In July 1861, the first real battle of the Civil War was fought at Manassas, Va., near Bull Run Creek. Before the war and the 1858 arrival of the railroad, this area about 30 miles southeast of Washington, DC, was mostly farm country. Manassas wasn’t even formally chartered as a town until 1873, when war veterans from both sides began settling in the verdant land they’d seen under less-pleasant circumstances.

It was an entrepreneurial Union veteran, George Carr Round, who really established today’s town of Manassas, not far from where his side had suffered such a surprising defeat July 21, 1861, signaling that the Civil War would last longer than Americans had realized.

Today, you can find history not only at the historic battlefield, but also museums, Old Town Manassas, the Colonial-era town of Occoquan and Leesylvania State Park, birthplace of the father of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee.

There stands Jackson …

In the Battle of First Manassas (known in the North as First Bull Run), Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard commanded the main Confederate force of 22,000 men and Gen. Joseph E. Johnston brought most of a 10,000-man force from Richmond to his aid. But the Confederate general most associated with both battles of Manassas was Thomas J. Jackson, who earned his famous nickname of “Stonewall” at First Manassas.

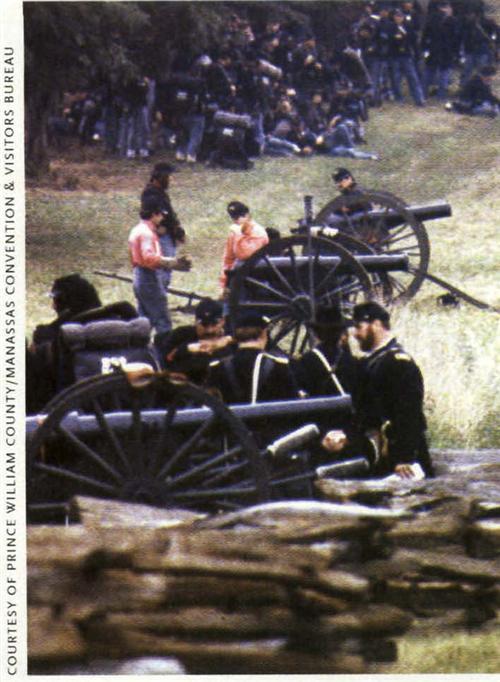

A statue of Stonewall Jackson astride his horse, Little Sorrel, towers over today’s Manassas National Battlefield Park. The Stone House, a Union field hospital during the battle, still overlooks the Warrenton Turnpike as it has since the 1820s. A reconstructed farmhouse marks where the Henry House stood in 1861, near the nexus of the struggle over these 500-some rolling acres. Visitors can pause at the grave of Judith Carter Henry, the only civilian killed in the first battle. Every July and August, re-enactors camp on the park grounds and bring to life the two battles that made Manassas famous.

Begin your tour at the visitor center, a short walk from the Henry House and just off Highway 234 (exit 47 off Interstate 66 or south from US 29). The center’s museum will orient you to the battlefield before you troop out there in person.

The First Manassas battlefield is easily walkable; you can follow a one-hour, self-guided tour that takes you over the ground where Union Gen. Irvin McDowell sent his raw recruits, 35,000 strong, against the Confederates. When that thin gray line began to give way, Confederate Gen. Barnard Bee sought to rally his troops by pointing to the newly arrived brigade led by Jackson: “There stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!” Rally they did, holding their ragged positions until late in the afternoon.

Then, fresh Confederate troops arrived to strike the Union’s right flank on nearby Chinn Ridge, and McDowell’s men began a withdrawal that devolved into a chaotic rout. The fleeing Northern soldiers collided with the carriages of congressmen and others who’d driven to nearby Centreville to enjoy the spectacle of certain Union victory, and Americans got their first taste of the brutal realities of the four years that lay ahead.

The two sides met again at Manassas in August 1862. This more sprawling battle requires a 16-mile driving tour, covering 11 key sites, to revisit. You’ll see where the Union forces under Gen. John Pope clashed with the armies of Jackson, Gen. James Longstreet and Lee. Over three days, 3,300 soldiers perished, and again the immovable Jackson helped win the day for the South. Lee’s victory at Second Manassas opened the way for his bold invasion of the North, which ended at Gettysburg.

Out of the ashes

Fifty years after First Manassas, in 1911, surviving veterans from both sides returned for an anniversary National Jubilee of Peace, billed as the “Love Feast of the Blues and the Grays.” You can see photos and artifacts from that day at the Manassas Museum, which chronicles the whole history of the area, from prehistoric tools to Victorian costumes to quilts.

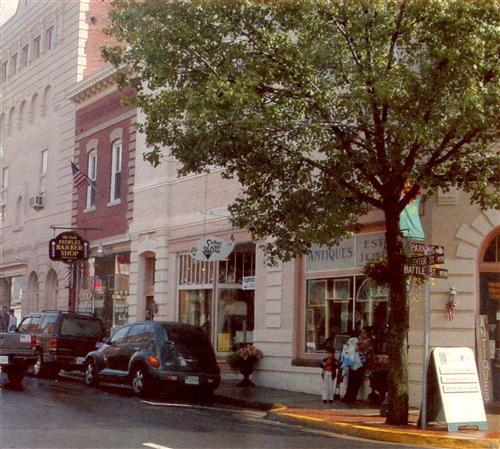

You’ll also learn about the 1905 fire, possibly caused by sparks from the railroad, that claimed 57 buildings and caused most of Manassas to be rebuilt — almost entirely in brick, with fire-resistant tin roofs. The happy result of that fiery accident is a charming, Edwardian-era town that looks very much as it did in the years before World War I.

To explore Old Town Manassas, cross Prince William Street from the museum and begin at the train depot, which now does added duty as a visitor center and the Railroad Heritage Gallery. If you’re visiting Washington, DC, you can take Amtrak straight to the depot and a day trip to Old Town.

Across the tracks, dozens of specialty shops, galleries and eateries entice you. History buffs will want to spend time at Prospero’s Books, which specializes in out-of-print books and antique maps and prints. Don’t miss the town’s many historic churches — in the 1930s, the Guinness Book of World Records said Manassas held the record for most churches per capita.

A few blocks north and east of your window-shopping is the 1890s Old Manassas Courthouse, a rare survivor of the town fire. This Romanesque Revival gem, appropriately located at the corner of Lee and Grant avenues, was the site of the 1911 Jubilee.

If all this history gives you an itch to take some home with you, one of the region’s leading antiques auction houses, Bull Run Auction Inc., is just up the road. Bone up on your bidding skills before you go. It’s on Highway 28 south of US 29, also known as the Lee Highway.

A Lee legacy

It’s not just the road names that make you think the spirit of Robert E. Lee is everywhere in northern Virginia. Though the great general’s birthplace lies farther south at Stratford Hall, Lee’s father was born in eastern Prince William County, where Occoquan Bay juts out of the Potomac River. That father was pretty well-known in his own day, as “Light Horse Harry” Lee, dashing cavalry colonel to Gen. George Washington and governor of Virginia. “Light Horse Harry” Lee’s birthplace is today part of Leesylvania State Park in Woodbridge.

This lovely area has been drawing visitors since long before the Lee family, beginning with American Indians some 8,000 years ago. Capt. John Smith and 26 of his men took a barge here from Jamestown in the early 1600s. In 1747, Henry Lee II, grandfather of Robert E. Lee, inherited the land and began building a plantation he dubbed Leesylvania, meaning Lee’s woods.

In 1753, he brought his new wife, Lucy Grymes, to Leesylvania, where they had eight children. Only the barest outline of the Lee plantation can be seen in the woods today, though the Lee family gardens “escaped” long ago and continue to fill the park with spring blossoms. Henry Lee II and Lucy are buried here, but the exact spot is unknown; a bronze plaque from the Society of the Lees of Virginia honors their memory.

Seven years after Harry died in Georgia in 1818, the Fairfax family (as in Fairfax County, Va.) bought Leesylvania; the chimney and other ruins of their original house, as well as the Fairfax family graveyard, can be seen along a brisk nature hike.

But the Lees weren’t quite done with Leesylvania. During the Civil War, Robert E. Lee ordered earthworks built on his old family property to help blockade the Potomac River. The artillery battery there was involved in a brief naval battle Sept. 25, 1861. You can still see the Civil War earthworks and enjoy the same lovely view of the river that their gunners saw.

After the war, in 1872, the railroad cut a swath through the area and destroyed most of the historic structures, and Leesylvania became overgrown and forgotten. A multimillion-dollar renovation begun in the 1980s turned Leesylvania into a state park in 1992.

Ghosts and George Washington

The stretch of Prince William County that hugs the broad Potomac was settled first and so has an older history, reaching back to Revolutionary and Colonial times. Just across Occoquan Bay from Leesylvania, for example, the town of Occoquan has been a shipping port since 1734. (The name comes from a Dogue Indian word for “at the end of the water.”) The nation’s first fully automated gristmill was built here in 1759. Fire later destroyed the mill (and much of the town), but the miller’s office survives as the Mill House Museum.

After the Route 1 highway opened in 1928 and the Occoquan River silted in, the town became trapped in a charming time warp. Many of its 100- and even 200-year-old buildings are now occupied by specialty shops, antiques stores and galleries. Every spring and fall, downtown fills up with artists and craftspeople in the large Occuquan Arts & Crafts Show.

When you want a break from browsing, stop in at the Virginia Grill, in the former Occoquan Inn, built in 1810. Or, down the street, enjoy riverfront dining at Sea Sea & Co. (201 Mill St.).

You can explore early Virginia history just a few miles to the south at the Weems-Botts Museum in Dumfries. The house was bought in 1798 by Mason Locke Weems, better known as “Parson Weems”—author of The Life of Washington and inventor of the famous tale of George Washington and the cherry tree. Weems used the house as his writing office and bookstore. The house, restored in 1975, still has its original floor and ceiling, and is decorated in period furniture.

Making military history

Modern-day military history is here, too, at the Quantico US Marine Corps Base and the National Museum of the Marine Corps and Heritage Center. It features an IMAX theater and 120,000 square feet of exhibits tracing the history of the Marine Corps, topped by a 210-foot tilted mast and glass atrium inspired by the flag raising at Iwo Jima.

Prince William County’s pivotal location—on the Potomac, near the capital, between Washington, DC, and the one-time Confederate capital of Richmond—has made it a crossroads for much of American history.

But it’s not just the grand sweep of history that strikes you here. You can stand on the green knolls of the Manassas battlefield, for instance, and eye the shockingly narrow distance that separated Blue from Gray. Suddenly, the scale of the struggle becomes humanized: Could you have faced the enemy at such close range and stood like a stone wall? What must it have been like to see the surge of soldiers, surely just as terrified as you might be, coming out of the shimmering summer day? Listen hard enough, in the foggy quiet of yesterday’s battlefield, and you can almost hear the cannons echo.

Getting there

Manassas, Va., is about an hour’s drive on I-66 from Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. The Woodbridge and Occoquan areas are about 20 miles south of the airport on Interstate 95. Hotels are mostly clustered along the two Interstate corridors. For visitor information, see the Prince William County/Manassas Convention & Visitors Bureau.

Adapted from the Summer 2003 Heritage Travel.