Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

It’s often a pain to file your individual taxes with the government (unless you end up with a refund!). But the fact that various levels of government in the United States have kept records of our taxes turns pain into pleasure for genealogists: Tax records let you anchor your ancestors in a particular place and discover in detail their economic situations over time.

Tax lists are especially welcome as a replacement for records in “burned counties” and areas that have suffered census losses. And even when census records are complete, you often can use tax records to fill the decade between enumerations, especially for rural ancestors who may not appear in annual city directories.

While the current version of the federal income tax (as well as state income levies, most of them introduced during the second half of the 20th century) is off-limits due to privacy, you’ll see that’s generally not the case with such taxes historically. Even the first federal income tax, used to pay for the Civil War in the 1860s, is publicly available.

Here’s how you can make tax records pay off for your genealogy research.

Types of Tax Records

Colonial taxation

One of the most widespread taxes in Colonial times was a flat assessment for each adult male in a household. This was variously called a poll, tithable or head tax. The age at which one was considered a taxable adult varied with the jurisdiction, and older men often could “age out” of the tax, usually between 50 and 60. Exceptions were made in some areas for veterans, ministers and those deemed “paupers” (that is, too poor to pay the tax).

Another typical early tax was on the value of land, because real estate (“real property”) was the source of most wealth. This tax, importantly, was sometimes levied not on the actual owner of the real property but upon the person who was using it. For example, a farmer renting a piece of land would be responsible for paying the tax because he, as the tenant, was reaping the profits from the use of that land.

Certain classes of personal property also were valued and subjected to taxes. The types of property differed by area but included farm animals and carriages, as well as (before 1865) enslaved persons. On some tax returns, landless men whose personal property was of high-enough value to owe tax are identified on separate lists of “inmates,” which in this contexts means tenants or renters and doesn’t signify trouble with the law (and not someone in legal trouble or incarcerated).

In parts of Colonial America, levies called quitrents were a remnant of feudal times when individuals owed taxes or service to their lords. The Mid-Atlantic and Southern colonies often had this sort of annual tax on landowners that went to the proprietor or the English Crown, depending on the area. (Quitrent ended in most places with American independence.)

Town founders also might place quitrents upon town lots as a sort of early form of homeowners’ association fee to fund common projects. As these areas incorporated as governments, those quitrents morphed into taxes.

Colonial-era tax lists often are entirely handwritten. They’re usually arranged in a columnar format, but sometimes the headings for those columns are obscure. Check the first page of the list for headings that may describe what’s listed in the columns. (You’ll see forms with preprinted headings starting generally in the 19th century.)

19th-century taxes

As the nation acquired a degree of financial sophistication in the mid-19th century, some states expanded the reach of their personal property taxes to include the value of investments such as stocks, bonds and money lent out at interest. In some cases, these levies would exempt, for example, values in corporations or banks headquartered within the taxpayer’s home state.

Until the 20th century, the federal government created few tax reports that had genealogically useful information. In its early days, the United States generated most of its revenues with tariffs on imported goods. Any “direct taxes” levied by the federal government were found unlawful by the Supreme Court in 1895. (Note to any would-be tax protesters out there: The 16th Amendment in 1913 superseded this decision.) We’ll discuss the few distinct periods of time during which taxes with individual data were levied later.

For an excellent guide to the history behind taxes in the United States, check out The Genealogist’s Guide to Researching Tax Records by Carol Cook Darrow and Susan Winchester (Heritage Books). The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy, edited by Loretto Dennis Szucs and Sandra Hargreaves Luebking (Ancestry Publishing), has a short section on US taxes, nestled in the chapter on land records.

Sample records

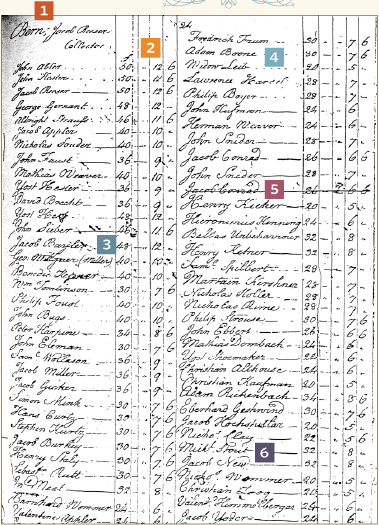

1754 tax list, Pennsylvania

- The beginning of this list for Bern Township, Berks County, Pa., shows name of the township and the name of the tax collector.

- This list values the individual’s land (in Pennsylvania pounds) and shows the tax (with columns for pounds, shillings and pence).

- One occupation (miller) is noted, while the others in this rural township are likely farmers.

- Among taxpayers is the Widow Leib. This is rare, given women’s limited ability to own property; Mrs. Leib was likely the beneficiary of a life estate from her late husband.

- The name crossed out, Jacob Conrad, is a clue that he has moved or died.

- The list isn’t alphabetized, so individuals next to each other are also likely to be next-door neighbors.

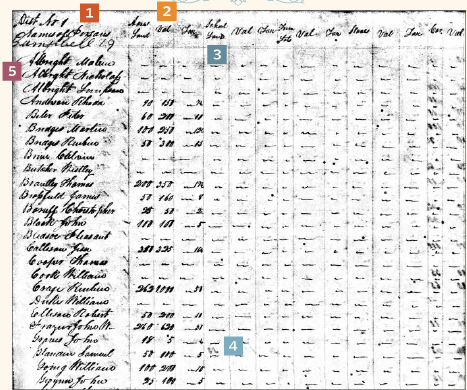

1839 tax list, Tennessee

- The top of the page identifies the place as “District 1” of Campbell County, Tenn.

- The first three columns after the taxpayer’s name list acres, value and tax on land.

- Subsequent columns listed “school land” (set aside for future schools but leased out for farming), lots, slaves, “Car.” (carriages). For each, the sheet has a column for value and tax amount. There are also columns for “white polls” and total state tax.

- When extracting information watch for bleedthrough from marks on the other side of the page.

- This tax list is alphabetized, so we can’t glean clues about neighbors.

Finding Tax Lists

While the specifics vary from state to state (and even from one county or local unit to another), what follows are some rules of thumb for getting the most information from various levels of government.

- Local (cities, boroughs, towns and townships): Most New England states keep their tax records by the town unit. In other states that had townships, the lists may be labeled with those municipal names but most likely were kept on the county level. Records retention (as well as microfilming and digitization) of these local tax lists is generally the lowest of any government level.

- County: Almost all these records—be they head taxes, real or personal property levies—were originally in the custody of a county courthouse office. Some are still there, in their dusty ledger books. Others have been transferred to a countywide archive, a state repository, or a county historical or genealogical society.

- State: Before the 20th century, most states collected taxes similar in form to those on the county level and utilized the county structures for collection of statewide taxes. In many cases, one tax collector gathered the head and property taxes and split them between the levels of government. See Red Book: American State, County, and Town Sources for a summary of tax records for each US state, and consult the Council of State Archivists’ directory.

- Federal: Although federal taxes on individuals were on-again, off-again before the income tax began in 1913, surviving records of them can be fascinating. These pre-1913 taxes were levied to fund war efforts, first in the 1798 “Window Tax” or “Glass Tax” (so named because home valuations were based, in part, on the number of windows) that funded in anticipation of the Quasi-War with France. This tax created a listing of properties (acreages, construction material of homes and barns, structure sizes, etc.) that is unmatched for detail in this time period. A similar direct tax was levied in the 1810s to fund the War of 1812, but states had the option to pay their residents’ share of the tax without assessing them (and, thus without creating records). The Civil War led to another direct tax in 1861 on Union-held lands (including rebellious Confederate states as they came under Union control) as well as the nation’s first income tax in 1862. Read Federal Taxation in America: A History by W. Elliot Brownlee (Cambridge University Press) for more.

Probably the most fertile sources of historical tax lists are state archives. In many cases, these archives also have become the custodians of whatever county or local tax lists have been retained. It’s essential, however, to also check with lower governmental levels; in some areas they may be the only source of extant tax lists.

Be aware that, in some cases, the local or county jurisdictions were responsible for collecting state taxes. That means that you can look for “origination” copies of tax lists on the lower level and “destination” lists on the state level.

Ancestry.com has more than 90 collections dealing with US taxes, housed in its “Court, Land, Wills & Financial” category. Many were created in partnership with state archives around the country and with NARA, the custodian of federal records. Another NARA collection compiles income tax records from the Civil War era, available through the free website FamilySearch.

FamilySearch also has digitized tax records for individual states, but its traditional microfilming practices have placed tax records at a lower priority than other record sets that tend to have more genealogical value (such as vital records). Many of the tax records FamilySearch has sought to microfilm are those needed to substitute for missing or destroyed federal census records, according to David Dilts, a senior research specialist at the FamilySearch Library (FSL) in Salt Lake City.

Search the FamilySearch Catalog by county or town with Online selected under Availability, then look for a taxation heading. (Though all of the FSL’s microfilm has now been scanned, not all has yet been indexed. And some collections are viewable only at the FSL or at certain in-person locations.)

The FHL’s book collection (both at the library and digitized) contains thousands of abstracted and indexed tax lists from across the country. Some books labeled “censuses” may actually be tax lists used to create census substitutes. Check WorldCat for copies of those titles near you, or that can be lent to a local library.

Many state-level collections are the products of local compilers. They may also be available in historical and genealogical libraries in counties where you’re researching.

Note: Many tax lists are created by assessors, leading to spelling variations in your ancestors’ names from year to year. Think phonetically as you search them.

Interpreting Tax Lists

Details in tax records

First and foremost, tax lists tie your ancestor to a particular place, either where he actually lived or sometimes where he owned or used property.

And those mentioned will overwhelmingly be men—the populations included in tax records reflect the laws and mores of the time they were created. Women, for example, are not often found on historical tax lists because of their unequal status under the law. The only exceptions might be widows, who may have been granted income after their husbands died. People of color, too, will be underrepresented.

But the information about those who are listed can be valuable in researching not just the taxpayer, but his whole household. The data in some lists also show the person’s occupation, descriptions of real estate being taxed, descriptions of certain forms of personal property (including farm animals), the number of taxable males in the household, the number of schoolchildren and the number of enslaved people.

Even the simplest lists can be useful because they often differentiate between men of the same name by adding extra information. The tax collector or assessor would use these details to make sure he could determine which man owed what tax. Examples of this added data might be first names of the fathers for each of two same-named men, the men’s occupations (even when not required by the form), or some geographic locator such as “by the Bow Creek.”

Contextual information from tax lists can also be useful. For example, people listed above or below your ancestor in a non-alphabetized tax list might well have been his neighbors; collectors and assessors generally rode a circuit through the community. And any crossed-out names would indicate someone either died or moved since the last assessment.

Tip: Like other secondary sources, published tax lists may “edit out” some details in the original lists, and they are subject to copying errors. Once you find your relative in a compilation, use the details to look for the original tax record.

In some states, agents made special notes about school-aged children. This may have been a simple tally of the numbers of schoolchildren in each household. Or, as in Pennsylvania, the names of families who could not pay fees for public education (before the advent of the government-funded schools) were sometimes listed at the end of tax registers.

Tracking your ancestor’s land

When seeking out tax lists, consider your ancestor’s time and place like a cross-hairs. That will help you find the correct tax list and interpret its data correctly.

For example, don’t assume that an ancestor’s land is in the same county now that it was in 1850. County borders may have shifted, or new counties might have been formed out of old. As a result, land and tax records may be in different counties. Likewise, as cities grew, they annexed land from neighboring townships or unincorporated areas of counties, so an area that’s in a city today might well have been part of a distinct county when your ancestor lived there.

In public-land states, real estate taxes were usually organized by township and range, with the section coordinates given right in the tax register. That makes it easier to identify the land on a modern map. In state-land states, on the other hand, landowners’ holdings are usually identified only by a number of acres, which might only roughly correspond with reality. Those acreages, however, usually stay consistent unless a change in use or owner happened, so they’re good markers for shifts in ancestors’ status.

The history of tax law

Research the laws behind tax lists to better understand what information they sought to collect and where records might be today. You may find a citation of the relevant law at the beginning of a set of tax records, but you might have to search contemporary state statutes for further information. The book Genealogy and the Law by Kay Haviland Freilich and William Freilich (National Genealogical Society) is a good starting point, as is Judy Russell’s “Legal Genealogist” blog.

The age when men’s names appeared on some type of tax list was determined by law—16, 18 and 21 were popular options—and usually meant they had to pay the head tax even if these “single freemen” (as they were called in some jurisdictions) didn’t own land or significant personal property.

It’s not unusual for men to have fibbed about their age, and thus be listed two or three years later than their ages would justify. (Attracting the tax collector’s eye was no more popular in bygone days than today!) Using these portions of the lists can help you trace family units that lack children’s birth records by studying when the males are first taxed.

Eventually, many men went on to pay taxes on personal property, either by purchasing land or gaining dowry from their fathers-in-law. In this way, you can trace ancestors from adulthood into old age: from paying a simple head tax upon coming of age, to paying a levy on personal property, to dying or aging out of tax liability altogether. Tax lists also indicate migrations or other moves from one area to another.

Alternatives to Tax Records

Various levels of government have collected any number of other taxes that aren’t found in a list format. For instance, states have enacted inheritance or estate taxes that will list names of heirs (most often relatives of the deceased). Because these are state-level records, you sometimes can use them as substitutes for the probate records of “burned counties.” In those cases, original copies at the courthouse will likely have perished. But copies of the inheritance or estate tax data sent to a higher government office may still exist.

Records of business licenses, liquor and cigarette taxes are likely to have limited personal information (except for the individual licensee). Same for the previously mentioned school taxes, though those in a few states (Pennsylvania and Georgia, for example) include notes about school-aged children. In Pennsylvania, the names of families who could not pay fees for public education (before the advent of the free basic schools) were listed at the end of the tax registers. Georgia’s ledgers listed the numbers of schoolchildren in each household.

If you’re striking out with tax lists and related records, look for land and probate records for clues about your ancestor’s income and place of residence. Wills, in particular, often detail personal assets like land and personal property.

Fast Facts about Tax Records

- Coverage: Varies by location, with earliest in Colonial times. Regular federal tax records begin in the 20th century, but are largely restricted by privacy laws

- Jurisdiction where kept: Created variously by the town/city, county, state and federal governments, then held at that jurisdiction level. State archives may have copies of city or county records.

- Primary source details: Names of individual taxpayers; description of land or personal property being taxed

- Secondary source details: Neighbors’ names and property; shifts in ownership of property; estimated birth dates of single men; death of ancestor; whether an ancestor moved

- Search terms: Name of the government unit issuing the tax (such as Pennsylvania state) plus tax lists or tax records or taxation

- How to find in the FamilySearch Catalog: Run a Places search for the names of the state, county and/or town of interest, then look for the Taxation category. If you search for just the state, you may miss some potentially helpful entries.

- Alternate and substitute records: City and county directories; federal and state censuses; probate records; land records

Toolkit

Websites, online articles, and digitized books

- Cyndi’s List: Taxes

- “Ending the Poll Tax” by Judy G. Russell

- “The Good News About Taxes: Finding and Using Tax Records in Your Genealogical Research” by Susan Jackman at Archives.com

- “Income Tax Records of the Civil War Years” by Cynthia G. Fox at the National Archives

- “Known, Extant 1798 Direct Tax Lists” by Prologue magazine

- The Quit-Rent System in the American Colonies by Beverly Waugh Bond and digitized at the Internet Archive

- Red Book: American State, County and Town Sources edited by Alice Eichholz and digitized at RootsWeb

- Tax History Museum: Tax History Project

Publications and resources

- The Beginner’s Guide to Using Tax Lists by Cornelius Carroll (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Courthouse Research for Family Historians by Christine Rose (CR Publications)

- Federal Taxation in America by W. Elliot Brownlee (Woodrow Wilson Center Press)

- The Genealogist’s Guide to Researching Tax Records by Carol Cooke Darrow and Susan Winchester (Heritage Books)

- Genealogy and the Law: A Guide to Legal Sources for the Family Historian by Kay Haviland Freilich and William B. Freilich (National Genealogical Society)

- Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790-1920 by William Thorndale and William Dollarhide (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy, 3rd edition, edited by Loretto Dennis Szucs and Sandra Hargreaves Luebking (Ancestry Publishing)

- Tax Records: A Common Source with an Uncommon Value by Arlene H. Eakle (Genealogical Institute)

Organizations and archives

Exercises

Quiz

- In the records of what government levels might you find tax records for your ancestor?

- Which of the following is the tax LEAST likely to reveal genealogically useful information about your ancestor

- a. poll taxes

- b. personal property taxes

- c. income taxes

- d. cigarette taxes

- The general trend in taxation by local, county and state units was from:

- a. income to tariffs

- b. wealth to income

- c. tariffs to real property

- d. real property to personal property

Answers

1. Local, county, state and federal 2. d (unless your ancestor sold cigarettes!) 3. b Exercise A 1. White F. Griswold and Moses Hallett 2. Both in Denver 3. Dentist and lawyer; each owed $10 4.

Exercise A: Look for tax lists

Go to FamilySearch’s database of US Internal Revenue Assessment Lists (1862–1874), and look for Colorado, Arapahoe County from 1862 to 1863. Find image 14.

- What are the names of the top two listed individuals?

- Where did they reside?

- What were their occupations and how much tax did they owe for licenses?

- Write a citation for this record.

United States Internal Revenue Assessment Lists, 1862-1874, images online, FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1942-32469-14703-28?cc=2075263&wc=SD5P-JHZ:387486101,387608501,387486103 : accessed 10 January 2015).

Exercise B: Extract information from a tax record

Pick an ancestor whose tax records you want to find using an online database of your choice. Use the worksheet and extraction form in the back of this workbook to record your results.

Related Reads

Versions of this article appeared in the May/June 2015 and July/August 2022 issues of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: April 2025