Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Think of all the paperwork you generate at your job: countless memos, reports, requisitions, invoices and more. But that’s just the beginning. Every employee requires a small mountain of human-resources forms and files, from pay stubs and accounting records, Social Security and unemployment documents, to insurance and benefits rigmarole. You might take up some ink in employee newsletters, annual reports and other industry publications, as well. A job is a paperwork-producing monster, gobbling up trees and (these days) bits and bytes like the shark from Jaws.

Your ancestors’ occupations may have been simpler—“mill worker” or “miner,” say, rather than “assistant sub-director of inventory maximization analysis”—and the resulting paperwork less onerous and Byzantine, but their jobs still generated records. And buried within those records might be the clues you need to break through the brick walls in your research.

True, most of the memos and such cranked out at your job—or your ancestors’—lack any obvious genealogical value. But family historians often struggle simply to uncover an ancestor’s name and to prove he or she existed. Some descendant of yours might find just what she needs in your memo explaining how losing the Maxcorp account wasn’t really your fault.

Moreover, job-related paperwork is full of dates and places—exactly what a savvy genealogist needs to follow up in more-conventional records. If you found that your great-grandfather built carriages in Cincinnati in 1880, for instance, you’d know where and when to look for him in the census and city directories. You could guess that your grandfather (his son), who was born about that time, might have a birth record in Cincinnati.

But occupational records can unlock more than mere clues. Employment applications can include key dates and places of previous employment and education; entries about hobbies; and various personal data, such as religion and marital status, that employers aren’t allowed to ask anymore. Apprenticeship and indenture paperwork typically included the names of a young worker’s parents. The US Railroad Retirement Board’s pension records contain copies of employees’ death certificates. If your ancestor was licensed as a barber in Arkansas, the Arkansas State Archives may have his photograph.

Where to look for clues to your ancestors’ job

You might think that your ancestors probably didn’t have jobs in today’s sense. Farmers, after all, may have generated land records instead of payroll listings or union memberships. But the notion that most Americans in yesteryear were farmers is a misconception: By 1880, more than half of working Americans already were engaged in something other than agriculture. So odds are good that your early 20th-century or even late 19th-century ancestor had an occupation that left a paper trail for you to follow.

To start delving into your ancestors’ occupational records, you have to know what they did for a living. That can seem like a classic catch-22: If an ancestor is a “brick wall” in your research, how the heck are you supposed to find out about his occupation? But uncovering an ancestor’s employment may be simpler than you think.

Family papers

As with any other genealogical search, your hunt for occupational records should start at home. Look through letters, files and old family papers: Your ancestor may have brought job-related paperwork home, or a letter may contain an offhand remark about Great-grandpa’s promotion at the plant. You could come across old paycheck stubs, bankbook entries or account books. Seek out anything related to pensions in particular. Scan for clues in old family photos, as well: I never knew about my grandfather’s stint as an autoworker, for example, until my cousin shared a photo of him on the assembly line, building Model-A Fords.

Family interviews

Interview older family members for leads. Grandma may be more likely to remember where her father went off to work every day than the answers to other questions you’ve posed to her. Family lore or handed-down family histories might tell you that an ancestor was a doctor or a minister—which can lead you to more-specific information in professional archives.

City directories

Next, hit the library and the internet. If you can find an ancestor in a city directory, the listing usually will give both his occupation and employer. For instance, the entry for Robert H. Johnson in the 1894 Great Barrington, Mass., directory includes this information: “porter, E. Hollister & Son.” As this example shows, your ancestor didn’t have to live in a major metropolitan area to be listed in a city directory. Search the FamilySearch Wiki to learn more about where to find city directories. Ancestry.com has put city directories from across the country online, so you quickly can search for signs of your kin. For more on city directories and where to find them, see the website City Directories of the USA.

Town and county history books

Various types of town and county history books, including the forerunners of today’s Who’s Who volumes, often mentioned what local leading lights (and even some lesser lights) did for a living. You can find these publications in your ancestral hometown’s library or historical society, in larger public libraries and in genealogy collections such as those at the Newberry Library in Chicago and the Sutro Library in San Francisco. Many such books have been microfilmed by the FHL: Your Wichita, Kan., ancestors, for example, might be mentioned—along with their occupations—in the two-volume History of Wichita and Sedgwick County, Kansas: Past and Present, Including an Account of the Cities, Towns and Villages of the County edited by Orsemus Hills Bentley. HeritageQuest Online’s Genealogy & Local History Collection—accessible at subscribing libraries as well as Ancestry.com’s Family and Local Histories Collection (subscription required)—lets you search many such books, as well as city directories. Specify place, surname and even keywords such as baker or dentist to learn, for example, that Henry Riggs worked as a civil engineer in Ann Arbor, Mich., in 1891—according to Ann Arbor: The First Hundred Years by O.W. Stephenson.

Newspapers

Newspapers also can tell you an ancestor’s occupation. Obituaries, of course, usually detail the deceased’s employment history. But by searching your ancestor’s hometown paper, you also might find your answer in business articles, legal notices and even advertisements. If you get tired of scrolling through microfilmed newspapers, Ancestry.com’s Historical Newspaper Collection lets you search for ancestors online in a single periodical or dozens at once. A search of the Adams Sentinel in Gettysburg, Pa., for instance, would reveal that William N. Irvine was a lawyer—he made the paper July 27, 1835, when he was named prosecuting attorney of his county.

How to find out more from occupational records

Once you’ve learned what an ancestor did for a living, what can you find out about him from occupational records? The answer varies greatly, depending on his line of work. Some careers of yesteryear simply generated more paperwork than others. Here’s a look at some of the genealogical goodies you might uncover, based on your ancestor’s occupation:

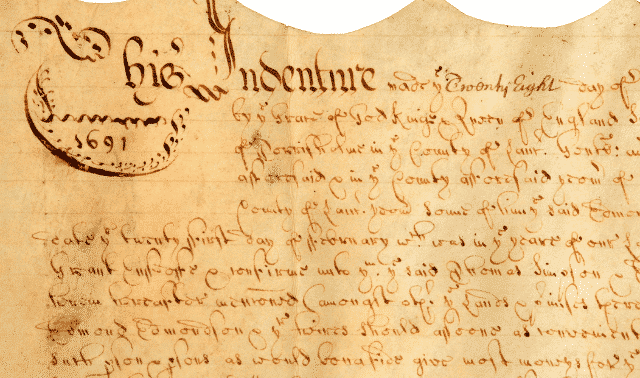

Apprenticeships and indentured servitude

Among the oldest occupational records you’re likely to find are those for two kinds of employment almost unheard of today: apprenticeships, in which a young person was bound to a master to learn a trade, and indentured servitude, in which a person was committed to working off a debt, such as payment for passage to America. The two often overlap, and in Colonial America the agreement apprenticing a youth was called an indenture. These documents are valuable for genealogy because they had to be signed by the apprentice’s parent or guardian. Most apprentices were teenage boys, and they were obligated to work at their trade until age 21. The term of an apprenticeship can be used to estimate an apprenticed ancestor’s age, by subtracting the term from 21.

Typically, apprentice ship records were made at the local level, but many of these documents have since migrated into state archives and historical societies. If you have English ancestors, you might be able to use apprenticeship records to trace your kin back to the old country; the National Archives has a helpful guide to these resources. For early American ancestors, the FHL has collections of apprenticeship documents from Pennsylvania and Virginia. Ancestry offers a database of more than 8,000 Virginia apprentices from 1623 to 1800. Indenture records also can overlap with passenger records, as the most common type of indenture was payment for passage to America. State and local archives may hold indenture records, although these can take a bit of digging to find. The Pennsylvania State Archives, for instance, has two boxes labeled “Records of the Proprietary Government, Provincial Council, 1682 1776 — Miscellaneous Papers, 1664-1775,” among which a dedicated researcher could uncover the Oct. 31, 1765, agreement binding one Charles Carroll of Maryland to Richard McCallister.

Railroad

If your ancestor worked in railroading—as did some 2.25 million Americans in the early 1900s—you’re in luck. The spread of trains across the continent created an even more sprawling system of paperwork, much of which has been preserved.

If you know which company your ancestor worked for, you often can find surviving records in the company’s archives or in papers that have been donated to some repository. For example, the California State Railroad Museum Library in Sacramento, Calif. has employment cards from the Southern Pacific Railroad dating back to 1903. Chicago’s Newberry Library archives records from the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad Co. The Minnesota Historical Society holds the records of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific lines.

The South Suburban Genealogical Society in South Holland, Ill., has indexed nearly a million Pullman Co. records dating from 1900 to 1949 and covering 200,000 employees. Though the Pullman Collection isn’t open to the public, you can request a quick search for free using an online form. If they find an ancestor, the society will notify you within 6-8 weeks.

If your ancestor was a railroad company official, you might find him in The Biographical Directory of the Railway Officials of America, available in some libraries and archives, including the California State Railroad Museum.

The company your ancestor worked for may have merged with another railroad, requiring a sort of genealogical search of railroads’ corporate “family trees.” Moody’s Transportation Manual, found in most large libraries, can help, as can the Family Tree of North American Railroads.

Retirement records for ex-railroad employees represent another treasure trove. In fact, your ancestor’s Social Security number can help you determine whether he worked for the railroads in the first place: Until 1964, railroad employees were given special numbers, with the first three digits (ordinarily designating geographic area) falling between 700 and 729. The Social Security Death Index can give you a deceased ancestor’s Social Security number.

The Railroad Retirement Board will search its records for a fee. Searches are limited to the deceased, and your ancestor must have been working for a railroad after 1936. You may need to know the Social Security number in order to narrow the search adequately.

Labor union

Regardless of the industry, if your ancestor belonged to a labor union, you might find him in union records. Many of these are archived at Wayne State University in Detroit, home to the Walter P. Reuther Library. It maintains the archives of the United Auto Workers plus unions for government employees, teachers, farm workers, flight attendants and many others.

If your ancestor’s union records have been turned over to some other archive, you can track them down using the Library of Congress’ National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections (NUCMC), which indexes manuscripts of all sorts placed in repositories nationwide. Earlier catalogs are in print at major libraries; editions from 1986 to date are online at lcweb.loc.gov/coll/nucmc/nucmc.html. Besides union records, NUCMC should be a first stop for almost any kind of employment record you might be seeking — don’t let the term manuscript limit you.

Federal employees

In addition to union records, ancestors who worked for the government at some level likely left as much paperwork as you’d expect from any bureaucracy. You can find federal employees — both civilian and military — in The Official Register of the United States, a listing Uncle Sam first published in 1816, then every other year from 1817 to 1959. Major libraries and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) carry these handy volumes.

If your ancestor delivered mail for a living, read up on the history of the US Postal Service. NARA keeps records of postmaster appointments, which have been microfilmed on four rolls for pre-1832 appointments (publication M1131) and 145 rolls covering 1832 to 1971 (publication M841). Some amateur postal historians also have delved into postmasters past: Check out Jim Wheat’s Postmasters & Post Offices of Texas, 1846-1930 website. Many postmasters were actually postmistresses, so you might find your great-grandmother here, too.

On the local-government level, try historical societies and municipal archives for pensions of employees such as firefighters and police officers. Many major cities have archives dedicated to these public servants, such as the Los Angeles Fire Department Historical Archive. At Cyndi’s List, you’ll find more links for researching public employees.

Vocational license

Governments also generated records for all sorts of private occupations that required a license. As that Arkansas archive of barbers demonstrates, a wide variety of vocations had licenses over the years, from saloonkeepers to peddlers. Though you can’t count on finding photos in these files, license applications often asked for personal information—age, birth date, residence, previous residence, marital status, education—that can fill the blanks in your family tree.

Local governments granted most licenses, so you’ll find these files in municipal archives or historical societies. Some have been relocated to state repositories, so the Pennsylvania State Archives, for example, has tavern licenses from 1750 to 1855 and peddlers’ licenses from Philadelphia for 1820 to 1838. The federal government also issued some licenses, such as those for operators of marine vessels; these are stored in NARA’s regional offices.

Medicine

Ancestors with medical occupations also required licenses, of course. Licenses for doctors, dentists, nurses, pharmacists and the like typically were issued on the state level, and thus have wound up in state archives or historical societies. The Pennsylvania State Archives, for instance, keeps records for medical and dental licenses. Occasionally such licenses were issued municipally, so the St. Louis Board of Pharmacy, for example, has an archive covering 1893 to 1909. Some medical licenses slowly are being added to the vast trove of genealogical records available online: The Washington State Archives lets you browse records of more than 9,000 physicians licensed in that state.

You also can turn to national professional organizations, such as the American Medical Association (AMA), whose archives cover more than 350,000 physicians who practiced as early as 1804 (records before 1907 are not complete). The AMA’s records of physicians who died between 1864 and 1970 have been microfilmed by the FHL; the 237 reels include some Canadian doctors. The AMA also published a print directory of nearly 150,000 doctors who died between 1804 and 1929. For early physicians, you can consult American Physicians of the 19th Century, compiled from various medical journals by Charles A. O’Dell and available on microfilm from the FHL.

Similar volumes for dentists include America’s Dental Leaders and Who’s Who in American Dentistry. Your nearest dental school should have copies.

Depending on the locale, you might luck onto a regional directory of medical workers, such as the physicians, dentists and druggists directory for Minnesota and Wisconsin published in 1890 (available through the FHL).

Don’t overlook any aspect of the medical realm when seeking occupational records. The county clerk’s office in DeKalb County, Mo., for instance, keeps licenses for chiropractors in 1927 and for embalmers from 1912 through 1924.

Law

Attorney ancestors likewise had to be licensed to practice law, so they may have records in the archives of the American Bar Association or their state’s bar association. But you won’t necessarily have to dig into dusty boxes to find your lawyer ancestors: Most states and many counties and cities have books on the local legal profession at various points in history, typically titled The Bench and Bar of (locality name). These may cover attorneys and judges from years past, with their dates of death and ages at death. Public libraries near your ancestral stomping grounds are the best bets for consulting such volumes: If your great-grandfather practiced law in Boone County, Mo., for example, you might find him in The Bench and Bar of Boone County, Missouri, available at the Kansas City Public Library. If you live near a law school, you also can try its law library.

If you’re not sure where Great-grandpa practiced law, consult the Martindale-Hubbell Law Directory. This listing of American attorneys began publication in the 1860s as Martindale’s American Law Directory. Your nearest law library may have old editions.

Finance

Another records-rich profession is banking. If your ancestor was a banker, you may be able to find him in a banking directory. In England, directories of bankers go back all the way to 1677. On this side of the Atlantic, the American Bankers Association published The Bankers’ Directory in 1917, with almost 1,700 pages of listings. Other directories date as far back as 1800.

Clerical

You can learn a lot about clerical kin from the archives of their denomination. Many denominations published directories of their ministers, as well as in-depth accounts of ministerial meetings and progress spreading the word out West. Certain denominations also published newspapers, which recorded ministerial milestones and obituaries.

Church histories can offer genealogical blessings, too. I researched my great-great-grandfather, the Rev. Robert Robinson Dickinson, in a book called The History of Methodism in Alabama and West Florida. I found references to his 1840 admission to the ministry, and was able to trace his movements across the area as he was assigned to new churches. Finally, I found an obituary, which read in part, “Meek, guileless, and full of tenderness, he was in all respects a Christian gentleman. His presiding elder, who visited him during the afternoon prior to his death, said, ‘He had been in peace from first to told me he had been in peace from first to last during his illness, and that not a cloud darkened his sky.’” I could add all that to our family history simply because of my great-great-grandfather’s “job.”

Education

You’ll often find records of educator ancestors in the archives of the school district or of the college or university where they taught. Many of these schools have long histories—Harvard College, after all, was founded way back in 1636. A published history of the school might mention your ancestor; Harvard has the Harvard Book, a two-volume work published in 1875 that contains history, anecdotes and rare campus photos. And don’t overlook those handy volumes that most schools publish every year—their yearbooks. Though aimed at students, these often include photos and other information on employees.

What if my ancestor’s company is out of business?

Sometimes your quest for occupational records will wind up at what seems to be a dead end. The most obvious challenge in researching your ancestor’s employment arises when the employer seemingly is no more. But even bygone companies sometimes can be traced—their papers may have been archived or passed along to some successor company.

To see if a company is still in business, check your library for Dun & Bradstreet’s Million Dollar Directory, which lists all the country’s large corporations. This directory is also available as a subscription database. Can’t find the company that employed your ancestor? It may have been absorbed by another enterprise or otherwise changed its identity. Check another Dun & Bradstreet directory, the three-volume America’s Corporate Families, which traces the “family trees” of 12,700 companies. You also can try tracing a seemingly defunct company through its stock, using the Robert D. Fisher Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities or the various Moody’s investor manuals for major industries. All these volumes can be found in the reference section of large libraries.

Other resources for following your family in corporate America include trade journals, association directories and published company histories. Check the business desk at your local library for these.

Today, of course, the internet makes it easy to investigate employers past and present. If your ancestor worked at Goldsmith’s department store in Memphis, a quick search will reveal that Federated Department Stores—parent of Macy’s—acquired the company in 1959. That could lead you to Macy’s website, which includes a detailed company history and timeline.

You can trace smaller companies using the same city directories—and their kin, business directories—that you used to find your ancestor’s job. Think of these as the precursors of the yellow pages. They can help you follow a business from year to year, location to location. If Hotchkiss Buggywhips at 203 E. Main St. suddenly vanishes, but the directory now shows a Hotchkiss Auto Parts at the same address, there’s probably a connection.

The bottom line is that persistence pays in researching your ancestors’ occupational records. Don’t give up, and don’t be too quick to assume that the sort of job you’re investigating doesn’t have any associated paperwork.

Even ancestors who worked in the “oldest profession” may have generated occupational records: Philadelphia’s Guardians of the Poor complied a detailed directory of the city’s prostitutes in 1863. This register, now in the city archives, includes facts such as name; age; birthplace; length of time in Philadelphia; reason for entering the United States, if an immigrant; literacy level; marital status; number of children, their ages, present location and whether or not they’re legitimate; reason for becoming a prostitute; age first diseased; wages; parents’ occupations; and more.

If only all occupations had records that were so genealogically useful!

A version of this article appeared in the April 2005 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Updated: August 2021