Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Are you new to courthouse genealogy? In this article, you’ll get the chance to follow along on the adventures of a courthouse genealogy research newbie and learn a few tricks that you can apply to your own research.

The Beginning of the Adventure

OK, I confess: I was a Courthouse Virgin. Except to get a marriage license and register our wills and automobiles, I had only a passing acquaintance with the great American institution known as the county courthouse. I’d certainly never visited a courthouse on a genealogical mission.

The reason’s simple: I’d never had to. The records I’ve needed so far in my research have been available on the Internet, in libraries or on microfilm from my local Family History Center. Much of my research has been on ancestral places far from my own home, anyway, so showing up at my ancestral courthouse wasn’t a practical option. I’d been able to write away for various birth, death and marriage certificates from my father’s Illinois hometown, for example.

ADVERTISEMENT

Still, I knew the day would come when the only way around one of those blasted genealogical “brick walls” would be through a courthouse door. Some records just can’t be obtained any other way. I also knew that exploring in person — where you can make connections, follow up on leads and generally play genealogy detective — can solve puzzles that resist other approaches.

Before I committed my time, money and energy to digging into the courthouses in Rock Island, Ill., or Opelika, Ala., however, I wanted some practice — closer to home and with lower stakes than my own ancestry. I decided I’d use other people’s ancestors as my guinea pigs, and get my courthouse initiation right here in my own county. So I’d remember what I learned, I recorded the whole experience in my handy research journal.

The First Courthouse Visit

Nov. 19, 11 a.m.

The wisdom of this plan is quickly confirmed as soon as I start preparing for my inaugural courthouse visit. For one thing, many of the records I’d naively assumed would be awaiting me down at the courthouse simply aren’t there. If I’d traveled halfway across the country to Opelika, Ala., to find a birth certificate, only to learn the piece of paper I wanted actually was in the Alabama state capital, Montgomery — or, worse, that it had perished in one of those all-too-common courthouse fires — I’d be miffed, to put it mildly. Better to learn with my little backyard experiment and not risk nonrefundable airline tickets.

ADVERTISEMENT

I begin preparations by consulting a genealogy reference book. I used Ancestry’s Red Book, which you can find at many libraries. If an exceptionally helpful volunteer oversees your target county’s USGenWeb site, you might even find the basics online.

The information you’re after is the records the county holds — what type and how far back they go. You can’t just assume that the county courthouse has every official document ever created therein. Besides getting barbecued in fires, older records often are moved to state archives and historical societies. And as America grew westward, existing counties spawned new ones, meaning the records you seek may be in the courthouse of the “parent” county. Ask yourself: What county was it back then? Grant County, NM, where I live, was part of Doña Ana County until 1868. In turn, Grant County helped give birth to Luna County in 1901 and Hidalgo County in 1919.

According to the Red Book, Grant County has marriage records from 1868 on, land records beginning in 1872 and probate records dating from 1887. But where the heck are the birth and death records? It turns out these are kept by the state health department in Santa Fe, and only immediate relatives or others demonstrating a “tangible legal interest” can view birth records newer than 100 years old or death records from the past 50 years.

Wait, Where are They?

Nov. 22, 2 p.m.

At least now I know what I might be able to look for. Excited to make my first foray into courthouse genealogy, I imagine myself striding up the steps of the handsome old courthouse on Cooper Street, pen and pad in hand, ready to dive in.

But something niggles at my brain. Is that where the county records really are? When we recently went to file our wills, we met our attorney at the county clerk’s office — inside the Grant County Administration Building, a modern, nondescript office building off the highway. Could it be … ?

I let my fingers do the walking before I walk into the wrong building. Sure enough, all the old records have been moved to the county administration building. Unless I’m planning to do jury duty, I can stay out of the old courthouse. (If you need to call a faraway courthouse, get contact information from USGenWeb or the National Association of Counties website.)

Nov. 24, 10:30 a.m.

I’m really all set now. I’ve even found some other people’s ancestors to research. Originally I thought of looking for documents about Billy the Kid, aka William Bonney, aka Henry McCarty, who spent his formative years here in Silver City, NM. But the absence of birth and death records spoiled that notion: If there’s a death record for his mother, Catherine Antrim, who died here Sept. 16, 1874, it’s in Santa Fe. And her will, if she had one, would’ve been probated before probate records start here in 1887.

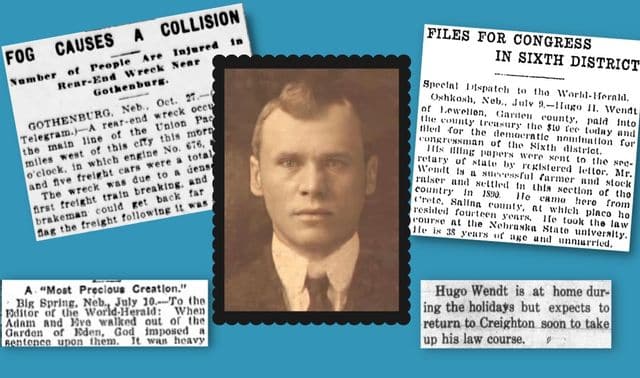

So instead I use online databases to find families with local connections. What I wind up with is pretty similar to what any beginning genealogist might know about an ancestor before doing courthouse research: some possible names and dates, all needing proof.

The Friday after Thanksgiving, I figure, would be perfect for my baptism by fire. I can take the day off and learn the ins and outs of courthouse research at my leisure. It should be quiet, with most people out hunting for bargains instead of ancestors.

One thing, though: Will the courthouse — the county administration building, rather — be open that day? Another phone call saves me another wasted trip. Nope, the county clerk’s office will be closed.

Don’t assume your courthouse will be open, even if it’s not an obvious holiday. The building might be under renovation. Or the county could celebrate a day you don’t, such as Robert E. Lee’s birthday (Jan. 19), which many Southern states still observe. Call ahead, and also check the county’s website, if it has one. (And while you’re at it, you might want to ask about parking options.)

Through the Doors

Dec. 1, 10 a.m.

The post-Thanksgiving shopping frenzy behind me, I, at last, make my pilgrimage to the county clerk’s office — a cheery, computer-dotted corner of the administration complex. I explain that I want to do genealogical research, and the friendly woman at the front desk leads the way to a side room with a few long tables and an array of tightly packed shelves. She shows me how to work the black hand crank that slides apart the hydraulically assisted shelves for access, then leaves me on my own to explore.

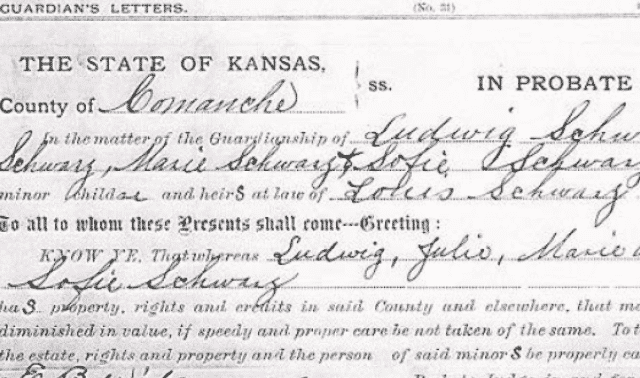

I start with the will books, hauling down a tall, leather-bound volume with “1878 to 1918” handwritten in black ink on the spine. I must confess, I expect I’ll simply be able to turn to the page corresponding to the date of death for my subject and find the will I want. Reality soon obliterates that genealogical fantasy: Although the wills proceed more or less chronologically, they’re not arranged quite so neatly. The likely death date I have, after all, isn’t the same as the date the will would’ve been written, filed or probated. So I have to flip through page after page, scanning the names that some helpful person wrote in the margins. These oldest wills were transcribed by hand, so it’s slow going.

Even though I’ve picked several candidates to search for, I strike out again and again. Evidently, many early residents of the New Mexico Territory and our fledgling state died without the nicety of leaving a will. (Billy the Kid’s victims, for example, presumably didn’t get the chance.) Or maybe the will never made it into the official books. Or could be I’m simply overlooking something.

Dec. 1, 10:30 a.m.

Finally, I hit pay dirt, though not quite how I’d expected. I find the will of Thomas J. Clark Sr., the father of one of my targets. Sure enough, it mentions son Arthur L. Clark, one of eight children with wife Mary. Thomas’ will was written June 18, 1912, filed Dec. 9, 1919, and probated March 1, 1920 — so he died sometime in late 1919 or early 1920. I learn Arthur’s father was a rancher who also owned the Gila Hotel & Store. I’m tempted to keep reading. Old wills, it turns out, provide an unusual glimpse into daily life way back when.

But I’m after answers, not local color. Giving up on for now on finding the will of Arthur himself, I move on to marriage records.

Finding Marriage Records in Courthouse Research

Dec. 1, 10:45 a.m.

The book of marriage records covering the years 1872 to 1899 is a battered leather-bound register, held together at the seams with thick strips of clear tape. I worry about damaging it further as I muscle it off its shelf, but no clerk comes screaming, “Be careful!”

I start flipping pages and am confounded once again by the order of things. The entries seem to be in alphabetical order by the groom’s last name — but no, here’s a Corbin before Castillo. What gives? Genealogical success in the courthouse, I’m slowly learning, often depends on figuring out the filing schemes of yesteryear’s county clerks.

On closer inspection, I see the entries are organized by the first letter of the groom’s last name — and then chronologically. Once I’ve made this breakthrough, I quickly find Arthur L. Clark’s marriage to Phoebe Ann Patten at the bottom of the fourth double-page spread of C entries. The joyous event took place Dec. 6, 1895, celebrated by Isaac Givens, justice of the peace, and witnessed by Thomas J. Clark Jr. (the groom’s brother, I know from their father’s will) and Pearl Childers.

Dec. 1, 11:05 a.m.

While I’m in the stacks of marriage records, I look up the next family on my list. Since I’ve figured out the system, it’s a snap to find William D. Murray’s April 26, 1893, marriage to Martha Orr. But the 19th-century handwriting stumps me on the minister’s name (Rev. Aug. Mann?). The witnesses are Charles B. Rosecrans and Josephine Murray, as best I can tell.

Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way

Dec. 1, 11:15 a.m.

Back to the will books — this time, the 1918 to 1956 volume, bound in what looks like white-washed cardboard — to find William D. Murray’s will. The transcriptions are typed now, but the timesaving marginal notes are absent.

I have to scan each page more closely, which means that purely by chance I find a “W.D. Murray” as a witness to the Aug. 3, 1944, will of an Anna M. Phelps. There he is again, witnessing for Margaret M. Tuphan on April 25, 1951. So far, so good in support of my pedigree-chart death date of May 5, 1952 — at least he’s still alive the year before.

Dec. 1, 11:30 a.m.

But William D. Murray’s will refuses to reveal itself. I’m starting to get bleary-eyed and hungry (it’s almost lunchtime).

Finally, I encounter another of those happy accidents that I’m coming to realize are essential to courthouse success. Several pages past where William’s will ought to have been, I stumble across the will for Martha Murray, his widow. I know he’s indeed dead by Martha’s Aug. 31, 1954, filing date, because her will refers to Martha’s “inheritance from my deceased husband W.D. Murray.” The will gives me other clues, too: bequests to daughters Lyda M. Ryan and Hazel M. Barker. She names James M. Ryan — her son-in-law, presumably — as executor.

The will was probated Sept. 28, 1954, and there’s a number, 1913, which I hope will enable me to look up the actual probate file: all the various legal documents necessary to settle an estate.

Dec. 1, 11:43 a.m.

Alas, the shelves of probate files — each folder with a tab bearing its number and the deceased’s name — begin with number 2003. My Martha Murray probate is too early.

Good Observations

Dec. 1, 11:50 a.m.

I’ve shrugged back into my coat, grabbed my pedigree charts and notebook, and am heading for the door when I notice the boxlike metal files arranged against the wall. I hadn’t really seen them before. The drawers have various labels, but I’m immediately drawn to the ones for marriage applications.

These turn out to be filed by year, and by some inscrutable numbering system within each year. I didn’t recall any matching file numbers from the book of marriage records, so I start paging through 1893 by hand for the Murray-Orr nuptials. About a quarter of the way through, at number 593, I find it: their actual marriage application. I don’t learn anything new here except that they had a Roman Catholic ceremony.

Dec. 1, 11:57 a.m.

Intrigued now, I take off my coat and begin scanning labels on the metal drawers: coroner’s files, deeds, mining claims, incorporation inquest files, deeds, mining claims, incorporation papers, county commission notes. Booklets containing indexes to the town’s cemeteries are shoved sideways into another drawer.

Most drawers are labeled with a large letter of the alphabet, several drawers per letter, but it’s not immediately clear what’s alphabetized within. Incorporation papers? Seems like a lot for a small town. Looking more closely, I see each label also has a range of numbers, like those on the probate files. In the uppermost left corner, on the first A label, is penciled the small words “Probate Files.” Here are the files before number 2003!

Mixed-Up Files

Dec. 1, 12:05 p.m.

Really longing for lunch, but very curious, I open the first drawer I see with a range that to contain Martha Murray’s probate would seem to contain Martha Murray’s probate file number 1913. But the dusty white files within, each tied with string, are too fat and thus too few to represent the whole range on the label. There’s no number 1913.

I look again and realize: another mixed-up filing scheme. Unlike the shelved files that begin with number 2003 and run numerically, these are organized alphabetically (hence the big letters — duh) and then by file number.

Moving over to the M drawers, I find one with the right range of numbers. And here’s Martha Murray at number 1913.

Dec. 1, 12:12 p.m.

A wild idea hits me. Even though I couldn’t find William D. Murray’s will in the books, maybe it’s here. If he died only a few years before, his file should be just a couple drawers to the left.

What do you know? Number 1779, filed right next door, holds all the paperwork relating to the last will and testament of William D. Murray.

What have I learned, now that I’m no longer a Courthouse Virgin? Be prepared. Do your homework before you go. For one thing, to make sure you’re going to the right place. Expect some tedious searching, not instant answers. Try to figure out the filing scheme(s). Take advantage of serendipity — accidental discoveries that aren’t quite what you set out to find, but that can lead you to answers nonetheless. Above all, think like a detective: The courthouse is filled with clues, but it’s up to you to ferret them out and learn what they mean. Oh, and remember to eat a big breakfast — you might miss lunch.

Prepare for Trial

Most courthouses have rules for what you can take inside. Some don’t allow pens, tote bags or food, and others couldn’t care less, so call ahead to ask about restrictions. Put these items on your packing list:

- prioritized list of records to look for

- pedigree charts and family group sheets for people you’re researching

- change for photocopiers and parking meters

- pens and/or mechanical pencils

- notepads

- laptop computer (inquire about hookups)

- digital camera and extra battery

- hand wipes

- dust mask

- magnifying glass

- snack and water bottle

ADVERTISEMENT