Have you ever considered that a tree’s root system is much more extensive than its combined trunk, branches and leaves? The same is true of family trees. On your family tree, you have more ancestors than you have parents, siblings and children. Discovering your family roots means uncovering those ancestors — solving the puzzles of genealogy.

Maybe you like working puzzles or outguessing detectives in mystery stories; genealogy is another form of puzzle and mystery. Or maybe you enjoy reading historical novels; genealogy is a family-made adventure in history, sometimes better than a novel. If you’re curious about your family history, and combine this curiosity with the challenge of finding solutions plus the adventure of history, you’ll love “doing genealogy”

That involves:

- Looking for ancestors

- Trying to identify the events, names, places, dates and relationships that shaped their lives

- Trying to learn about their place and experience in the history and geography that surrounded them.

“Doing genealogy” means starting with yourself and working back, one generation at a time, toward the unknown. Sometimes, the identification process is as easy as looking in a family Bible, interviewing older relatives and reading newspaper obituaries.

At other times, discovering the names of the next generation of ancestors is not so straightforward. That’s when you need to probe deeper for clues, ask more questions and look for more cousins. You have to study everything you can find and try to draw logical, reasonable and documented conclusions. Eventually, all of us hit the proverbial brick wall in every family — that’s a given. It’s often possible, however, with enough curiosity and determination, to get around those walls. Every success, large or small, keeps you in the hunt for that next ancestor. A dedicated genealogist will go to great lengths to prove one great-grandmother’s maiden name or one great-grandfather’s real birthplace.

Why? We’re curious, and we want the best possible answer to the puzzle. Little good it does if we accept the wrong ancestor. Little good comes from working a jigsaw puzzle where the pieces almost fit. In a jigsaw puzzle, it’s a funny-looking cat that ends up with a church spire where its tail should be, just because the colors are the same. In genealogy, it’s a funny-looking family where names match but the mother is 30 years old, the father is 8 and the son is 22.

Genealogy begins at home

Start under your own roof, before even the first visit to the library. Here are four keys to getting started on your own puzzle:

1. Vital statistics are vital. First, gather names and vital statistics: birth, marriage and death dates and places. Include your immediate family, parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. This information is often tucked away in boxes under the bed, in the attic or in Aunt Hattie’s old trunk. It could be in scrap-books, family Bibles or birth, marriage and death certificates.

Interviewing relatives is another way to discover information on several generations. Ask Grandma about her parents and grandparents. Uncle Henry might supply names of children who died young, whom no one else thought to mention. Aunt Clara may fill in gaps on Aunt Sally’s family, with whom everyone else has lost contact. The more different the contributions, the more thorough the picture. You may also get discrepancies: two different marriage dates for Uncle Albert and Aunt Jane. Keep both. That’s something to resolve as you research.

2. Focus your search. When you’ve gathered names, relationships and vital statistics for several generations using materials at home and from relatives, choose a focus ancestor for concentrated study. Maybe it will be a grandparent you were named after, or a great-grandparent about whom you know very little.

You had eight great-grandparents, four couples. Each couple probably created records of the kind found in courthouses or archives. These records may contain your missing information. They also may lead you to the parents, grandparents and other forebears of your focus couple.

Try to focus on one family at a time. Otherwise, too many names dilute the search and you don’t really study each family It’s in-depth study that leads to breakthroughs.

3. Chart your findings. Over the years, genealogists have developed helpful charts for displaying vital statistics and relationships. Most genealogy computer software allows users to print out a variety of nice-looking chart formats (see page 48 and page 69 for more on software). A book with many kinds of pre-printed forms for the genealogist is The Unpuzzling Your Past Workbook (Betterway Books, $15.99). Or you can download blank versions of the forms on these pages, and many more here.

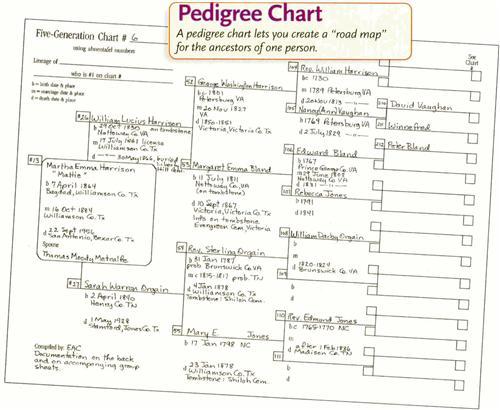

One basic genealogy form is the pedigree chart (below). This multi-generation chart reads backward in time to show the ancestors of one person. It’s a good reference, something like a road map of ancestor names, dates and places. Most pedigree charts show four or five generations, although versions are available for naming many more.

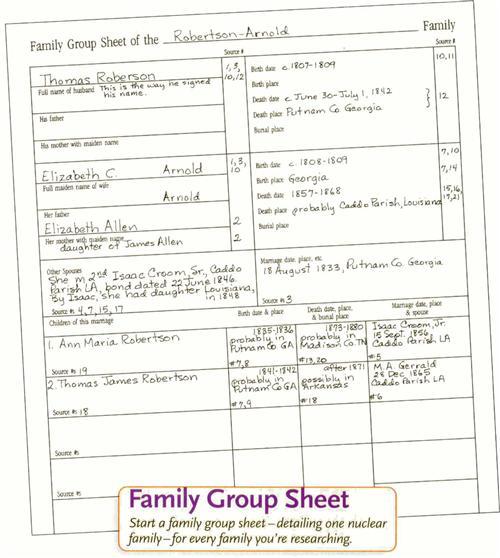

Another useful chart is the family group sheet (opposite page), a record of three generations. Broader in scope than the pedigree chart, it details one nuclear family: parents and their children, with names of grandparents. You should start one of these charts for every family you study: yourself as both child and parent, your siblings and their families, your parents as children, their siblings and families, and so forth.

These two charts are not meant to be filled out as you research. They don’t take the place of research notes. Instead, they’re the products of research: vital statistics, names and relationships that are established and shown to be correct.

4. Get organized. Genealogy research consists of two basic components: methods and sources. Part of good methodology is getting and staying organized. This means deciding how to record your research notes and how to file them so you can find them easily There’s no right or wrong way: Do what works best for you. There are probably twice as many ways to organize as there are genealogists, because nearly everybody changes procedures at some point.

Some people work best with file folders stored in boxes or cabinets. Others work best with three-ring binders housed in bookcases. Many use a combination of these. Some find index cards useful for master lists. Most genealogists agree, however, that spiral notebooks aren’t a good choice and the dining room table isn’t the best option for holding our stuff. Yes, everybody usually tries the table and learns that Thanksgiving dinner or Mother’s Day brunch creates a real kink in the filing system.

Whether using folders or binders, most genealogists keep all papers pertaining to a given ancestor or couple in one folder or notebook. Even those who store notes and documents in file folders at home may use notebooks for research.

Many genealogists sort research notes first by surname or individual, then by location, then by topic or type of source where information is found. For example, let’s say your focus ancestor is named Polk, so you have a notebook dedicated to Polk family research. When you find this ancestor in North Carolina and then, earlier in life, in Delaware, you divide the notebook into a section for each state. If the ancestor lived in more than one county in North Carolina, you’ll probably subdivide the North Carolina section by county. Behind the county dividers are subdivisions for land, marriage, cemetery and other kinds of records. As notes accumulate, a separate binder may be needed for each state. The same ideas can apply to file folders.

Another important but easily overlooked aspect of organizing is consistency in the size of paper you use. Standard 8½×11-inch paper works best. If you can avoid using notepads and backs of envelopes, you’ll have better luck keeping up with your notes.

Some researchers prefer taking notes on laptop computers instead of paper. Others transcribe all their notes to the computer when they return home from researching. Whether paper or electronic, your notes need to be filed for later study by name, location and source.

You may try several filing ideas to determine what works best for you. Whatever you choose needs to be easy for you to maintain and use — after all, unpuzzling your past is an adventure that may span many years.

Doing research right

Some basic research techniques and tips can help make sure that your puzzle pieces come together. Here are nine principles to keep in mind as you start digging into your roots:

1. Names. Always look for names: full names, middle names, parents’ names, spouses’ and children’s names. Names can be important clues to the past. Family surnames, for example, have long been adopted as given names: Blalock, Vincent, Major and so on. Middle names can also be clues, often to the maiden name of a mother or grandmother — but only clues, because there’s no guarantee that Hardy Green Carter had an ancestor named Hardy or Green. If Hardy and cousins had the middle name Green, there’s a reason. You’d want to find out why this pattern exists and what it may mean in discovering your ancestors.

Regardless of names in vogue at any given time, plenty of children in the English-speaking world (perhaps too many from the genealogical point of view) have been called Mary, Sarah, Elizabeth, James, John and William, especially when these were “family” names. You’ll become acutely aware of names when trying to sort out ancestors. Is the William Smith who keeps appearing in the county records one man or three? Did Samuel Stone have one wife named Mary or two? Just because the name is the same, you can’t assume it’s your ancestor.

For female ancestors, search for maiden names because they help identify the parent generations; use maiden names on charts instead of married names. When genealogists speak of the children of James Brown and Melissa Gray, we’re not implying that the couple had children out of wedlock; we’re identifying the wife’s maiden name.

Expect spelling variations in names. If one brother dropped the e from the end of his surname (Brown) and the other brother kept the e (Browne), you have to look for both. A person in the records with or without the e could belong to either branch. Remember, many of your ancestors couldn’t read and write, or spell their own names. Regional accents and accents of those for whom English was a second language also meant that clerks didn’t always understand spoken names and had to guess the spelling. Clerks wrote down what they heard and sometimes spelled words phonetically and creatively: Right for Wright and Eldridge for Heldreth.

Before working on a focus ancestor in documents and publications, list ways the name might be pronounced and spelled. Look for all the variations in indexes and records as you research. Don’t ignore something just because the name is spelled differently from what you expect.

2. Family stories. Interviewing relatives and friends is a good way to collect family stories and oral traditions. Some are simply fun and add a human quality to the family history. Others have a genealogical character: where folks came from and when, who a great-great-grandparent was, how one ancestor became the hero of a certain battle, how we are descended from a certain general or president. These tales often contain some truth, but many are simply a matter of “creative remembering.” The “hero” may have participated in that battle, or the family may have lived near the battlefield when the “hero” was five. The general or president may have the same name as an ancestor, with no kinship whatsoever.

Your job is to use such stories as clues for research to try to determine the truth.

3. Cluster genealogy. Your ancestors didn’t live in a vacuum but in a family, an extended family and a community They lived, worked and worshipped with, fought beside, served on juries with, did business with, married and were buried near relatives, friends and neighbors. To trace your ancestors successfully, you’ll eventually need to develop and study a cluster of their relatives and associates. Make a habit of collecting information on other known relatives, especially siblings, and those suspected of being related.

4. Networking. Finding cousins, even distant ones, is often a way to increase your knowledge of a focus ancestor. Many researchers use genealogical periodicals and the Internet, with its thousands of genealogy Web sites, to find other people working on the same surname, the same ancestor, or the same county. Computerized databases and electronic products contain millions of names, and many genealogists search them for ancestors.

The answers found in such periodicals, Web sites and databases vary greatly. Much depends on the quality of work done by the people who compiled the information. The best researchers consider the information they find in this way as clues. They try to track down the original source of the information, evaluate it, compare it with other sources, and be convinced of its accuracy before accepting it. Less-cautious researchers swallow the whole, even if it says that two siblings were born four months apart and a year after their mother died.

Many such databases give “family trees” going back a thousand years or more. These are usually more wishful thinking than fact. Even though people may want Charlemagne as an ancestor, proving that he actually was will be next to impossible. It’s much better to work carefully backward through fewer generations and know that what you have is solid, in-depth, documented and still interesting.

5. Continuing education. Genealogists have many opportunities to learn as they go. You can join genealogical societies, including ones in the state or county where your focus ancestors lived. You can attend local, regional and national conferences. You can begin to assemble your own library of reference books, or read genealogy periodicals. Through societies, at conferences and research facilities and on the Internet, you can meet, share with and learn from other genealogists.

6. Sources and evidence. Sources abound. The ones genealogists love most are the sources that give a direct statement of a genealogical fact — a name, date, place or relationship: “I,John Stephens Barker, give to my grandson John Barker Tomlinson the farm where I now live, at Pearson’s Crossroads.” “I, Stanley Griggs, consent for my daughter Melissa Jane, age 15, to marry James Roberts.” These kinds of statements are often found in such sources as land, military, probate, marriage and court records.

When you can’t find direct evidence of this kind, look for clues again. Investigate sources that may lead you indirectly to the facts. Genealogists frequently use such “circumstantial evidence” to establish relationships. But you must not jump to conclusions. Your goal is to establish genealogical facts from the best available sources, using as many as it takes to make a convincing “case.”

The best sources are usually the ones closest in time to the events they report, especially first-hand accounts. A clerk’s recording of a marriage, land transaction or will is usually the closest we can come to these events. But even these official records can contain copying errors. Published books are at least one more step away from the most original record and therefore have added potential for human error. So you can’t automatically accept the handwritten or printed word as absolute truth.

7. After “home work,” then what? You won’t find all your answers at home, or in any one place. After your initial “home work,” you should visit genealogy collections in libraries, history and reference sections of university libraries, cemeteries and courthouses.

You might start your outside research in the federal census records. Every 10 years since T790, the United States government has counted the population to apportion seats in the House of Representatives. Census records through 1920 are widely accessible on microfilm, and some are already on CD-ROM. Ask about availability at your local library or at a Family History Center operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (You can find the center nearest you online here.

Information in the census records varies. The most comprehensive for genealogists are those for 1850 and afterward because they name members of free households and indicate ages, birthplaces, occupations and other details. Like other records, they can contain mistakes and omissions, but they’re great and fascinating resources.

Genealogy books and microfilm copies of newspapers and county records are sometimes available on interlibrary loan through local public libraries. Many state historical societies or state libraries lend these kinds of sources within their own state. One large rental library is the American Genealogical Lending Library, part of the Heritage Quest genealogy-publishing company (800-760-2455). Some societies, including the National Genealogical Society (703-525-0050) and the New England Historic Genealogical Society (617-536-5740), allow members to rent books from the society library More and more actual records are also appearing on the Internet.

If you have a Family History Center within reach, you have access to the resources of the church’s monumental Family History Library in Salt Lake City. Renting microfilm and microfiche is easy, and coverage is virtually worldwide. Volunteer staff at the centers can also show you how to use their computerized and electronic databases. Recently, many of the Family History Library’s resources have also been made available via the FamilySearch site.

8. Plan, research and review. Written plans for research help keep you on target. From the unknowns in your information, decide what you want to look for and list your research questions before you go to research. Other tips:

- Don’t try to reach back too quickly by skip ping a generation.

- Be open to discarding preconceived ideas and oral tradition.

- Follow up on leads and clues. A valuable clue, for example, might be a seemingly unimportant list of jurors with your ancestor’s name on it. To the genealogist, this proves the ancestor was alive and in that place on that date.

- Think as you research: Is this the right time and place for this ancestor? Does the information make sense for this ancestor? What makes me believe this really is my ancestor?

- Each time you research, review and analyze what you have found as you plan what to do next. Did you get any direct answers? What clues did each record give you? What conclusion do the facts support? Or what further research do you need to do before you can reach a conclusion?

9. How do you know? As you research, make note of where you find each piece of information. This process of documenting your research is essential. If you found Aunt Mattie’s birthdate on the back of her baby picture in Grandma’s handwriting, say so. If Grandpa’s death certificate names his parents, note it. For any source you use, write down as much identifying information as possible, including page numbers. You need enough for a complete footnote or bibliography entry (remember those from back in school?).

Why bother? First, you may need to look at the information again later to check details. Second, others may want to look at the same source to see whether it helps their research. And finally, you need to be able to defend your answer to the questions, “How do you know?” and “Where did you get that?”

Happy hunting!

Whether or not you’re new to genealogy, these suggestions will help you research within your family or in public records. Genealogists who are focused, organized, cautious, thorough, continually learning, thinking as they research, explicit in documenting their work, and pa tient are more successful. They’re the ones who get the most out of — and have the most fun — unpuzzling their past.