Every town has a history, but some cities make visitors feel as though they’ve traveled back in time as well as across the country. In North America, these classic cities feel almost European (never mind that European cities have more than a few centuries on even our oldest burg). History clings to their narrow, winding streets like Spanish moss, and heritage imbues their stately homes and monumental architecture with the grace of generations past.

We’re blessed with many such places across the continent, but these are five of our favorites. That European quality is particularly evident in cities such as Montreal and New Orleans. Others — Richmond, Charleston — remind us of the bygone world of the Old South. And San Francisco uniquely unites the rugged West with the charms of the Victorian era.

Whether you’re visiting for a vacation, to delve into your family’s history in one of these places or a bit of both, these cities let you step back into yesteryear as easily as crossing the street.

Vive L’histoire! Montreal

The largest French-speaking city in North America and the second-largest city in Canada, Montreal takes its name from Mont Royal, the mountain on the island where the city sits. It was named that in 1535 by explorer Jacques Cartier.

Old Montreal

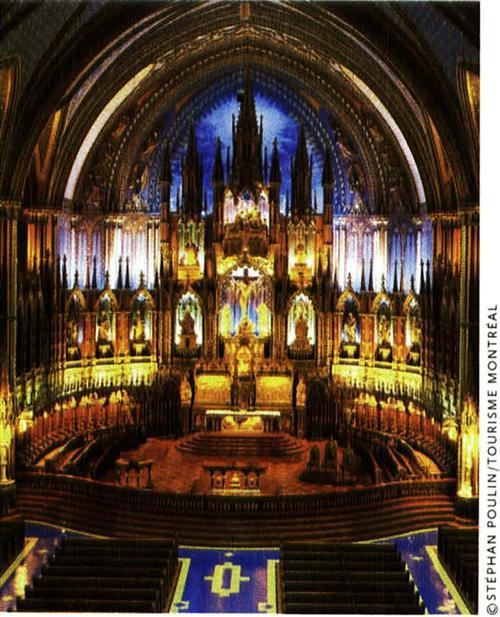

The city dates from May 17, 1642, when a group of 50 French settlers founded VilleMarie on a tip of land, beside a stream flowing into the St. Lawrence River, in what’s now part of Old Montreal <vieux.montreal.qc.ca/eng/accueila.htm>. This once-walled section of Montreal was declared a historic district in 1964. The oldest remaining building in the city dates from 1685, built and still owned by the Sulpician order of the Roman Catholic Church. Other historic buildings include Notre-Dame de Montreal <www.patrimoine-religieux.qc.ca/bndmtl/bndmtle.htm>, constructed from 1824 through 1829 (it replaced an earlier church), and the 10-story New York Life Building, Montreal’s first skyscraper, erected in 1888.

Within the district lies Pointe-à-Callière, the Montreal Museum Of Archaeology & History (350 Place Royale, 514-872-9150, <www.musee-pointe-a-calliere.qc.ca/indexan.html>). The museum is actually several buildings, including a modern museum, Montreal’s first customs house (1838) and the Youville Pumping Station (1915). They’re connected via an underground archaeological crypt. Here you’ll see the remains of an old cemetery, the stream that once flowed here and the fortifications that guarded the city years ago. You can also watch a multimedia show, see virtual figures from history and have lunch at the restaurant inside. Pointe–à-Callière opened in 1992, after about 10 years of archaeological digs on the site.

Notre-Dame Basilica

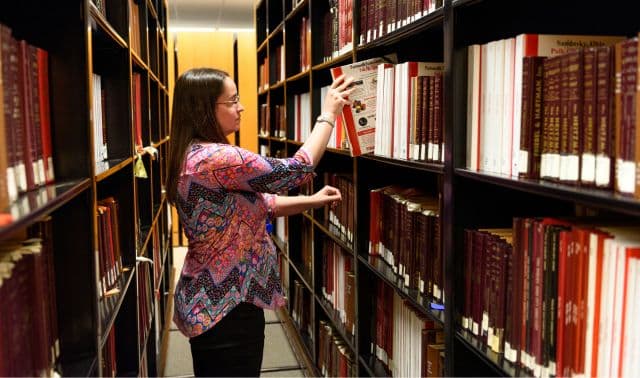

If you’re here for family history research, start with the Bibliotheque Centrale (1210 Rue Sherbrooke Est, 514-872-5923, <www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca/biblio/pageacc.htm>) and its online catalog search, Gulliver <gulliver, ville.montreai.qc.ca>. The Bibliotheque Centrale is one of three libraries being merged into the new Bibliothèque nationale du Quèbec (2275 Holt, 514-873-1100, <www.bnquebec.ca/en/quien/quipresenten.htm>). Scheduled to open in late 2003, it’s a public library dedicated to collecting and preserving Quebec’s and Montreal’s documentary heritage. Its 4 million holdings encompass 1 million books, plus newspapers, government publications, private papers and photos. Some items have been digitized and are on its Web site.

WHERE TO GO, WHAT TO SEE…

The Archives de Montreal (275 Rue Notre-Dame Est, 514-872-2615 and 514-872-1173, <www2.ville.montreai.qc.ca/archives/archives.htm>) has photographs and documents relating to the city’s past.

The Stewart Museum (20 Chemin Tour de l’Isle, Île Ste-Hélène, in the middle of the St. Lawrence River, 514-861-6701, <www.stewart-museum.org/map.htm>) deals with the history of Canada and its relationship with western European civilization, especially exploration and colonization. It has representative collections of the 16th through 19th centuries.

For a taste of how your ancestors traveled, make a visit to the Canadian Railway Museum (120 Rue St-Pierre, 450-632-2410, <www.exporail.org/musee/museeCRM.htm>) in suburban St. Constant on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River. It has the largest collection of railway equipment in Canada, including steam and diesel engines, a variety of passenger equipment and trolleys. Short train and trolley rides are available.

Another transportation-related attraction within Montreal is the Lachine Canal (514-283-6054, <www.parcscanada.gc.ca/parks/quebec/canallachine/en>). The canal opened in 1825; it was enlarged in 1848 and again in 1884. It closed in 1970, after the completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway led to a decline in traffic. Earlier this year, however, the canal reopened to pleasure craft following a multimillion-dollar restoration. It once formed the industrial heart of Montreal and the entrance to the Great Lakes for shipping. The recreational trails now lining its banks are popular for walking and cycling.

For a sweeping view of the city and a nice relaxing walk, visit Mont Royal Park <www.lemontroyal.qc.ca/en_index2.html>. Mont Royal is the dominant feature of Montreal, and the park marks its 125th anniversary this year. It was designed by Frederick Law Omstead, who also conceived New York’s Central Park. Easily reached by public transit, the park offers opportunities to walk trails, enjoy nature and see the city from the highest point on the mountain. Smith House, which dates from 1858, serves as the park’s visitor center.

Montreal has an excellent transit system. The STM (514-280-5100, <www.stm.info/English/a-somm.htm>) operates the city’s bus, subway and commuter rail. Montreal’s subway, called the Metro, was patterned after the Paris Metro.

Remember that Quebec is a French-speaking province; while most services are in both French and English, some aren’t. For example, the Web sites for the archives of Quebec, the Montreal archives and the Montreal library are only in French. Announcements on the STM are exclusively in French, too.

Mont Royal Park

As you’d expect in a city with a French accent, Montreal has a variety of fine restaurants. Here’s a small selection:

• Le Fripon (436 Place Jaques-Cartier, 514-861-1386, <www.bar-resto.com/lefripon.htm>): Fine French cuisine in the heart of Old Montreal.

• Moe’s Deli & Bar (3950 Rue Sherbrooke Est, 514-253-6637, <www.bar-resto.com/moes> : Well-known eatery across from the Olympic stadium and near the botanical gardens.

• O’Donnell’s Pub (1224 Bishop St., 514-877-3128, <www.bar-resto.com/odonnell/index-e.htm>): Irish food and entertainment.

For accommodations in the downtown area, try the following hotels:

• Best Western Ville-Marie (3407 Rue Peel, 514-288-4141, <www.hotelvillemarie.com/index_en.html>): At the foot of Mont Royal.

• Hotel St-Denis (1254 Rue St-Denis, 514-849-4526, <www.hotel-st-denis.com>)

• L’Abri du Voyageur (9 Rue Ste-Catherine Ouest, 514-849-2922 <www.abri-voyageur.ca/english> : A good option for those on a budget.

If you prefer a bed-and-breakfast, contact the Downtown B&B Network (800-267-5180, <www.bbmontreal.qc.ca>).

Old Virginny Richmond

History records that in 1609, Capt. John Smith purchased land from Chief Powhatan and called the settlement “None Such.” That settlement eventually evolved into Richmond, but today there still is nonesuch place as this capital of Virginia and former capital of the Confederacy.

Where else can you drive along one of America’s most beautiful avenues and gaze up at imposing memorials dedicated to war heroes from the losing side? Monument Avenue takes its name from the stately statues of Confederate Gens. Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart and President Jefferson Davis. African-American tennis champion Arthur Ashe, a Richmond native, also is represented.

The James River, which offers up to Class V rapids, gives Richmond claim to the only urban Whitewater run in the United States. The city also has the largest intact Victorian neighborhood (Fan District), oldest continuously operated farmers’ market (17th and Main streets) and second-oldest working state capitol in the nation. The Capitol’s designer, Thomas Jefferson, lends his name to the National Historic Landmark Jefferson Hotel (101 W. Franklin St., 804-788-8000, <www.jefferson-hotel.com>), whose famous “guests” included alligators that resided in the lobby’s reflecting pools until 1948. This grandest of Richmond hotels also features a lavish marble staircase, which many locals proudly claim was the model for the one in Gone With the Wind.

There also may be nonesuch place for family historians, especially if your roots run deep in the Old South. Begin at the Library of Virginia (800 E. Broad St., 804-692-3500, <www.lva.lib.va.us>), the repository for all the commonwealth’s records, from the colony’s founding to today.

Richmond skyline

At the Virginia Historical Society (428 N. Boulevard, 804-358-4901, <www.vahistorical.org>) you can relive Virginia’s rich history by wandering through the museum’s extensive galleries.

Most people visit the Museum of the Confederacy (1201 E. Clay St., 804-649-1861, <www.moc.org>) to view the world’s largest collection of artifacts associated with the Confederacy. The Washington Post says the neighboring White House of the Confederacy, where Jefferson Davis lived during the Civil War, “probably is second only to Mount Vernon among restorations of historic American dwellings.”

For still more Civil War history, visit the Chimborazo Visitor Center (3215 E. Broad St., 804-226-1981), where a hospital complex built in 1861 treated more than 75,000 soldiers. This also is a great place to grab tour maps of nearby battlefields. Historians estimate that one-fourth of the Civil War’s battles and more than half of its casualties took place within a 75-mile radius of Richmond.

WHERE TO GO, WHAT TO SEE…

Another heritage-filled stop is the Valentine Richmond History Center (1015 E. Clay St., 804-649-0711, <www.valentinemuseum.com>). The museum’s decorative and fine arts, industrial artifacts and archaeological finds document Richmond’s past. While the majority of the center’s holdings are not on display, books, photos, diaries and letters are available for research by appointment.

In its prime, Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood was called the cultural mecca of Southern black society and the Wall Street of black America. Today, it’s home to the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia (00 Clay St., 804-780-9093, <www.blackhistorymuseum.org>), which collects oral and written records, photographs and other artifacts commemorating the lives of African-Americans.

The Beth Ahabah Museum and Archives (1109 W. Franklin St., 804-353-2668, <www.bethahabah.org/museum/museum.html>) highlights Jewish culture in Richmond since 1789; it also operates Hebrew Cemetery (Fourth and Hospital streets), which includes a section that holds Confederate soldiers — -thought to be the only Jewish military cemetery outside Israel.

Another notable burial ground is Hollywood Cemetery (412 S. Cherry St., 804-648-8501, <hollywoodcemetery. org>). Movie stars aren’t buried here (the cemetery takes its name from surrounding holly trees), but there are plenty of famous names nonetheless, among them Presidents James Monroe and John Tyler, founding father John Randolph, Jefferson Davis and J.E.B. Stuart. A 90-foot granite pyramid completed in 1869 serves as a memorial to the estimated 18,000 Confederate soldiers buried nearby. With scores of intriguing memorials sitting on a bluff overlooking the James River and Belle Isle, the cemetery is one of Richmond’s most beautiful and serene spots. St. John’s Church (2401 E. Broad St., 804-649-7938), Richmond’s oldest, was the site of Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” speech. This most famous of patriotic pep talks is re-enacted each Sunday at 2 p.m., Memorial Day through Labor Day. Also take time to admire the architecture and stroll the statue-laden grounds around Capitol Square (Ninth and Grace streets), or join a free tour of the Virginia State Capitol (804-698-1788).

Don’t pass up a visit to Maymont (2201 Shields Lake Drive, 804-358-7166, <www.maymont.org>), a 100-acre country estate along the James River. Mansion tours are available by reservation, but simply wandering the grounds is one of the truest pleasures in Richmond. Attractions include lovely Italian and Japanese gardens, a petting zoo and wildlife habitats containing animals native to Virginia.

If you prefer a tamer setting, visit the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (2800 Grove Ave., 804-340-1400, <www.vmfa.state.va.us>). The museum houses one of the South’s largest art collections and features works by Degas, Monet and John Singer Sargent among others.

Don’t miss whatever film is playing at the Byrd Theatre (2908 W. Cary St., 804-353-9911). Known fondly as Richmond’s movie palace (you’ll see why when you step inside), this National Historic Landmark opened in 1928. Consider yourself especially fortunate if you’re in town on a Saturday night, when the movie is preceded by a song or two performed on the mighty Wurlitzer organ that rises out of the orchestra pit. Splurge and sit in the balcony for an extra dollar ($2.99 total).

Another tip: Purchase a Richmond Pass for $15. Available at city visitor centers and all participating attractions, it covers admission for your choice of any five of 17 museums, historic homes and gardens. You’ll likely have to do some driving in Richmond, but if you’re visiting on a weekend from June to November, use the Richmond Cultural Connection (804-783-7450), which shuttles between various attractions, shopping spots and restaurants. One dollar (free for Richmond Pass holders) pays for an entire day of unlimited transfers.

As for where to kick off your shoes, the Commonwealth Park Suites Hotel (901 Bank St., 888-343-7301) across from Capitol Square and the Richmond Marriott (500 E. Broad St., 800-228-0265) both are within three blocks of the Library of Virginia. The Linden Row Inn (100 E. Franklin St., 800-348-7424) offers reasonable rates that include a deluxe continental breakfast, afternoon wine and cheese, downtown transportation and free use of a YMCA. If you want to live like a Virginia aristocrat, stay at the five-diamond Jefferson Hotel and eat at its renowned restaurant, Lemaire (804-788-8000).

For great food at great prices, head to the Fan District, where top choices include the heaping helpings of baked spaghetti at Joe’s Inn (205 N. Shields Ave., 804-355-2282) and the spicy Southern delicacies at Southern Culture (2229 W. Main St., 804-355-6939). If you’re looking for something more upscale, head down to the cobblestone streets of Shockoe Slip, where Sam Miller’s (1210 E. Cary St., 804-644-5465) specializes in seafood. Another popular option is the Tobacco Co. Restaurant (1201 E. Cary St., 804-782-9555), a converted tobacco warehouse featuring Virginia-inspired specialties. Third Street Diner (218 E. Main St., 804-788-4750) isn’t known for its haute cuisine, but you can get breakfast 24 hours a day, and the cast of characters this downtown institution regularly attracts rivals even the most eccentric of family trees.

– Jonathan Rollins

Virginia Capitol

Old-Fashioned Southern Hospitality Charleston

A crown jewel of the South, Charleston has more church spires than skyline, more hospitality than hustle. Known as the “Holy City,” its religious relics — and dignified citizens — have survived three centuries of epidemics, fires, wars and hurricanes.

Perhaps that’s why graciousness is the everyday mood in this charming, antebellum spot, which offers (thank you very much) a heavenly heap of heritage sites.

Located near the hub of Charleston’s historic downtown, by the corner of Broad and Meeting streets, is the South Carolina Historical Society (100 Meeting St., 843-723-3225, <www.schistory.org>). Formed in 1855, it includes an extensive collection of rare manuscripts, books, letters, maps, journals and periodicals, as well as a photo archive of more than 40,000 images.

Just northwest of the historical society building, Charleston’s past comes to life at The Citadel Archives & Museum (171 Moultrie St., 843-953-6846, <www.citadel.edu/archivesandmuseum>). Arranged chronologically from 1842 to present, its permanent exhibits display the military, academic, athletic and social aspects of past cadets.

Charleston area

From The Citadel, go a few blocks south to visit the nationally recognized Avery Research Center for African-American History and Culture (125 Bull St., 843-953-7609, <www.cofc.edu/avery>), founded in 1865 and located west of the main campus of the College of Charleston. The center traces the heritage of South Carolina’s Lowcountry African-Americans and contains one of the best series of manuscript collections documenting the Civil Rights movement.

One of the best aspects of Charleston is its 181 churches, representing 25 denominations. So it’s no surprise that church records are abundant here. The largest collection is held at the Archives of the Diocese of Charleston (114 Rear Broad St., 843-724-8372, <www.catholic-doc.org/archives/archives.html>), established in 1820. Its holdings date from 1789 and include parish histories, property records, deed and construction files, some architectural drawings, cemetery records, newspapers and photos. Original registers containing sacramental records aren’t held in the archives, but it has microfilm of pre-1930 parish registers.

The easiest form of transportation in downtown Charleston is the Downtown Area Shuttle (DASH, 843-724-7420). You can purchase a ride-all-day ticket for $3 at the Charleston Visitor Reception and Transportation Center, also called the Visitors Center (375 Meeting St., 843-853-8000, <www.charelstoncvb.com>). Across the street is The Charleston Museum (360 Meeting St., 843-722-2996, <www.charlestonmuseum. org>), America’s oldest museum, founded in 1773. Exhibits focus on Colonial trade and commerce, the plantation system and more. The museum’s Discover Me Room has hands-on exhibits for children. Two historic homes are part of the museum: The Joseph Manigault House (350 Meeting St.), built in 1803, is a historic landmark that captures the lifestyle of a wealthy rice-planting family. The Heyward-Washington House (87 Church St.), built in 1772, was the home of Thomas Heyward Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Two other sites worth seeing downtown are Market Hall (188 Meeting St., 843-723-1541), a landmark built in 1841 that houses the Confederate Museum ‘s collection of flags, uniforms, swords and other Civil War memorabilia, and Old Powder Magazine (79 Cumberland St., 843-805-6730), which contains a bevy of artifacts from 18th-century Charleston.

Middleton Place

Where to Go, What to See…

During that century, more Revolutionary War battles were fought in South Carolina than in any other state. But Charleston is better known for its role in the Civil War, which began on April 12, 1861, at Fort Sumter. Later, from 1863 to 1865, the Confederates at Fort Sumter withstood a 22-month siege by Union forces. About 63,000 South Carolinians served in the Confederate army, and you can acknowledge their bravery at Fort Sumter National Monument (Charleston Harbor, <www.nps.gov/fosu>). Ferries to the fort depart from Municipal Marina on Lockwood Boulevard and from Patriot’s Point, located east of the Cooper River in the community of Mount Pleasant.

To enjoy some living history, travel 10 minutes northwest to Middleton Place (4300 Ashley River Road, 800-782-3608, <www.middletonplace.org>), a plantation built in 1741. It was the home of Henry Middleton, president of the First Continental Congress. In the stable yard, craftspeople use authentic tools and equipment to demonstrate spinning, blacksmithing and other domestic skills from the plantation era. The site, which plays host to “Plantation Days” on Saturdays in November, also is home to America’s oldest landscaped gardens.

Chefs in the Holy City can’t turn water into wine, but you should see what they can do with she-crab soup, sautéed shrimp and other Lowcountry cuisine. Try the crispy flounder at Anson (12 Anson St., 843-577-0551), a charming restaurant framed by about a dozen French windows. A contemporary, elegant choice is McCrady’s (2 Unity Alley, 843-577-0025), where locals go for tuna tartare. Magnolias (185 E. Bay St., 843-577-7771) is located in the city’s former customs house and specializes in Deep South dinners. Hominy Grill (207 Rut-ledge Ave., 843-937-0930) serves tasty, distinctly Southern dishes. If you’re in the mood for shellfish and oysters to go (or to sit — this place has six dining rooms), check out Hyman’s Seafood Co. Restaurant (215 Meeting St., 843-723-6000).

The city’s best-known hotel is upscale Charleston Place (205 Meeting St., 843-722-900, <www.charlestonplace.com>). It’s within walking distance of the South Carolina Historical Society, as is charming Mills House Hotel (115 Meeting St., 800-874-9600, <www.millshouse.com>) and Meeting Street Inn (173 Meeting St., 843-723-1882, <www.meetingstreetinn.com>). One block from the Battery (the southern point of Charleston, where the Cooper and Ashley rivers meet) is Hayne House (30 King St., 843-577-2633, <www.haynehouse.com>), built in 1755. Another good choice is the more moderate Anchorage Inn (26 Vendue Range, 800-421-2952, <www.anchoragencharleston.com>), built in the 1840s as a cotton warehouse.

– Darin Painter

Eco-tourism

Let the Old Times Roll New Orleans

Genealogy is more than just a hobby in New Orleans. For the people of this historic city, whom you come from determines who you are.

During the past three centuries, a person’s lineage could make him part of the city’s Creole elite, a Garden District American, one of the Gens de Couleur Libres (free people of color) or a slave. Today, the distinctions aren’t quite so dramatic. But the past lives on here, and the city’s lifelong residents still know whose families go way back — and whose don’t. Jan Voitier Dean was born and raised there, and says it’s the perfect place to get in touch with your roots: “I’ve had the pleasure of going into several of my ancestors’ nearly 200-year-old homes. What a thrill that was — I could practically feel my skirts swishing!”

New Orleans’ long history (the city was settled in 1718) and its reverence for genealogy will give you a leg up if you’re researching your Louisiana roots. If that’s your goal, a good place to start is the New Orleans Public Library (219 Loyola Ave., 504-529-READ, <nutrias.org>), which also serves as the city archives. “They have a vast collection of material that is tremendously useful,” says New Orleans professional genealogist Ellen Cleary <home.earthlink.net/????ellencleary>. “It includes an index to the obituary notices in New Orleans newspapers up to 1985; a biographical index; an index of Justice of the Peace marriages here; an index of birth, marriage and death records; and marriage and death certificates.” For a guide to the collections, visit <nutrias.org/????nopl/guides/genguide/ggcover.htm> or order a printed copy from the Friends of the New Orleans Public Library for $12.

Next stop: the Historic New Orleans Collection (533 Royal St., 504-523-4662, <www.hnoc.org>). Located in the heart of the historic French Quarter, this museum houses a noteworthy manuscript collection. “This is the place to do research on colonial Louisiana,” says Cleary. It also offers a survey of old New Orleans cemeteries that includes inscriptions and photographs of burial sites in St. Louis I and II, Lafayette I and II, St. Joseph I and II, Cypress Grove, Odd Fellows Rest and Greenwood cemeteries.

St. Louis Cathedral

Looking for early legal records? Try the Notarial Archives (421 Loyola Ave., 504-568-8577, <www.notarialarchives.org>), which contains all records of New Orleans notaries — important in the city’s French-inspired culture. “The Notarial Archives also has some wonderful information about the old houses here in New Orleans,” Cleary notes.

If you have African-American roots, don’t miss the Amistad Center at Tulane University (6823 St. Charles Ave., 504-865-5535, <www.tulane.edu/????amistad>). It specializes in African-American papers, as well as records of organizations and institutions in the African-American community. The center also has a smaller collection of holdings regarding Native Americans, Puerto Ricans, Chicanos, Asian-Americans, European immigrants and Appalachian whites. While you’re there, you might also be interested in the Louisiana Collection at the Tulane University Library (Jones Hall, 504-865-5685, <www.tulane.edu/????lmiller/LaCollection.html>). This is a research collection of printed materials relating to Louisiana history and culture, including the state’s best collection of 19th-century Louisiana books. In addition to 35,000 books and pamphlets, the collection contains maps, photographs, illustrations from popular 19th-century magazines, sheet music, newspapers and more.

While the many genealogical resources of New Orleans could make up your entire trip, the city’s historical attractions are just as enticing. Nearly every archive or library will have interesting places to see nearby. Stay at the Holiday Inn (330 Loyola Ave., 800-535-7830, <www.basshotels.com/holiday-inn?_franchisee=MSYDT>) across from the public library, and you can walk not only to your main research destination, but also to the French Quarter. Other convenient places to hang your hat are the Monteleone Hotel (214 Royal St., 800-535-9595, <www.hotelmonteleone.com>), the Olde Victorian Inn (914 Rampart St., 800-725-2446, <www.oldevictorianinn.com> and the Omni Royal Crescent (535 Gravier St., 800-843-6664, <www.omnihotels.com>).

A key attraction for history lovers is the Louisiana State Museum (751 Chartres, 504-568-6968, <Ism.crt.state.la.us>), a complex of national landmarks housing thousands of artifacts and works of art reflecting Louisiana’s legacy of historic events and cultural diversity. The museum operates five properties in the French Quarter: the Cabildo, the Presbytère, 1850 House, Madame John’s Legacy and the Old US Mint (which now houses the Louisiana Historical Center Library). Also take a tour of the Hermann-Grima House (820 St. Louis St., 504-525-5661, <www.gnofn.org/????hggh>), one of the largest and best-preserved examples of American architecture in the Quarter. And don’t forget about the “cities of the dead.” New Orleans’ cemeteries “are really worth seeing,” says Cleary. “Because New Orleans is below sea level, the dead are buried above the ground here. The inscriptions on burial sites often give you a capsule picture of the members of a family, when they were born and when they died.” Your best bet is a walking tour, since the cemeteries have a reputation for muggings. Try Magic Talking Tours (504-588-9693), led by local historians.

French Quarter

Food is a delicious part of New Orleans’ heritage, of course. And not just Gajun food, either — the city’s restaurants run the gamut from world-renowned gourmet (Commander’s Palace, 1403 Washington! Ave., 504-899-8221) to down-home country cookin’ (West End Café, 8536 Pontchartrain Blvd., 504-288-0711) on Lake! Pontchartrain. While you’re visiting the Louisiana State Museum or doing a bit of shopping around Jackson Square, pop in Café du Monde (Decatur and St. Ann streets,; 504-525-4544) for chicory cafe au lait and beignets heavily dusted with powdered sugar. For brunch, treat yourself to a traditional Creole meal at Brennan’s (417 Royal St., 504-525-9711), located in a gorgeous 19th-century building with a tropical courtyard.

– Susan Wenner Jackson

Where to Go, What to See…

Cafe du Monde

Golden Gate to Yesterday San Francisco

California’s “golden gate,” epitomized by the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, was more than merely metaphorical for the ancestors of millions of today’s Americans. For the forty-niners who came from the East seeking their fortune, California’s appeal was literally golden. For immigrants from Asia, California was the gateway to a new land.

Many of this latter group came through Angel Island, “the Ellis Island of the West” and the largest island in San Francisco Bay. A Miwok Indian fishing and hunting site for more than 6,000 years, the hilly island became an immigration station in 1910. But World War I cut short the flood of Europeans who were expected to arrive via the Panama Canal. Over the next 30 years, most Angel Island immigrants came instead from Asia — 175,000 from China alone. Because of restrictions on Asian immigration, the wait here was longer than at Ellis Island — an average of two to three weeks; some were detained for months or even years.

Today, the former immigration station on Angel Island is a National Historic Landmark. A museum in the old barracks building re-creates one of the detainee dormitories and preserves poems carved into the station’s walls by immigrants waiting for their chance at a new life.

The island is open from 8 a.m. to sunset year-round. Tours of historic sites are offered on weekends from April through October (call 412435-3522 for details), and you can take a motorized tram tour weekends in March and daily from April 7 through Oct. 31 (925-426-3058). Ferry service to the island is available from Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco ($10.50), Tiburon, Oakland/Alameda and Vallejo; links on the island’s Web site <www.angelisland.org> give fares and schedules. Or write the Angel Island Association, Box 866, Tiburon, CA 94920; for park-ranger information, call (415) 435-1915.

You’ll find the heritage of those Asian-Americans throughout San Francisco, but especially in Chinatown. There, the new Chinese American National Museum and Learning Center (965 Clay St., 415-391-118, <www.chsa.org>) and the Pacific Heritage Museum (608 Commercial St., 415-399-1124) celebrate the city’s Asian influences.

If your ancestors came from the other direction, lured by gold, you can get a feel for the Gold Rush at the Wells Fargo History Museum (420 Montgomery St., 415-396-2619, <www.wellsfargo.com/about/museum_info.jhtml>). Appropriately, it’s in the Financial District. The nearby Jackson Square Historical District is the best place to see buildings from the Gold Rush era.

San Francisco was built on seafaring as well as gold, and you can discover that heritage at the San Francisco Maritime Museum (at the foot of Polk Street, Fisherman’s Wharf, 415-561-7100). Besides models and exhibits inside, don’t miss the remarkable collection of actual ships on nearby Hyde Street Pier (415-561-7100). Stroll the deck of the three-masted schooner CA Thayer or the 2,560-ton ferryboat Eureka and you’ll appreciate what your ancestors went through to get anyplace by sea. This whole Fisherman’s Wharf area is rich in the heritage of the Italian immigrants who founded the city’s fishing industry in the late 19th century. (And if you had ancestors in prison, Alcatraz is just a short ferry ride from here, near Angel Island.)

Nearby Fort Mason (415-441-3400) reflects not only the city’s military history, but also its ethnic traditions: Almost 50 cultural groups make their home in Fort Mason Center (Marina Boulevard and Buchanan Street, 415-441-3400, <www.fortmason.org>), including the Mexican Museum (415-202-9700, <www.mexicanmuseum.org>) and Museo ItaloAmericano (415-673-2200, <www.museoitaloamericano.org>).

State history is honored at the California Historical Society (678 Mission St., 415-357-1848, <www.californiahistoricalsociety.org>). The society’s North Baker Research Library is open by appointment only.

Genealogists’ first stop should be the Sutro Library (480 Winston Drive, 415-731-4477, <www.library.ca.gov>), a branch of the California State Library Association. The library features the rare book and manuscript collection of Adolph Sutro and the largest genealogy collection west of Salt Lake City: 150,000 books and 65,000 microforms. It’s located between the north campus of San Francisco State University and the Stonestown Galleria mall. If you don’t have a car, take the Muni Metro train to the mall, walk through the mall and out the back and downhill to the left. The library is a low-slung building tucked into a hillside on the right-hand side of Winston Drive, a challenge for cab drivers to find.

San Francisco’s regular libraries also offer much for genealogists, such as the San Francisco History Room and Archives in the New Main Library (100 Larkin St., 415-557-4400, <sfpl.lib.ca.us>), in the Civic Center area. (If you stay in the nearby Union Square hotel area, don’t be tempted to stroll here through the iffy Tenderloin district.) While there, check out the exhibit of the Museum of the City of San Francisco <www.sfmuseum.org> in the neighboring City Hall South Light Court at Grove and Van Ness.

The Bay Area is also home to the National Archives and Records Administration’s Pacific Region headquarters (1000 Commodore Drive, 650-876-9001, <www.nara.gov/regional/sanfranc.html>), about 12 miles south in San Bruno, near the airport.

Across the bay in Oakland is the California Genealogical Society Library (1611 Telegraph Ave., Suite 100, 510-663-1358). It’s open to the public; there’s a $5 daily fee for nonmembers.

San Francisco’s multifaceted public transportation system makes it easy to get around. So your best bet for accommodations is probably a hotel in the Union Square area, which is convenient to the Muni Metro and to cable cars for Fisherman’s Wharf or Chinatown. (It’s also a shopper’s paradise.) The San Francisco Hilton (333 O’Farrell St., 415-771-1400) and San Francisco Marriott (55 Fourth St., 415-896-1600) are obvious big-hotel choices. Or opt for a bit of history at the classic Sir Francis Drake (450 Powell St., 415-392-7755) or the Westin St Francis (335 Powell St., 415-397-7000), built in 1904. An affordable alternative on the other side of Market Street from Union Square is the recently renovated Pickwick Hotel (85 Fifth St., 415-421-7500).

The problem with dining in San Francisco is the confusing variety of options in what’s one of the world’s great restaurant cities. For starters, you might try sampling some of the city’s heritage. For example: Italian at Puccini & Pinetti (129 Ellis St., 415-392-5500, <www.pucciniandpinetti.com>), seafood at Aqua (252 California St., 415-956-9662, <www.nextcenturyrestaurants.com/aquamain.htm>), Chinese dim sum at Yank Sing (101 Spear St., 415-957-9300, <www.yanksing.com>) and Japanese at Mifune (1737 Post St., 415-922-0337), in the striking Japan Center (Post and Buchanan streets, 415-922-6776) at the heart of the city’s Japanese community. *

– David A. Fryxell

From the November 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine