Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, the Spanish conquistador who explored Arizona in 1540, never found the fabled seven cities of gold. But your quest for family tree treasures in Arizona can prove much more successful once you know where to look. Although Arizona was the last of the contiguous United States to join the union-pinning the 48th star on the flag in 1912—it offers a wealth of resource riches stretching back to its earliest territorial days. Besides a well-stocked state archives, Arizona boasts perhaps the country’s best vital-records Web site <genealogy.az.gov>:Here you can search for birth certificates (1887 to 1929) and death certificates (1878 to 1954), then view the record images as PDF files. No wonder the site’s logged more than 3 million hits since its launch in January 2004.

Ancient history

Of course, Coronado wasn’t first to set foot in the future Grand Canyon State: Zuni, Hohokam, Anasazi, Mogollon, Apache, Navajo, Hopi and other Indians had lived there for 12,000 years. The Hopi village Old Oraibi is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the United States. Today, 21 federally recognized Arizona Indian tribe-including the country’s largest tribe, the Navajo-live on 22 reservations. See the April 2004 Family Tree Magazine for help researching Indian roots. Also check the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> for microfilmed Bureau of Indian Affairs records from several Arizona agencies. (See <www.interior.gov/leaders.pdf> for an agency list.) Originals are at the National Archives and Records Administration Pacific Region facility in Laguna Niguel, Calif. (949-360-2641, <archives.gov/pacific/laguna>).

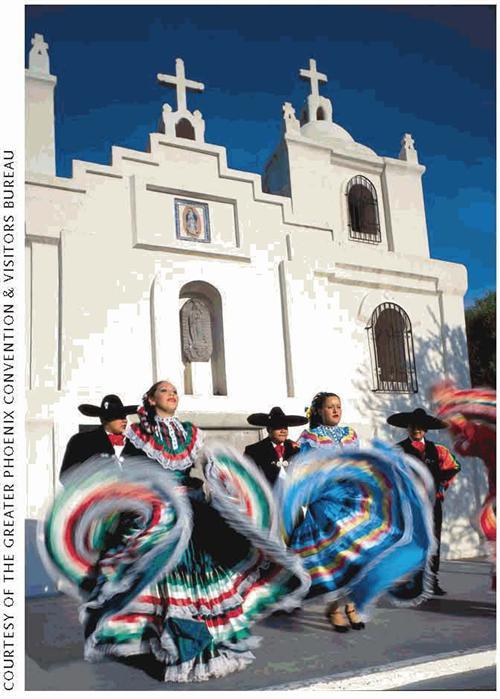

When Coronado came through, the Zuni steered him northwest. For more than two centuries thereafter, the Spanish seemed almost to forget about Arizona, which was colonized more slowly than neighboring New Mexico. They returned to found Tubac in 1752 and Tucson in 1775. Thanks in part to Apache raids, settlement still clung to the southern area of the state in 1821, when newly independent Mexico made Arizona part of the state of Sonora.

If you’re researching early Hispanic ancestors, several published indexes cover Mexican censuses for the area that’s now Arizona, including 1831 for Tucson, Tubac and Santa Cruz, and 1801 and 1852 for Pimeria Alta. You can find these early documents at the state archives in Phoenix and at the Arizona Historical Society in Tucson (see resources). Other records may be in repositories in New Mexico or even Mexico. You also can dig into Spanish and Mexican land grants, of which the New Mexico archives has some early records. For guidance, consult Spanish and Mexican Land Grants in New Mexico and Colorado edited by John R. and Christine M. Van Ness (Sunflower University Press, out of print).

Wild, wild West

In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War and Mexican rule for Arizona north of the Gila River. Arizona was initially part of New Mexico Territory—you may need to look in New Mexico when using early territorial records, such as the 1860 US census. The Gadsden Purchase of 1853 added the rest of present-day Arizona to the country.

To maintain control and protect settlers from Indian tribes, the US government established forts, where soldiers and their families lived. See a partial list and resources at <jeff.scott.tripod.com/forts.html>. Some encampments, such as Fort Verde (see historic sites) have museums and visitor centers. Arizona Territory split off in 1863, beginning almost 50 years of colorful pre-statehood history that included the 1881 shootout at the OK Corral in Tombstone.

The new territory organized four counties — Yavapai, Mohave, Yuma (previously called Castle Dome) and Pima — in 1864. Two years later, the northwestern part of Arizona Territory, Pah-Ute County, was transferred to the newly minted state of Nevada. Today, Daniela Moneta, genealogy librarian for Arizona’s state archives <www.1ib.az.us/archives>, cautions that although Arizona’s a large state, it has only 15 counties. Travel from one county cow-house or historical society to the next is time-consuming, so plan accordingly.

The government took territorial censuses of Arizona in 1864, 1866, 1867, 1869, 1871, 1872 and 1882. They’re available at the state archives, though not all are complete. The FHL has indexes for 1864, 1866, 1867 and 1869. (You can rent microfilm for viewing at an FHL branch Family History Center-find one using the box on the FamilySearch home page.)

Arizona Territory became part of the federal census starting in 1870. This head count, along with censuses for 1880, 1900 and 1910, is available on FHL microfilm and in the subscription census collections at Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > ($99.95 per year) and Genealogy.com<www.genealogy.com> ($99.99 per year). You can access them free through libraries that subscribe to HeritageQuest Online <www.heritagequestonline.com>. Supplement census records with Great Registers of voters, which cover various counties and years from 1882 to 1911-they’re at the state archives.

Between 1870 and 1910, Arizona’s non-American Indian population ballooned from less than 10,000 to 200,000-plus. If your ancestors arrived during this territorial period, you can apply for a pioneer certificate application — see <www.azgab.org/pioneer-certificate.htm> for details. Early ranchers may have registered their marks in cattle-brand books, available at the state archives. Statehood came at last in 1912, and the 1920 US census was Arizona’s first as a state.

Sunny outlook

The post-WWII boom years further shaped Arizona as Americans flocked to the sun. Phoenix’s population grew from 100,000 to 980,000 between 1950 and 1990. In 1960, the Del Webb Corp. gave rise to the idea of Arizona as a retirement haven with the creation of Sun City.

The state archives is the best place to begin your research, advises Barbara B. Sayler, a professional genealogist and Arizona State Genealogical Society (ASGS)<www.rootsweb.com/~asgs> past president. The collection includes records of marriage, civil and criminal cases, probates, insanity commitments, inquests, wills, estates and naturalizations, as well as deeds, censuses, assessor rolls and the Great Registers of voters.

Next door in the Law and Research Library, you’ll find obituary and cemetery indexes, city directories, school yearbooks, maps and a large genealogy collection. See <www.lib.az.us/is/genealogy> or search the online catalog via the link on that page. You can search or browse the archives’ 100,000-entry biographical database without leaving home at <www.lib.az.us/bio>.

Prior to 1909, when statewide birth and death registration began, counties kept vital records. Participating counties sent copies to the Arizona Department of Health Services; this provided the source for the records now available online. The Office of Vital Records (see resources) also has some delayed birth (from 1855) and death (from 1877) certificates containing information from other sources. The clerk of the superior court in the county where a birth or death occurred kept the originals. Arizona has no statewide marriage registration: A law passed in 1864 required county recorders to keep marriage and divorce records. From 1891 to 1912, clerks of probate courts issued marriage licenses. Look for marriage records, as well as those of probates and divorces, in the superior court for your ancestor’s county.

State law shields birth records for 75 years and death records for 50 years from everyone except family members with proof of relationship. (Legislation pending at press time would increase the privacy period for birth records to 100 years.) Obituaries and cemetery records help fill in blanks when you can’t find a death certificate. The ASGS’ collection of death records from cemeteries, mortuaries and churches is at the state archives, as is microfiche drawn from an 1865-to-1986 obituaries index. Local genealogical societies have published a slew of cemetery and other records-check the FHL’s online catalog (do a place search on the county name) or see the list at <www.azgab.org/project_registry.htm>.

The Grand Canyon State has a rich tradition of journalism, beginning in 1859 with the Weekly Arizonian in Tubac. Since the state library was established in 1864, it has retained all known Arizona newspapers. Out-of-print and microfilmed papers move to the archives. For more information, see <www.lib.az.us/is/newspapers.cfm> and explore the Arizona Newspaper Project at <www.lib.az.us/anp>.

Sayler also recommends checking the collections at Arizona’s university libraries (see resources). In particular, don’t miss the thousands of photographs, diaries, letters, oral histories and maps in Northern Arizona University’s Colorado Plateau Digital Archives <www.nau.edu/library/speccoll>. Even if, like Coronado, you end your travels with empty pockets, at least research in Arizona will leave you with a full pedigree chart.

From the April 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.