It’s a discovery genealogists hate to make: An ancestor lived in a “burned county.” Originally the term for counties in which courthouse fires destroyed records, the phrase now also applies to courthouses that have lost records due to other disasters, such as floods, explosions, theft, riots, tornadoes, Indian attacks and officials’ misguided cleaning frenzies.

What are your chances of coming across a burned county in your research? Pretty good. Courthouse disasters were common in the days before modern building codes. By one reckoning, the term applies to about 20 percent of Ohio counties (one in five!). It’s worse in the South, in part due to the Civil War. More than 40 percent of counties in Georgia and Alabama, and nearly as many in Mississippi, have suffered courthouse damage at least once.

Not all of these disasters destroyed every record, and that’s part of the researcher’s challenge. Clerks’ tales of total destruction may be a smokescreen: Surviving and alternate records may exist in the courthouse or elsewhere. It can be a painstaking process, but it’s often possible to rebuild your relatives’ records from the ashes of courthouse disasters. You have to be organized, determined and thorough, and follow these five steps.

1. Assess the damage.

Determine the date of the courthouse calamity, or dates if there were multiple events. Consult more than one source and give preference to sources that cite original reports of the disaster (such as newspaper coverage). Look in local histories and genealogical guides, at courthouse or genealogical society websites, and in the Burned Counties page of the FamilySearch wiki. The date is crucial, because records dating after that time should be unaffected. Note the date on a Burned County Records Inventory form.

Next, it’s time to find out exactly which records perished and which ones didn’t. Sometimes a fire or flood affected only part of a building or only some records. Sometimes the records you want were stored elsewhere and therefore unaffected by flames or floodwater. Here’s an eye-opening example: Indiana has about 25 burned counties, but in most counties some records survived, and in eight counties, all genealogically relevant records were saved.

Confirm the extent of record destruction by speaking with local experts: historians, archivists, professional researchers and longtime genealogists. Push (politely) for detailed descriptions of records lost, as well as those that were salvaged and restored. If you’re told that deeds were affected, ask which years. Ask about related records: indexes, separate mortgage books, geographic abstracts, etc. Record your answers on your inventory form.

2. Look for inventories.

Lists of records that once existed will help you find substitutes for what’s missing. If a record was around in 1940, for example, and no calamities have occurred since then, you know it probably still exists. Many counties and states have inventories records since the disaster-prone 1800s. There’s no guarantee that the records are still in the same location as when the inventory was taken, or even still exist, but at least you have a starting point.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) conducted the most famous and widespread inventories during the late 1930s and early 1940s. These Historical Record Surveys document a variety of records. Some even discovered lost collections: WPA workers in Dubois, Ind., found 10 boxes of deeds that survived an 1839 courthouse fire. The surveys differed in each state. Missouri’s includes county government, church and vital records, manuscripts, and federal archives collections. In Texas, they skipped church records and some western counties altogether, but processed more than 10 million documents and transcribed or indexed thousands of property, vital, court and estate records.

Look first for Historical Records Surveys in state libraries, archives or historical societies. Copies of some may have ended up on the county level. A fast (but not guaranteed) search method is to enter “Historical Record Survey” and the state name in your web browser: information for both Missouri and Texas come up in Google with this method.

If records listed in inventories are no longer at the location given, look for them elsewhere, such as a state or regional archive. Check with these institutions and their county counterparts. At each place, ask an expert, “Where else should I look for this record?” Then look for microfilmed records in the FamilySearch catalog; click Search, then Catalog, and search by county. Check with local genealogical and historical societies, too. Be thorough and note your findings on the Inventory form.

3. Build on existing foundations.

As you sift through proverbial record ruins, use what you discover for all it’s worth. Remaining records can provide a foundation upon which to reconstruct your ancestor’s life. Scour them for every clue they hold. Document and follow up on those clues. And don’t neglect less-common surviving sources that you may overlook when the records-pickings are ripe.

Records that survived a fire or flood may have water or smoke damage, but may still be usable. It’s worth asking, if you hope to handle them personally, what condition they’re in and whether you should dress for messy work. Be respectful of limited access policies; you may need to wait or pay for a staff member’s help. Ask whether microfilmed or other copies exist. A photocopied or scanned original is more reliable than a typed abstract or index, though the latter may be all that’s available.

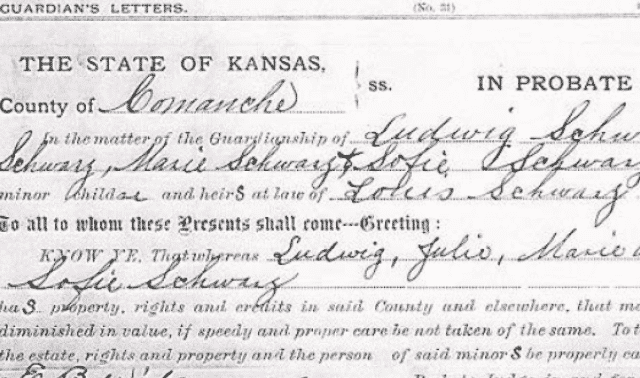

It can take a practiced eye to recognize every valuable clue you find in county government documents. Make copies of originals for later reference. Then abstract or transcribe the unique data. For long legal documents that mostly consist of standard language, abstract (or extract) everything unique about it, including names, dates, dollar amounts, any legal action or claim taking place, etc. If you’re not sure whether you’re reading something unique or boilerplate, compare the document to similar ones in the same record set. You’ll quickly determine what makes yours unique.

You may want to fully transcribe documents that are difficult to read or are rich in unique information, such as deeds or divorce proceedings. This way you can better digest the meaning and capture clues buried in the narrative. Review the evidence you find to see if it leads to other clues. For example, if you find family listed in poorhouse records, look for a financial trail leading that direction: tax records, court-ordered support, a foreclosure or bankruptcy filing, etc.

Finally, don’t discount record types you haven’t used before. County offices have kept all kinds of interesting paperwork in the past, from public school attendance lists to coroner’s records. Perhaps military discharge transcripts or poorhouse records survived a blaze. You may not think anyone in your family would be listed, but try. Use our free Research Trackers to organize your findings.

4. Reconstruct records.

It’s true that county sources are often at the heart of family history research. But don’t get tunnel vision. Look for records other government offices and community sources kept. See whether someone has already made efforts to recreate the record. In a pinch, these may provide the dates, places or other information you’re looking for, or they may at least point to it.

First, look for delayed and re-recorded records in the burned county. Officials sometimes asked the locals to submit information about their marriages, land purchases and other events that were recorded at the courthouse before the disaster. Property records were usually re-recorded because of their financial importance. Look for re-recorded deeds soon after the disaster or with the next transaction for that property. Other records may have been re-recorded, too, sometimes long after the fact. Your adult relative may have applied for a delayed birth record if an original was lost or never existed. This was common in the 1930s, when people started needing proof of birth to apply for Social Security benefits.

Next, look to other government sources. States may have copies of vital records, especially for 20th-century births and deaths. Many states have taken censuses. You can search some of these on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch; also consult our US State Guides or State Census Records by Ann S. Lainhart (Genealogical Publishing Co.) to learn more. Federal censuses (searchable on most genealogy data sites) and military paperwork can take you a long way, too.

Last but definitely not least, look to non-government sources created in or about your ancestor’s community: newspapers, church records, city directories, local and county histories, maps and atlases, and data compilations that government, historical or genealogical organizations created as substitutes for lost ones. See the Lost and Found chart below for quick ideas on where to look for certain types of information.

5. Meet the neighbors.

If you’re facing a really tough reconstruction case, you may need to turn to the records of your relative’s family and friends. To use a new metaphor: In the days before interstate highways, the only route from one small town to the next was probably an indirect one with many roads. If county records are like genealogical superhighways, in their absence you may need to take a long and winding trail through other people’s backyards … er, records.

Turn your research focus to your ancestor’s family members and close associates. Let’s say you’re looking for Rose Krankota O’Hotnicky’s parents. You find her living as a newlywed in the 1910 census, where you also find Jon and Anna Krankota across the street. They list four living children but only three are in their household. Is Rose the fourth? Her county birth and marriage records have been lost. So you search for those three children and find a delayed birth record for one son. Listed as a witness? Rose Krankota O’Hotnicky—identified as his sister.

This research strategy can seem overwhelming. It’ll become easier if you make it a habit to watch for relatives and associates while searching for your ancestor the first time around. Keep tabs on each person in family group sheets or your family tree database. Note the sources of each specific piece of information for each person. You won’t have to enter the full source information more than once if you create a source record in your family tree software or use reference software such as Evernote or Zotero.

Tip: Did your ancestral county boundaries change while your family lived there? If so, their records may be at the county seat of the parent county—which, if you’re lucky, didn’t suffer a courthouse fire.

Tip: Local genealogical societies and libraries are great sources of information about record losses and how to get around them. Connect with these organizations online through their websites.

Be persistent

Record loss doesn’t have to mean relative loss if you’re persistent, thorough and a careful record-keeper. You may not recover every lost detail about a person’s life from the proverbial ashes of county records. But what you do discover may be cause a family phoenix to rise from those ashes: a long-lost relative, hazy through the smoke, yet real and beautiful, and worth every research effort.

Not every loss happened at a county courthouse. Learn more about two losses of federal records—the 1890 census and 20th-century military records.

Lost and Found: Look for Other Sources

If old records important to your genealogical research have been lost, look to other sources for the information you want. Remember that the reliability of the alternate resource depends how long after the event the record was created, and by whom. For example, if your ancestors’ marriage license was burned, a church marriage record created at the time they wed is a reliable source for their marriage date and place. A tombstone inscription giving a marriage date is less reliable.

| Looking for information on … | Best alternate records | Other possibilities |

| birth | church, delayed birth, family Bible | cemetery, census, death, draft registration, military enlistment, naturalization, pension, obituary, Social Security application (SS-5), tombstone |

| marriage | church, divorce, family Bible, newspaper announcements | census, naturalization, pension, obituary, probate, SS-5 (for maiden name), tombstone inscription |

| death | church, cemetery, family Bible, obituary, probate, tombstone | cemetery, directories, military, pension, taxes |

| property ownership | re-recorded deeds, including those of adjacent, prior or subsequent landowners | geographic abstracts, historical atlases, plat maps, taxes |

A version of this article appeared in the October/November 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: December 2024

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in an affiliate program through Genealogical Publishing Co. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.