Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The first step in tracing your Georgia ancestors might be to shake your preconceptions of this state, which presents many different faces to history: Georgia was the last of the original 13 colonies, a frontier where settlers pushed Indian tribes out of the way, as well as the jumping-off point to the Old Southwest of Alabama, Mississippi and beyond. It was the core of the Confederacy, yet today it epitomizes the “New South.” Whichever face of Georgia your family saw, your genealogical research efforts are sure to bear fruit.

A slice of early history

Georgia started as a buffer between British and Spanish colonial ambitions. The British chartered a Georgia province in 1732; the next year, James Oglethorpe and 35 families founded Savannah. Oglethorpe had promoted the colony to British debtors threatened with imprisonment, but few actually settled there. Instead, the colony became a haven for poor English and Scottish tradesmen, as well as Protestant and Jewish refugees from Switzerland, Germany and Italy.

After slavery was legalized in 1751 and Georgia became a royal colony in 1752, settlers from Virginia and the Carolinas began to drive population growth there. That triggered the dizzying divvying up of Georgia into a patchwork of counties: The two original counties formed in 1740 became 12 parishes between 1758 and 1777, when they merged into seven counties. Almost all the surviving pre-1777 vital, land, court and other public records are in the Georgia Archives <www.georgiaarchives.org>. The archives Web site has a name index linked to images of Colonial-era will books (1754 to 1779) and wills (1733 to 1778); click What do We Have? then Online Records.

Statehood blossoms

Ten years after achieving statehood in 1788, Georgia’s western portion split off into the Territory of Mississippi (today’s Alabama and Mississippi). Since then, the state’s been further divided into today’s crazy quilt of 159 counties (many with names similar to towns located in other counties — the city of Macon, for example, isn’t in Macon County). Georgia GenWeb’s county list <rootsweb.com/~gagenweb/countyList.htm> is a good starting point for unscrambling the patchwork.

Revolutionary War soldiers from Virginia and the Carolinas who had fought in Georgia fueled the state’s postwar growth. Land lotteries in 1805, 1807, 1820, 1821, 1827, 1832 and 1833 doled out chunks of newly opened territory. The state archives has original records of the lotteries (search an online index at <www.georgiaarchives.org/what_do_we_have/online_indexes>), but these and other early land and tax records are available on Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> microfilm (rent it through a branch Family History Center — use the FamilySearch site to find one). Many of the records also are in Ancestry.com’s <Ancestry.com > subscription databases ($155.40 per year). Look for Early Georgia Settlers, 1700s-1800s, a compilation of six books detailing 18th- and early 19th-century Georgia records, which is searchable in Genealogy.com’s <genealogy.com> Genealogy Library (part of the $69.99-per-year basic membership) and available on CD (see resources).

The pressure on American Indian lands intensified with the 1828 discovery of gold near Dahlonega, culminating in the 1838 forced removal of thousands of Cherokee to Oklahoma. An estimated 4,000 Indians died along the Trail of Tears. Records of early tribes, including the 1832 Creek and 1835 Cherokee censuses, are available from the FHL.

Ripe for conflict

With the growth of “King Cotton,” the mainstay of Georgia’s economy, came an explosion of slavery. By the start of the Civil War, slaves made up 44 percent of Georgia’s population. The FHL has a number of resources for researching African-Americans in Georgia, including microfilmed records of the state’s three branches of Freed-men’s Bureau banks.

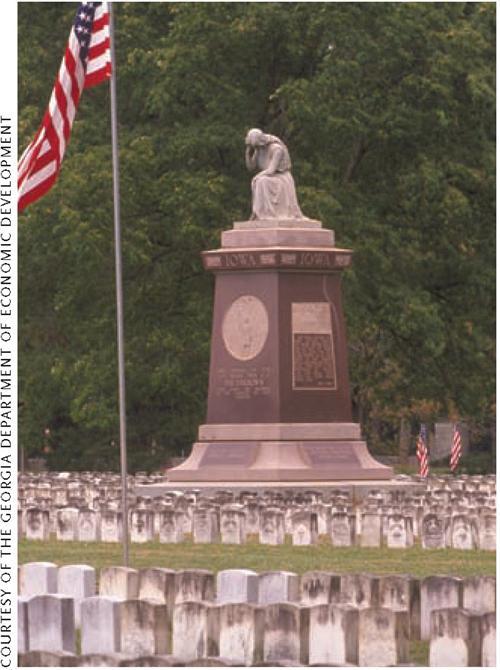

Secession in 1861 and the ensuing Civil War mark a sharp break in Georgia’s history. More than 100,000 Georgians fought for the Confederacy. The burning of Atlanta (so vividly re-created on film in Gone With the Wind) and Sherman’s march to the sea spelled the beginning of the end for the South’s hopes of victory. Contrary to legend, Sherman’s troops burned few courthouses, although nearly a third of Georgia’s counties have lost records to fire, storms and other causes.

The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System <www.itd.nps.gov/cwss>, an index to 6.3 million Union and Confederate soldier names, is a good starting point for Civil War ancestors. You can research Confederate soldiers on the Georgia Archives’ 500 rolls of microfilmed pension records, arranged by county, then surname. Some pensions are digitized on the archives’ Web site, along with Confederate muster rolls and oaths and discharges. The FHL has pensions and other Civil War records on microfilm; run a place search of the online catalog on georgia and look under Military — Civil War. For more Civil War research advice, see the October 2005 Family Tree Magazine.

Fruitful resources

When you’re ready to pursue Georgia ancestors in person, you’ll enjoy visiting one of the nation’s newest state archives buildings, dedicated in 2003 (and conveniently located next-door to the new National Archives and Records Administration’s Southeast Region <archives.gov/southeast>). The Georgia Archives has government records, tax digests, private papers, church and cemetery records, newspapers, family Bibles, land grants and maps. Don’t miss the General Name File Cards, an index to mostly pre-Civil War military records that started as a WPA project. Another important repository is the Middle Georgia Archives <www.co.bibb.ga.us/library/mgarchives.htm> in Macon, notable for its family and business papers, club and organization records, and photos.

Can’t make the trip? Visit the Virtual Vault <www.sos.state.ga.us/archives/vault/arcvirtualvault> of plat and other maps and documents, and the Vanishing Georgia <dlg.galileo.usg.edu/vanga.html> collection of 18,000 photos. Check out these records, too:

• Censuses: Tax and property records often can substitute for the 1790, 1800 and 1810 US censuses of Georgia, all of which are lost (except Oglethorpe County’s 1800 count). The Reconstructed 1790 Census of Georgia by Marie De Lamar and Elisabeth Roth-stein (Genealogical Publishing Co., $28.50), included in Early Georgia Settlers, enumerates 15,000 Georgians using wills, deeds, tax digests and other resources. Let records of the 1805 land lottery stand in for the 1800 census — entrants had to be in the state by 1802 to qualify. Federal census records begin with 1820 (except for Franklin, Rabun and Twiggs counties, which start later).

The state took censuses of various counties between 1798 and about 1879; many are on FHL microfilm — to find them, run a place search of the online catalog on a county name.

• Vital records: Although counties kept marriage records starting in 1804, Georgia didn’t attempt statewide vital registration until almost the end of Reconstruction, in 1875. That experiment lasted only a year, and the state didn’t require recording of births and deaths again until 1919. Even then, it was 1928 before most counties complied. Worse yet, Georgia has some of the toughest laws restricting birth certificates: Access is limited to the person named or his parents, legal guardian, grandparents, spouse, sibling or child. Anyone can get death certificates, either from the state vital-records office or individual counties. The state has marriage records only from 1952 on; earlier ones are at the county probate courts that issued the licenses. Only a handful of vital records are on FHL microfilm.

For pre-1919 births, you may be able to find a delayed birth certificate — a citizen born before birth recording could apply for one of these to become eligible for employment benefits. Held at the state vital-records office, delayed certificates often include the documents applicants had to provide.

• Newspapers: Georgia has some of the most complete newspaper archives in the nation, ranging as far back as 1763. The state’s oldest newspaper, the Augusta Chronicle, has a searchable online archive <www.augustaarchives.com> of digitized papers spanning almost 200 years; a one-day pass costs just $4.95. Ancestry.com offers the digitized, searchable Atlanta Constitution dating from 1868, with some gaps. The Georgia Newspaper Project <www.libs.uga.edu/gnp> has microfilmed more than 2,500 titles. You’ll find a handful online in the Digital Library of Georgia < dlg.galileo.usg.edu>, which connects you with 500,000 images and text pages from 135 organizations. With all these resources, you’ll have a peachy keen time researching your Georgia roots.

From the December 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.