Have tough questions about birth records? From restricted access to researching “illegitimate” ancestors to recording births at sea, our genealogy records experts have the answers!

Jump to:

Q: My great-great-grandfather Edwin Lemon was born in Chester County, Penn., in 1818. This is all I can find about him. How do I find his parent’s names and the month and day of his birth?

Q: The 1900 census in Tennessee shows my mother as born in 1895. In 1910, she’s listed as born in 1900. How can I verify which birth date is true? I can’t find a birth record in Tennessee for either year.

Q: How do you trace an “illegitimate” ancestor? My grandfather was born in 1887 and was illegitimate. His biological father was supposedly highly connected.

Q: My mother’s Social Security application lists her birthplace as Trenton, NJ, but the city has no record of her birth. Where else can I look?

Q: I’ve determined the information on my own birth certificate is incorrect. Should I submit the correct information to the state so my descendants aren’t as confused as I was?

Q: My grandmother was born in South Carolina in 1910—before the state began keeping birth records in 1915. But I’m pretty sure she had a passport. Didn’t you need a birth certificate for that?

Q: I’m having difficulties getting a relative’s birth records because I live in a state that restricts vital records. I’m not an immediate family member, and thus not entitled to the record. Any suggestions?

Q: If someone was born aboard an immigrant ship traveling to America, how and where is the birth recorded?

Q: I’m looking for an ancestor born before his hometown began keeping birth records. Would his birth be in the records of the midwife who delivered him?

Q: My great-grandmother Ona May Boyer’s death certificate gives Washington as her birthplace on April 7, 1887. How can I find out where exactly she was born? I’ve documented older siblings born in Iowa and younger ones in Oregon.

Q: I thought a birth certificate, even a delayed one, was required to get a Social Security number (SSN). Yet, when I find SSNs for my deceased family members, I don’t always find birth certificates. Why?

Q: My mother was born in Matanzas, Cuba, in 1914. She passed away in 1986. How can I obtain a copy of her Cuban birth certificate?

Related Reads

Q: My great-great-grandfather Edwin Lemon was born in Chester County, Penn., in 1818. This is all I can find about him. How do I find his parent’s names and the month and day of his birth?

A: When you boil it down, finding parents’ names is what genealogy research is all about. Make sure you’ve taken the basic steps to talk to family, search for home sources, and research your more-recent Lemon ancestors.

You don’t say how you know Lemon’s birthplace is Chester County. Family stories and even later records identifying birthplaces sometimes turn out to be wrong. Look into Chester County history and see if boundary changes could have affected where you should look for records on Edwin.

Assuming Chester County is the right place, you’re not likely to find a vital record from 1818, and unfortunately, no magical record is guaranteed to give you the information you need. Instead, search for records on all the members of the Lemon family and create a timeline of their locations and dates. Eventually the clues will add up to answers. Here are some records to search for:

Baptismal and other religious records

Lutheran, Reformed, Quaker, Moravian and Roman Catholic were common denominations in Pennsylvania. Check the Family History Library (FHL) online catalog for records from churches in Chester County. (Run a place search on the county, then click the church records heading.)

Court records

If you know when Lemon’s father died, look for will and estate records. But your ancestors could have shown up in court records for land purchases, trials and other reasons. The subscription site Ancestry.com has an index to Chester County wills from 1713 to 1825 and a court records index covering the late 1600s to the mid-1700s.

Tax records

Everyone had to pay taxes, so search for Lemons in Chester County tax records when your ancestors lived there.

Newspapers

Since Ben Franklin started the Pennsylvania Gazette, newspapers have been a fixture in the Keystone State. Find out which papers covered Chester County, and where they’re available, at the Chronicling America Web site. Also visit the Pennsylvania Newspaper Project site.

For more ideas, you’ll want to use the Pennsylvania State Archives genealogical research guides. Here, you can see the types of county records available and what the archives has on microfilm for each county. As one of the three original counties William Penn created in 1682, Chester County is the subject of a lot of microfilm.

Answer provided by Allison Dolan

Q: The 1900 census in Tennessee shows my mother as born in 1895. In 1910, she’s listed as born in 1900. How can I verify which birth date is true? I can’t find a birth record in Tennessee for either year.

A: Our ancestors weren’t as meticulous about dates (or spellings) as we might like, so sometimes such information conflicts. Unless you can find evidence such as a birth certificate or baptismal record (and assuming you’ve examined the original records to verify what they say), your best strategy is to rely on what a court might call a “preponderance of evidence.” Look for other records that provide a birth year: a marriage record, cemetery record, Social Security Death Index, obituaries, later censuses, state censuses (unfortunately not applicable in Tennessee), military records and so on. If most of these sources agree, even with a few outliers, you can assume the most common date is correct.

Lacking additional clues as to your mother’s birth date, you can guess that the record generated closest to the event is more likely to be correct. In this case, it’s unlikely an infant would’ve been misdated as a 5-year-old; the 1895 date is probably correct.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

Q: How do you trace an “illegitimate” ancestor? My grandfather was born in 1887 and was illegitimate. His biological father was supposedly highly connected.

A: Ancestral attitudes toward children born to unmarried women varied from shame and scorn to a tacit acknowledgement. Henry VIII of England, for example, acknowledged that he was the father of a bastard son, Henry Fitzroy (though he likely had others). In the 19th century, however, illegitimacy was strongly frowned upon and the children usually could not inherit (although a trust fund might be set up for the child, a source of possible clues). England’s 1834 Poor Law “reform” included a Bastardy Clause that absolved the father of responsibility for his child, purportedly to discourage women from becoming pregnant to elicit financial support.

Nonetheless, “absolutely everyone will have at least one, if not several, illegitimate ancestors,” says Ruth Paley, author of My Ancestor Was a Bastard (Society of Genealogists). Clues include a birth certificate lacking a father’s name, the absence of a marriage record, a note in church records, or simply dates that don’t add up. Long age gaps between siblings are red flags: Biological grandparents passing a baby off as their own was a common cover-up.

Despite the desire for secrecy, naming practices can point to possible paternity. The father’s surname might be given as a middle name, for example. If you have an address for the birth, it might be that of a workhouse or unwed mothers’ home which could have extant records.

In England, illegitimate ancestors born prior to the 1834 reform could actually be easier to track because local parishes had to pay for the children’s care; the church in turn might go after the father for funds, creating a paper trail. This could include “bastardy examinations” to prove paternity.

A version of this article appeared in the October/November 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

Q: My mother’s Social Security application lists her birthplace as Trenton, NJ, but the city has no record of her birth. Where else can I look?

A: When an ancestor doesn’t appear where she’s “supposed to be” in vital records, keep in mind that record-keeping back when wasn’t as persnickety as it is today. Names and their spellings were equally flexible, so of course the first thing you should do is explore variants for your mother’s maiden name. Censuses and city directories can help with this, and they can narrow where your mother’s family lived in the years surrounding her birth.

Although New Jersey vital records are available from local registrars, you also can request them from the state Department of Health and Senior Services. Supply your mother’s full name, date of birth and the city or county where she was born. Because you’ve already struck out with Trenton proper, you might just say Mercer County, where Trenton is located. Birth records begin in 1901 and are available for deceased people born more than 80 years ago.

If that centralized source can’t help you, consider broadening your efforts to local registrars in towns near Trenton. Your mother may have told the Social Security Administration that she was born in Trenton because that’s the biggest city near her actual birthplace. Mercer County has 13 local registrars with vital records.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2012 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

Q: I’ve determined the information on my own birth certificate is incorrect. Should I submit the correct information to the state so my descendants aren’t as confused as I was?

A: That would be a thoughtful service to future genealogists — but it might not be easy. Every state has its own rules regarding corrections to birth certificates, so you should consult with the vital records office in the state where you were born. We checked with Arizona, for example, which is notable for making PDFs of historical birth and death certificates available online. There, making a simple correction to your own information — fixing a misspelling, such as “Micheal” for “Michael” — requires an affidavit from you and documentation from the first 10 years of your life establishing the corrected fact. If there’s a name change (i.e., your birth certificate reads “Michael John” but you go by “John” and want your record to match), you’ll have to go to court.

Fixing information on your birth certificate about either of your parents, at least in Arizona, requires you to supply the parent’s birth certificate from the issuing state. Arizona needs the original certificate, which will be copied and returned to you. Information that you’ve determined is incorrect through research not reflected on the person’s birth certificate may be difficult or impossible to correct on your own birth certificate.

A version of this article appeared in the November 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

Q: My grandmother was born in South Carolina in 1910—before the state began keeping birth records in 1915. But I’m pretty sure she had a passport. Didn’t you need a birth certificate for that?

A: Your grandmother may have applied for a “delayed birth certificate.” Many states—especially those in the South—were relatively late to adopt state-level birth registrations, which created a problem later in the 20th century when people needed such documentation to apply for passports, Social Security or railroad pensions. As a substitute, individuals produced other proof of age, such as census and voter records, school documents, naturalization papers, family Bibles and affidavits signed by relatives. The state then issued after-the-fact birth certificates.

The good news is privacy restrictions on delayed birth certificates are typically looser than for standard birth certificates. You might even be able to skip the state bureaucracy entirely: The Family History Library has 42 microfilm reels of South Carolina delayed birth certificates, and you can search the catalog at FamilySearch to see if your grandmother’s birthplace is included.

A version of this article appeared in the November 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

Q: I’m having difficulties getting a relative’s birth records because I live in a state that restricts vital records. I’m not an immediate family member, and thus not entitled to the record. Any suggestions?

A: You don’t say about when the ancestor was born, but many states loosen restrictions on records created more than 75 or 100 years ago. So first, double-check the rules where your ancestor was born. If older certificates are unrestricted, you may need to request the record from the state archives. Try these ideas, too:

Try to find someone who is a qualified family member of the person in the record, and ask if he or she will request it for you (or perhaps the person already has a copy). A relative may be able to help you connect with the person, or you can post to surname message boards.

See if you can get an uncertified copy of the record. Unlike a certified copy, an uncertified copy can’t be used for official purposes such as identification. The uncertified record also may contain a bit less information.

Look for a birth index in print, online or on microfilm. It’ll certainly have less information than the full record, but you can confirm the person’s name, place and date of birth, and maybe the parents’ names. To find printed or microfilmed indexes, check with the state archives and a local library. Also, run a place search of the FamilySearch catalog on the county of birth, then look for a vital records heading.

You may need to go to other sources for birth information. The person’s church may have recorded his or her baptism. Maybe there’s a family Bible entry or the newspaper announced the good news (check newspaper databases such as Ancestry.com’s or GenealogyBank’s, or visit the local library for microfilmed papers).

Military records, death certificates, cemetery records and the Social Security Death Index can provide birthplaces and dates. Remember that these records, created long after a person’s birth, are more likely to contain errors than a birth certificate.

Answer provided by Allison Dolan

Q: If someone was born aboard an immigrant ship traveling to America, how and where is the birth recorded?

A: In The Family Tree Guide to Finding Your Ellis Island Ancestors (Family Tree Books), author Sharon DeBartolo Carmack says babies born at sea are generally listed on the last page of a ship’s passenger manifest, or at the bottom of any page where the ship’s clerk could find room. When looking at online passenger manifests, you would need to use the controls for the record viewer to page through the list for your ancestor’s ship.

Strange markings in the margins next to a name are a clue to check the last page of a list, or the ship’s Record of Detained Aliens and Record of Aliens Held for Special Inquiry (these are on supplemental pages of the list, following the pages with the passengers’ names). See this Guide to Interpreting Passenger List Annotations for help deciphering unfamiliar notations on passenger lists.

Notations on the passenger list won’t always give you a clear indication that a passenger gave birth on board, though, so if you suspect such an event, scan the entire list for names added during the journey.

Parents could seek birth certificates for newborns once they arrived at their destination. That doesn’t mean they always did, particularly before state-mandated birth recording.

In modern times, when a birth or death occurs at sea or on an airplane, the birth is reported at the next port of call. Learn more about in-flight births and the baby’s citizenship here.

Answer provided by Diane Haddad

Q: I’m looking for an ancestor born before his hometown began keeping birth records. Would his birth be in the records of the midwife who delivered him?

A: It’s a long shot, but worth investigating. Though midwives’ records varied, they often contained medical notes on each birth and the names of the parents responsible for paying for the midwife’s services. When midwives retired or died, their records were often simply disposed of, but they occasionally ended up in some library or archive. Check local university and historical society libraries.

Also try searching the FamilySearch catalog for the place where your ancestor was born, and then scrolling the results under Vital Records. You can add the keyword midwives or midwife to your search. A similar search might succeed at the WorldCat online catalog of libraries worldwide World Cat, which now includes FamilySearch’s Family History Library (FHL). You’d need to borrow the records through interlibrary loan or (for FHL materials) through a local FamilySearch Center.

Midwives’ records may have been transcribed and published in a journal indexed in the Periodical Source Index (PERSI). You can search this index at many libraries through HeritageQuest Online, or on the subscription site Findmypast.com.

A version of this article appeared in the September 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

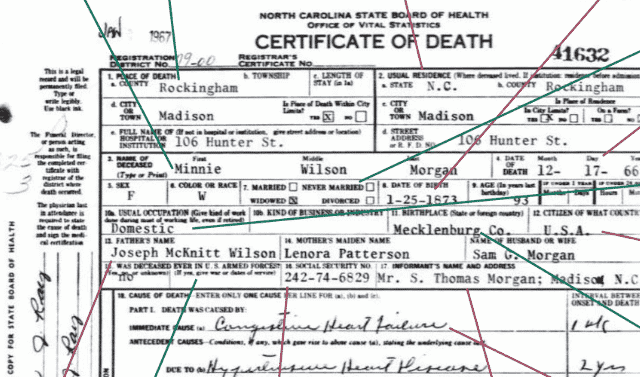

Q: My great-grandmother Ona May Boyer’s death certificate gives Washington as her birthplace on April 7, 1887. How can I find out where exactly she was born? I’ve documented older siblings born in Iowa and younger ones in Oregon.

A: Before Washington became a state in 1889, it was part of Washington Territory. Fewer records — including vital records — were created pre-statehood, which poses a challenge for genealogists. If a family lived in the territory for a short time, as yours did, it’s not easy to track them.

Censuses are a useful tool for territorial research. Even before statehood, the government kept tabs on territories’ residents, and many of those census records have been microfilmed. The Washington State Archives’ Historical Records Search includes an index to some 1887 records. My search for Daniel Boyer, Ona May’s father (named on the siblings’ birth certificates), unfortunately didn’t return any hits. But you can order the remaining 1887 censuses through the Family History Library in Salt Lake City for viewing at your local Family History Center.

When you’re stymied in your search for territorial records, evaluate what you know about the family and consider federal government records. For example, the Daniel Boyer family is on the 1900 Wayne County, Ind., census. Boyer, a widower, was born in August 1843 in Indiana — he’d have been the right age to serve in the Civil War. If he enlisted and later applied for a pension, he may have listed the places where he lived after his service. Check the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System index of more than 5 million soldier names. If you find Boyer there, look him up in Ancestry.com’s subscription-based Civil War pension index or in the National Archives’ General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934 (microfilm T288).

Answer provided by Connie Lenzen

A version of this article appeared in the August 2004 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: I thought a birth certificate, even a delayed one, was required to get a Social Security number (SSN). Yet, when I find SSNs for my deceased family members, I don’t always find birth certificates. Why?

A: When the US Social Security system was established in 1935, as individual didn’t need to show proof of birth to receive a Social Security number. In fact, the first SS-5 forms (used to apply for an SSN) weren’t turned in to the Social Security Administration (SSA), as they are now, but to an employer, a letter carrier or the post office. The newly formed SSA didn’t have local offices, so it contracted with the US Postal Service to handle SS-5 forms.

Proof of birth didn’t become an issue until an individual wanted to receive Social Security benefits. At that point, the person had to show he had indeed reached the age of 65 and was eligible to collect benefits. Although some of your relatives may have had birth certificates to submit, the SSA also accepted other records for verification of age.

The SSA had regulations — such as using records made as soon as possible after birth — when it came to “best evidence” documentation of age. In fact, the records you uncover through your genealogical research, such as Bible, baptismal and census records, were often accepted as proof of an individual’s age. It’s also possible that an ancestor applied for an SSN, but never requested benefits, and therefore, didn’t need to obtain a birth certificate.

Answer provided by Rhonda McClure

A version of this article appeared in the February 2004 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: My mother was born in Matanzas, Cuba, in 1914. She passed away in 1986. How can I obtain a copy of her Cuban birth certificate?

A: Cuban civil registration of vital statistics began in 1885; however, records are difficult to obtain because of strained diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba. The United States limits sending money and traveling to Cuba (though family visits are allowed), and Cuba forbids sending official documents to the United States.

One approach is to find a relative or friend in Cuba who’s willing to request a copy of the document from a civil registrar and pay the necessary fees. You’ll find civil registrar contact information at CubaGenWeb‘s Cuban Addresses & Telephones page.

If you don’t know anyone in Cuba, the US Interests Section of the Embassy of Switzerland in Havana can provide a list of Cuban law firms authorized by the Cuban government (attorneys there aren’t permitted to maintain private practices) that might be able to assist you. In order to pay any legal fees, you must apply to the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the US Department of the Treasury.

You also might try writing the church or diocese where your mother was baptized; you’ll find an address list on the CubaGenWeb site. Be sure to provide her full name, birthplace and date of birth. If she became a US citizen, request copies of her application from the Willow Bend Books).

Answer provided by Diane Haddad

A version of this article appeared in the February 2004 issue of Family Tree Magazine.