and I found several photos. Googling FSB Nancy also led me to a YouTube video of the base from a helicopter.

In her research for The Vietnam War, Botstein used Texas Tech University’s online Virtual Vietnam Archive of more than 4 million pages of scanned documents, photos and recordings. You’ll find after-action or “lessons learned” reports, news articles, newsletters of veterans groups, letters, finding aids for Vietnam-related collections, photos and footage of troops, memoirs, oral histories, maps, pictures of insignia and more. (The website Records of War Vietnam lets you browse many of Texas Tech’s reports and other resources by service branch and unit.) Most items are digitized on the site, but some copyrighted items, such as the Pacific Stars and Stripes newspaper, are available only offline by request.

Also try the National Archives online catalog. It’s unlikely you’ll find someone by name, but you may find correspondence, records and photos relating to your relative’s service. My search on Vietnam engineers led to identified photos of Marine Corps engineers, a glossary of jargon troops used and more. Adding 14th brought up catalog records for 14th Engineer Battalion operational reports; I’d need to contact the archives to request copies.

You can use filters next to your search results to see only photos, or select “archival descriptions with digital objects” to view only items that are digitized.

Oral Histories

Firsthand accounts from those who experienced the same things your relative did can give you insight into his story. Texas Tech makes its oral histories available through the Vietnam Center and Archive Oral History Project. Also explore the Library of Congress’ Veterans Oral History Project. Search there by keyword or browse by conflict, branch and other terms. At the US Army Center for Military History, select Archival Material to hear selections from interviews. This site also has photos and downloadable documents with information on the war.

Vietnam Veterans Groups and Websites

Several sites, such as The American War Library and VetFriends have message boards where veterans reminisce and ask about buddies. You could search for mentions of your veteran’s name or military unit, or you could post a request for any memories of him.

Find veterans groups online and on Facebook by searching for Vietnam and the unit your relative served with. I found a page for the 14th Combat Engineer Battalion Association with issues of the Swampy Sentinel, a typewritten newsletter published by battalion members serving in Vietnam. They included a breakdown of activities by company. Your efforts will bring you a lot closer to understanding the experiences of your loved one.

Tips for Interviewing a Vietnam Veteran

How do you even begin to approach the topic of Vietnam with a veteran when you’ve never really talked about it before? Remember that just because someone hasn’t talked about it doesn’t mean she’s unwilling—some people don’t share until they’re asked. And if the time hasn’t been right in the past, it may be now.

You’ll need to broach the topic to have the veteran sign a DD 214 request. Try bringing up a book you’ve read or watching The Vietnam War with the veteran.

“I would recommend not watching the film alone,” says senior producer Sarah Botstein. “Watch it with someone who was alive during that time. It’ll definitely get a conversation started.” Then ask the person if he or she minds sharing some memories with you—whether now or during a later visit.

Before you talk, “learn the history—not just specific to that person,” Botstein says. Use the resources in this article to gather information and help you prepare your questions. Also consult this guide for some interview tips.

Botstein spends hours talking with veterans to establish a comfort level before filming. You already know your veteran (and you’re not going on TV) so you can build rapport by covering the basics first. “Start chronologically with the facts,” Botstein recommends. Ask the person’s name, birth date, hometown, where he went to high school and college (if applicable), and reason for entering military service. Work into the topic by asking about training, feelings in the first days of service, thoughts about the new environment, the food, base life, and keeping in touch with family.

Then you can ask the person about his assignments, fellow soldiers who stand out in memory, and combat experiences. If you have details on where the person served or operations he was part of, you can ask specifically for memories of those places and events. Ask if the person has any photos or other mementos he can show you, as well.

Don’t interrupt to ask for more details about a memory. Instead, make a note and ask after the person has finished his thought. Be patient during silent pauses while the person tries to recall long-ago details. There’s no need to jump in right away if he gets emotional; instead, give him a few moments to regain composure. You also can ask if he’d like to switch topics for awhile.

Take notes, but you’ll also want to preserve the stories by recording the interview. Use a digital recorder or smartphone app such as Hi-Q or Easy Voice Recorder (Android) or Just Press Record (iOS). Practice with your equipment ahead of time, and remember extra batteries or charging cords.

Vietnam War Websites and Books

- How to Read a DD 214

- National Archives: Vietnam War Records

- Online Vietnam War Indexes and Records

- Records of War Vietnam

- Request Veterans Records

- US Air Force Historical Research Agency

- US Coast Guard Historian’s Office

- US Marine Corps History Division

- US Naval History & Heritage Command

- The Vietnam Center and Archives at Texas Tech University

- The Vietnam War: A Film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick

- Vietnam War Overview

- Vietnam War Commemoration Maps

- Vietnam War Timeline

- The Girl in the Picture: The Story of Kim Phuc, the Photograph, and the Vietnam War by Denise Chong (Penguin)

- The Killing Zone: My Life in the Vietnam War (reissue ed.) by Frederick Downs Jr. (Norton & Co.)

- Vietnam: A History by Stanley Karnow (Penguin)

- Vietnam: A History of the War by Russell Freedman (Holiday House)

- Vietnam: The Ten Thousand Day War by Michael MacLear (St. Martin’s Press)

- The Vietnam War: An Intimate History by Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns (Knopf)

- A Vietnam War Reader by Michael H. Hunt (University of North Carolina Press)

A version of this article appeared in the September 2017 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Last Updated: February 2023

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT