In 1953, newlyweds Frank and Drema Riser shared a home with Frank’s parents in a small West Virginia coal town. His father and brothers had been miners, and Frank was expected to join them underground. Instead, he followed his brother-in-law to Cleveland, where he immediately found work at a General Motors auto plant. Drema soon joined him, and they raised their family in Northern Ohio.

Their experience was more typical than they knew: More than a million people fled the overworked hills of Appalachia for Midwestern factory jobs in the two decades after World War II. But the story of Appalachian families as we know them, the “mountain people,” began long before, when their ancestors migrated into the stunning highlands and lush valleys of the oldest mountains in North America.

The history of Appalachia is a mountain of stories: Tales of Cherokees who slipped silently into the woods to avoid the often-fatal Trail of Tears. Revolutionary War veterans who homesteaded steep hillsides. Recently emancipated African-Americans who labored on mountaintop logging crews. European immigrants who descended into pitch-black coal mines to provide for their families. And, of course, folks like the Risers, who left their hills and families behind but keep them in their hearts to this day.

Sit a spell, and we’ll tell you their stories. You’ll learn about mountain life and discover three local sources essential to finding your Appalachian kin.

The Settlers of Appalachia

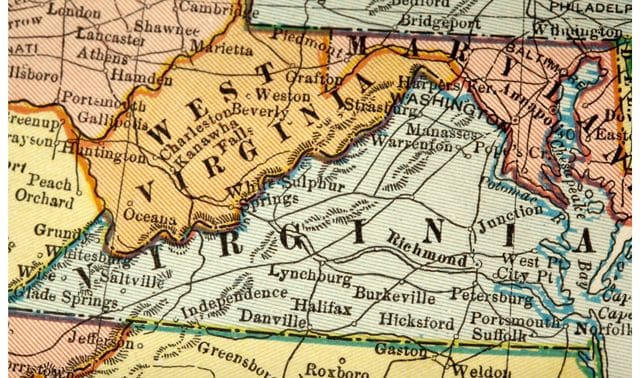

Technically, Appalachia describes the inland spine of the eastern US, where the mountain range stretches from New Hampshire to Alabama. Cultural Appalachia includes all of West Virginia and parts of 12 surrounding states (see map on next page). It’s a place of misty mountains that John Denver called “almost heaven” and green valleys serenaded in the folk song: “Oh Shenandoah, I long to see you and hear your rolling river.” It’s a place where mountain people have eked out lives in the forested ridges and “hollers” for generations.

In the early 1700s, the would-be “first” settlers found the Appalachian highlands already laced with towns and trails of thousands of native peoples. The Cherokee were the predominant tribe in the Carolinas; Chickasaw, Chocktaw, Shawnee, Creek and others surrounded the region. Over the next century, encroaching settlers gradually displaced native dwellers, often violently. A few Native Americans melted invisibly back into the hills. Many were quietly absorbed into the new population.

The majority of early Appalachian settlers were English or Scots-Irish. The English came as immigrants from northern England or colonists from neighboring regions. Scots-Irish immigrants formed tiny communities in the “backcountry” as early as 1718, after finding no welcome in major colonial ports. Some claim that Scots-Irish independence, resourcefulness, and emphasis on faith and family are the foundation of Appalachian cultural values.

Several roads cut across Appalachia before the Revolutionary War, though settlement remained sparse until after it. The Great Wagon Road led from Philadelphia to Georgia, veering off at several points on roads called by other names. The Valley Pike led from the Shenandoah Valley to Roanoke, Va.; the Carolina Road from Roanoke to cheap land in the Carolina Piedmont. The Wilderness Road, built in the 1770s, opened Kentucky and points west. The latter route proved so popular it was eventually replaced by a national turnpike: the Cumberland Road.

By 1790, about 80,000 people called the Appalachian region home. Most of the area remained unsettled and politically undefined. But as the young nation expanded at the seams, immigrants and adventurers pushed further into the highlands. Thousands of Scots-Irish, Germans and others who had settled central Pennsylvania gradually descended southwest. The region’s population nearly doubled to 150,000 within 10 years. Tillable valley land was claimed first; later arrivals edged up the rugged mountain ridges.

Folks continued to move around and through Appalachia during the antebellum era. An 1830 gold rush brought thousands into Georgia’s Cherokee territory. Land-hungry settlers drove Cherokee and others from the highlands from the 1830s (most famously on the Trail of Tears in 1838). Carolinians and Virginians migrated south and west in the 1830s through 1850s to Georgia, Alabama and Arkansas after repeated crop failures and financial depression. Some settlers stayed only briefly, moving westward as new frontiers opened.

During the Civil War, Appalachia became a battleground. Not many slaveholders lived in the region (about 10 percent of the population was African-American at the war’s outset), but of the 100,000 soldiers from Appalachia, a solid majority fought for the South. The Shenandoah Valley and Gettysburg saw the most bloodshed, but guerrilla bands from both sides raided farms and small towns throughout the region.

The war introduced outsiders to Appalachia’s untapped natural wealth. Corporations soon began stripping the mountains on a massive scale, first of timber and then of coal. Laborers poured into the region: The population of the central Appalachian plateau increased sixfold in 40 years, from less than 200,000 in 1880 to more than 1.2 million in 1920. Many newcomers were newly emancipated African-Americans, and large numbers of poor immigrants were recruited into mining and logging fresh off the boats. By 1910, more than 5,000 coal mines in central Appalachia employed a half-million men and boys.

In the early 1900s, well-paying factory jobs began luring Appalachian families to the Midwest. Those who stayed felt the effects of the Great Depression, though old-timers joke they were already so poor they didn’t notice. Miners unionized in 1935, which improved working conditions, and work remained steady in Appalachia through World War II. The Tennessee Valley Authority, founded in 1933, brought electricity and jobs to rural Tennessee and parts of surrounding states, but also displaced thousands of families with dam projects.

In the two decades after World War II, decreasing demand for coal meant fewer workers were needed. The “Great Migration” followed: More than a million mountain folk like the Risers left home for blue-collar work in the Midwest.

That’s not to say Appalachia lost its charm. Children of those migrants (including the Risers’) recall regular weekend trips back into the hollers to visit kinfolk. A 1960s “back to the land” ethic sparked new respect for the hard-working, simple-living ways of Appalachians. Historians and social scientists began capturing their stories in earnest.

The Appalachian Regional Commission, founded in 1965, set official borders for the region and started pushing for economic development in the 13 states. Since 1970, new immigrants from India, Iran, Japan and Spanish-speaking countries have layered their stories on top of those who lived there before.

Finding Appalachian Family History Records

Researching your Appalachian roots is not unlike vacationing there. Large data sets and record collections are like large Appalachian cities: uncommon but, when you find one, uncommonly wonderful. Little local sources are worth the effort it takes to find them. The often-slow pace makes you appreciate the journey and the folks you meet by the wayside.

“It’s really hard to track people [in Appalachia],” admits Dean Williams, a manager in the Special Collections Library at Appalachia State University. “It can take a lot of digging to find them. County records are valuable, but they’re not indexed well. [Local] newspapers go way back, but there’s absolutely no indexing. You may find yourself sitting down and going through reels of microfilm. (It’s still worth checking websites with digitized newspaper collections first — for example, pay site GenealogyBank has some coverage of the region.)

On the upside, Williams says, “There are a lot of very localized sources, if you can get into them.” He describes church minutes, ledger books from general stores, even “Uncle Jake Carpenter’s Anthology of Death,” one man’s record of local births and deaths. “You’ve got to double-query some of the local sources, but you’ve got a good chance at finding someone.”

Start your Appalachian research with the usual records, Williams says: home sources, census records and county records such as wills and deeds, when available. Although you won’t find categories of uniquely Appalachian resources, similar to town records in New England or plantation records in the South, three often-overlooked source types have special application to Appalachia: Be sure to investigate bounty land grants, ethnic records and oral history collections.

Genealogical Bounty: Finding Bounty-Land Records

Appalachian settlers included veterans who received a chunk of the frontier in exchange for military service. Federal and state governments paid soldiers this way from Colonial times through the time of the Mexican War (1846 to 1848). Land awarded in Appalachia was most frequently paid out by individual states, not the feds, and most (but not all) of it was for Revolutionary War service.

As early as 1646, Virginia granted land surrounding frontier forts to the military men defending them. The colony also awarded bounty land for service in the French and Indian War, though the land wasn’t freed for settlement until after the Revolution. (A young George Washington, who served the Virginia Regiment, chose several riverfront tracts in what’s now West Virginia.)

After the Revolution, Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia all awarded bounty land outside their modern boundaries before eventually ceding claims to that land to the federal government. Virginia assigned acreage in Kentucky and Ohio; North Carolina gave away parts of Tennessee until 1800. Georgia, New York, Pennsylvania and South Carolina awarded plots within their own boundaries, some until the mid-1800s. West Virginia wasn’t a state until after the Civil War, so it didn’t grant bounty lands.

Bounty-land paperwork includes various types of documents and data. Bounties weren’t automatically awarded, but original applications (even rejected ones) were in many cases kept by states. If an application was successful, a warrant was issued in an amount determined by rank and length of service. (Note: Warrants issued at the federal level are also kept there.) Warrants that were redeemed became part of bounty files, as did related paperwork, such as a letter reassigning the warrant to an heir. In these documents, you’ll find the soldier’s vital statistics, military service details and information on any heirs, including widows. Many are available on microfilm or on subscription site Ancestry.com.

The individual states that assigned bounty lands retained the resulting records. Many are available through state repositories, some even online. For example, the Kentucky Land Office offers searchable access to images of nearly 5,000 Revolutionary War warrants. At the Library of Virginia, you can search both Revolutionary War warrants and rejected applications. Check with individual state archives for original records. Consult an 80,000-record index to Revolutionary War pension and bounty land applications at HeritageQuest Online, free to patrons of subscribing librarians. You can also check Revolutionary War Bounty Land Grants by Lloyd deWitt Bockstruck (Genealogical Publishing Co.), a 35,000-name master index to state bounty land records that’s searchable on Ancestry.com.

The Heritage of Appalachians: A Mountain Melting Pot

“People tend to think of people in Appalachia as white — Scots-Irish — but it was a real mix,” Williams says. “There was a large German presence in [Boone, NC] in the late 1800s. [Companies] also brought in large numbers of Italians and Poles and people from Central Europe. They needed people with experience in deep mines. There was a Hungarian colony in north Georgia. In pockets, there were sizable black populations. And of course there were Native Americans.”

Appalachia wasn’t quite a happy melting pot. Ethnic groups that arrived together tended to stay together. Segregated neighborhoods formed near mines, populated by Greeks, Czechs, Yugoslavians, Austrians, Italians, Welsh or Russians. Isolated in the highlands and valleys, these tiny groups attended their own churches when possible and were even buried separately. The upside of segregation is that ethnic identities remained strong: You may have luck tracking your forebears (or their communities) through ethnic sources.

Original records relating to ethnicity in Appalachia are most frequently found in the form of church records. Before the early 1800s, if your ancestors were Scots-Irish, look for Presbyterian records, and for Germans, look for Lutheran, Catholic or Jewish records. Eventually, Baptist and Methodist sects drew Appalachians of many ethnicities; learn which faith your ancestor may have followed in Appalachian Mountain Religion: A History by Deborah Vansau McCauley (University of Illinois), available for preview on Google Books. Appalachian church records have been collected by the Family History Library, the Archives of Appalachia, Southern Appalachian Archives and many state and regional historical repositories. Published histories can be valuable sources of ethnic information, too; check WorldCat for titles such as:

- Welsh Founders of Pennsylvania by Thomas Allen Glenn (Clearfield Co.)

- Profiles of African Americans in Tennessee by Bobby L. Lovett and Linda T. Wynn (Annual Local Conference on Afro American Culture and History)

- History of the German Settlements and of the Lutheran Church in North and South Carolina by Gotthardt Dellman Bernhelm (Nabu Press)

- Coalfield Jews: An Appalachian History by Deborah Weiner (University of Illinois Press)

You’ll also want to consult the Images of America local history series by Arcadia Publishing. Search the website by keyword or ZIP code to track down titles such as African Americans of Jefferson County (West Virginia), Louisville’s Germantown and Schnitzelburg (Kentucky) and Jewish West Virginia.

Not all Appalachian ethnic groups remained separate. In fact, two distinct cultural groups grew from multiracial origins. The Melungeons of Tennessee and elsewhere are thought to have originated from whites, blacks, American Indians and Mediterraneans. (Cyndi’s List has a directory of Melungeon sources here.) The Pennsylvania Dutch, some of whom migrated south from the Keystone State, are thought to descend from Germans, Swiss and French Huguenots.

Oral Records

Until the 20th century, history was generally told rather than written in Appalachia. “As a general rule, mountain families didn’t keep journals or write letters up to a certain point,” Williams says, likely around the time of the Great Migration. “A lot of people didn’t leave any written evidence.”

Today, one of the best sources of Appalachian history is still storytelling. Since about the 1930s, interviewers have captured thousands of conversations on life in the hills and hollers, coal and logging camps, textile mills, railway yards and homes in Appalachia. Some of these memories — such as slave narratives — reach back into the 19th century. Others tell of daily life during the Great Depression, the Great Migration and the Civil Rights era.

Chances are, admittedly, not high that your own ancestor was interviewed. But Williams says tracking down stories is worth the effort if you can find an oral history from your family’s area. “You’d be surprised at what does get mentioned in these oral histories. People talk about their neighbors. You get into a little gossip — who married whom or who should have married whom.” You learn how people spoke, what they ate and what their working conditions were like.

Many oral history projects are available only through archives, via tapes or transcripts. The Eastern Kentucky Library Oral History Collection contains more than 3,000 interviews; find an index here. More than 500 interviews from the Appalachian Oral History Project are on file at Appalachian State University; see a description and index here.

You don’t have to look further than a good local library to read first-person accounts of Appalachia, though. Search Amazon.com or WorldCat on oral history Appalachia to find books on the subject, such as:

- Southern Appalachia: 1885-1915 by Roy Edwin Thomas (McFarland & Co.)

- Hard Times Cotton Mill Girls by Victoria Byerly (Cornell University Press)

- Our Appalachia: An Oral History edited by Laurel Shackelford and Bill Weinberg (University Press of Kentucky)

- Coal Hollow by Melanie and Ken Light (University of California Press)

Additionally, the Library of Congress has posted images of slave narratives collected during the 1930s. About 290 Appalachian residents are among those interviewed; find them here. For those who prefer to watch oral history rather than read it, Appalachia: A History of Mountains and People is an excellent PBS video documentary.

It may take a while to learn all you want to know about your Appalachian ancestors. For the most part, they lived modest lives and created only modest records.

But certainly the search for local sources is a fantastic excuse for a road trip through some of the most beautiful country in the United States. You may soon find yourself winding through hills and hollers, learning firsthand the powerful pull of the highlands and wondering how anyone could bear to leave them.

Tip: The Draper Manuscripts, a collection focused on the trans-Allegheny West from the 1740s to 1810s, is a good resource for early Appalachian ancestors. Many libraries have papers related to local areas on microfilm.

Native Blood

Many Appalachian families have Cherokee heritage, but they might not have talked about it much. Cherokee who remained in Appalachia after 1838 had done so by hiding. Fear of removal and then lingering social stigma led many families to keep their heritage quiet or invisible well into the 1900s.

Today you can trace your Cherokee blood through several sources. Cherokee who remained in Appalachia (“eastern”) and those who were exiled (“western”) are listed in various censuses and rolls taken from 1819 to 1924. Find indexes to these in Cherokee Roots, volumes 1 and 2, by Bob Blankenship (Cherokee Roots). The federal government created a wealth of records related to American Indians — learn where to find them at the National Archives and Records Administration.

Repositories Road Trip

Explore your family’s Appalachian past on this 600-mile road trip to your roots — or learn about these stellar collections online.

- Morgantown, WV: The West Virginia University Library Appalachian Collection has an outstanding collection on the 13-state Appalachian region, and much of it is indexed and annotated in the Appalachian Bibliography, published by the university. The collection has more than 9,000 volumes on topics ranging from coal miners to Cherokee Indians, as well as publications such as Appalachian Journal, Appalachian Heritage and the Journal of Appalachian Studies.

- Richmond, Ky: The Eastern Kentucky University Special Collections & Archives boasts a fantastic oral history collection (more than 3,000 interviews and recordings) as well as regional genealogical records, Appalachian studies resources, photographs, films, electronic records, maps and memorabilia relating to Kentucky history and literature.

- Berea, Ky.: Berea College’s Southern Appalachian Archives contains manuscripts, oral histories, photographs, records, tapes and films relating to the history of Appalachia and the surrounding community.

- Johnson City, Tenn.: The Center for Appalachian Studies and Services at East Tennessee State University includes the Archives of Appalachia. Look here for multimedia materials documenting the political, economic, social and cultural history of southern Appalachia. The Archive houses nearly 18 million manuscripts, 75,000 sound recordings and 250,000 photos and film clips.

- Boone, NC: The W.L. Eury Appalachian Collection at Appalachian State University’s Center for Appalachian Studies houses 37,000 books and more than 200 periodicals related to southern Appalachia. The extensive genealogical collection includes records on Native and African populations, censuses from 1790 to 1920 for all of Appalachia, a large regional newspaper clipping file, photographs, maps, and family and local histories.