Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Marriage bonds — as in money, not the bonds of holy matrimony — were common in some states, particularly in the South, into the 18th century. They were posted in the county courthouse to help offset any costs of legal action in case the marriage was nullified. The groom and usually the father or brother of the bride posted a bond; if a woman posted bond, it may have been the bride’s mother because the father was deceased.

Licenses eventually replaced bonds in the 19th century. In some states, however, a license wasn’t required for a couple to be married, or the license might be recorded in a different jurisdiction from the marriage. For those states requiring licenses, keep in mind that couples sometimes took out a license or application but never made it to the altar. Make sure you follow through and look for further evidence confirming the marriage actually took place (a census enumeration, for example).

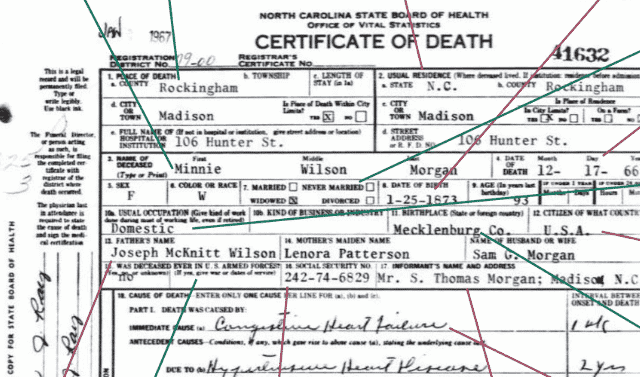

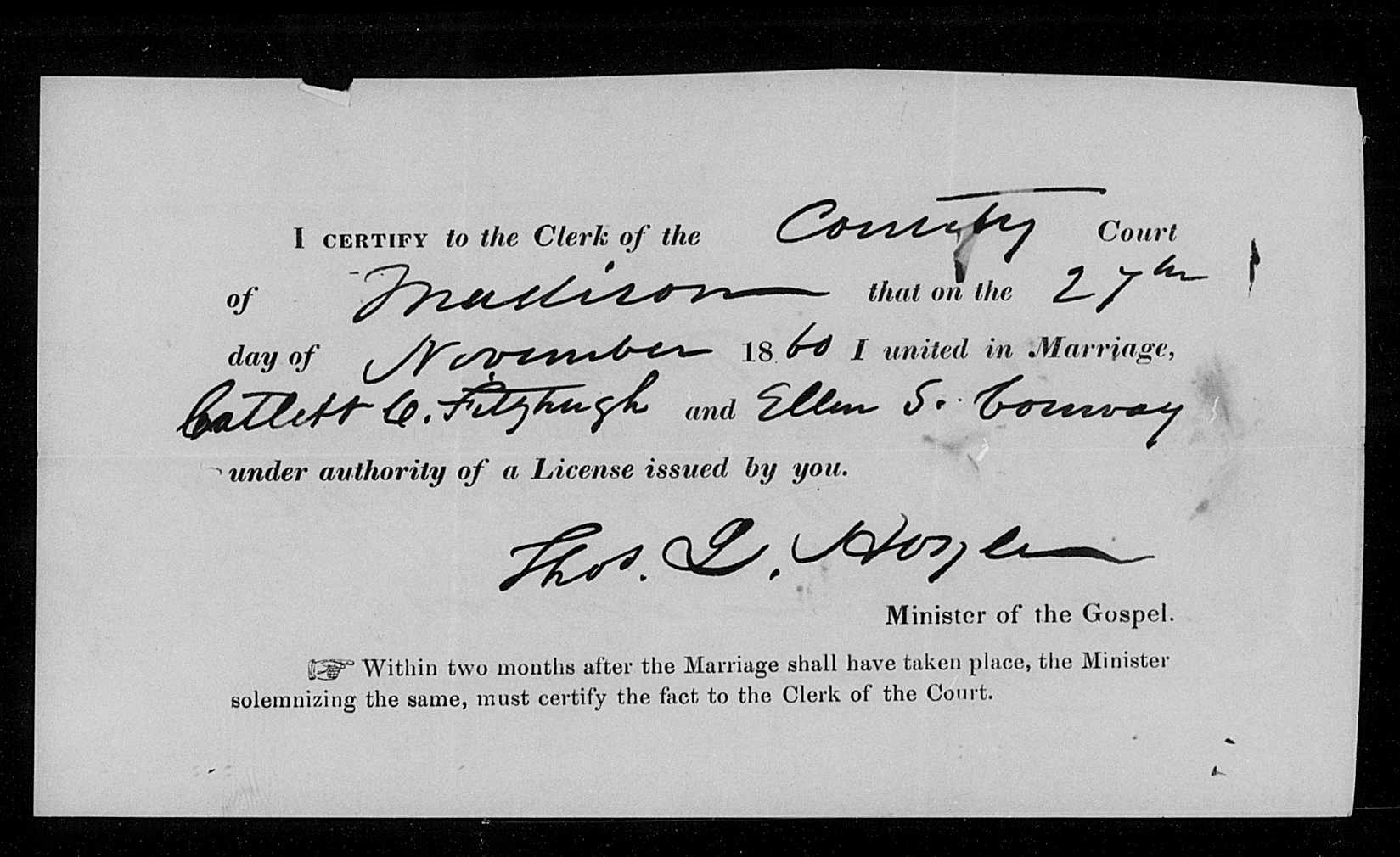

Where there are surviving marriage licenses, you may find a wealth of information on both the bride and groom, as this example of an 1860 license from Madison County, Va., shows:

Date of Marriage: 27 November 1860

Signed by Catlett C. Fitzhugh 10 November 1860. The marriage was performed on the date specified above.

Place of Marriage: at the residence of B.F.T. Conway, Madison County

Full Names of Parties Married: Catlett Conway Fitzhugh and Ellen Somerville Conway

Age of Husband: 29 years

Age of Wife: 22 years

Condition of Husband (Widowed or Single): Single

Condition of Wife (Widowed or Single): Single

Place of Husband’s Birth: King George County, Virginia

Place of Wife’s Birth: Madison County, Virginia

Place of Husband’s Residence: Richmond City

Place of Wife’s Residence: Madison County, Virginia

Name of Husband’s Parents: James M. Fitzhugh and Mary F. Stuart

Name of Wife’s Parents: Battaile F.T. Conway and Mary A. Wallace

Occupation of Husband: Merchant

On the same date the license was taken out, Catlett and Ellen entered into a prenuptial contract, which included Ellen’s father, B.F.T. Conway, as the third party. This “prenup” wasn’t filed with the marriage records, but in the county deed books. According to the contract, Ellen was “possessed of and entitled to real estate and personal property of considerable value, the personal estate consisting of slaves, debts, legacies and money.” This property and any she would inherit from her father were put in trust with Catlett for $1 for her use and benefit. She could dispose of all or any part of her property by will or otherwise, and it wasn’t subject to any debts Catlett incurred. The property would pass to Ellen’s children or their heirs, but if she had no children, the property was to pass to Ellen’s blood relatives, “in the same way as if she had not married the said Catlett C. Fitzhugh.” This was during a time when married women had few, if any, rights. Once a woman married, all of her property — from land to slaves to jewelry to the clothes on her back — became her husband’s. But because of this prenuptial agreement, the property Ellen received from her father was hers to do with as she deemed fit.

Courting, bundling and bridal abduction

So how did your ancestors meet and marry? Was he older than she or vice versa? By how many years? Was he someone she’d known for a long time? Was he a distant cousin? What were their expected roles in marriage? How did husbands and wives treat each other? David Hackett Fischer’s Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (Oxford University Press) and other social histories offer a sampling of many early American courtship and marriage customs. Here are a few examples:

Colonial English and “bundling”

The Puritans brought to New England many customs from England, but they rejected other traditions. Marriage, for instance, was no longer a religious ceremony, but a civil one, so if the terms of the union were broken, the marriage could be ended by a divorce. And instead of arranging marriages, the Puritans felt the couple should give their free consent. Love was considered a prerequisite of a happy marriage, so courtship customs were designed to allow couples some privacy.

One such custom was known as “bundling.” The prenuptial couple was allowed to share a bed, but a “bundling board” was placed between them. The young woman might also wear a “bundling stocking,” which fit snugly over both her legs like a large sleeve. Both men and women enjoyed this custom, as a contemporary song about bundling illustrated:

Some maidens say, if through the nation, Bundling should go quite out of fashion, Courtship would lose its sweets; and they Could have no fun till wedding day. It shant be so, they rage and storm, And the country girls in clusters swarm, And fly and buzz, like angry bees, And vow they’ll bundle when they please. Some mothers too, will plead their cause, And give their daughters great applause, And tell them ’tis no sin nor shame, For we, your mothers did the same. Some really do, as I suppose, Upon design keep on some clothes, And yet in truth I’m not afraid For to describe a bundling maid; She’ll sometimes say when she lies down, She can’t be cumber’d with a gown, And that the weather is so warm, To take it off can be no harm: The girl it seems had been at strift; For widest bosom to her shift, She gownless, when the bed they’re in, The spark, nought feels but naked skin. But she is modest, also chaste, While only bare from neck to waist, And he of boasted freedom sings, Of all above her apron strings.

“A New bundling song: or A reproof to those young country women, who follow that reproachful practice, and to their mothers for upholding them therein,” Isaiah Thomas Broadside Ballads Project

Southern Colonial planters

More than half of all Southern women married someone who lived within five miles of their home. Cousins often married, which tightened the family circle and kept the wealth in the family. Many women preferred to marry a familiar cousin rather than a stranger.

Virginia, a colony primarily established by unmarried men, suffered a shortage of eligible women into the 18th century. When a man found a suitable partner, he needed both his father’s and her father’s consent, especially if the young man was from a family of means. If his father approved, then negotiations would begin with the potential bride’s family. The bride’s dowry averaged about half of what the groom brought to the marriage. Weddings typically took place in the afternoon in the bride’s home, with the local minister presiding. A feast and dancing followed the ceremony and lasted until the next morning.

Scotch-Irish

While the Puritans often courted and married for affection and the Virginia planters wed based on social status, the Scotch-Irish had a unique custom based on their ancestral folkways. Bridal abduction — either voluntary, involuntary or a mock ritual — was a custom into the 18th century. President Andrew Jackson abducted his wife, Rachel Donelson Robards, who went voluntarily. The problem was that she was married to another at the time, albeit unhappily, and Jackson was arrested. (This was well before the election!)

Colonial Quakers

Though Quakers believed marriages should be based on true Christian love, this didn’t necessarily mean romantic or sexual attraction. True love was possible only between those of the same faith.

Proper Quaker marriages required several stages before the ceremony. Aside from getting parental consent, couples had to jointly announce their intention to marry before both the women’s and men’s church services (“meetings”). After a waiting period, usually two meetings, the men’s meeting formally approved or disapproved the union. Invitations to family and friends announced the wedding. The “ceremony” resembled a typical meeting for worship: Members arrived, took their places and sat quietly. Those who were moved to speak did so. Toward the end of worship, the betrothed couple rose, declared their agreement to marry, exchanged promises and sat down again. Then everyone went home. All or most guests at Quaker weddings signed the marriage certificate as witnesses, especially relatives.

No matter what the time period, culture or ethnic group, with additional research into courtship and marriage customs, you can find out how your ancestors probably behaved in the days of their betrothal and as they walked down the aisle. That’s as important a part of discovering your family history as the names and dates.

Related Reads

A version of the article appeared in the June 2000 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: November 2024

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for site to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.