When John Donne said “no man is an island,” he could have been describing family historians with Rhode Island roots. This tiniest of US states — measuring a mere 37×48 miles — boasts an inversely proportional genealogical bounty. From Providence to Pawtucket, you’ll find family history tools at every turn.

In fact, the Ocean State offers so many research opportunities; you might feel adrift in a sea of records, finding aids, Web sites and more. But don’t let that tidal wave of resources capsize your genealogical ship: Follow our advice to coast to new family tree finds.

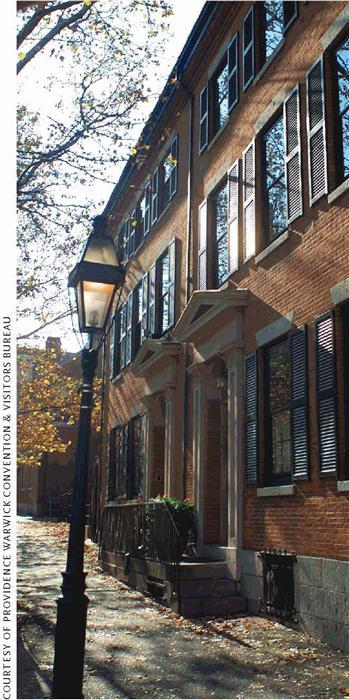

Harboring history

Rhode Island’s voyage began in Providence, which a group of religious and political dissenters from Massachusetts, led by Roger Williams, founded in 1636. Two years later, exiled Bostonians established Portsmouth on land they bought from the Narragansett Indians.

Dissent became a theme of Rhode Island’s early years. Soon after Portsmouth popped up, internal rifts led some residents to create new settlements at Newport and Warwick. Once Williams acquired a patent for the colony in 1643, the towns spent four years forging a common government: a loose confederation continually threatened by infighting and takeover by other New England colonies until 1663, when John Clarke received a royal charter. Rhode Island colonists carried out the first act of aggression against the British crown — burning the customs ship Gaspee in 1772 — but they were the last to ratify the US Constitution, in 1790.

Making landfall

Those ongoing political disputes led to boundary changes that could affect your research. Some Rhode Island cities — including Bristol and Warren, annexed in 1747, and part of Pawtucket, acquired in 1862 — were originally in Massachusetts. If your kin lived in a border town, you’ll want to check for records in neighboring states, too.

The Ocean State’s multitude of tiny villages also can make it tough to track your clan. For help, consult old maps, such as the 1895 Rand McNally map at <fermi.jhuapl.edu/states/1895/ri_ 1895.jpg>, and geographical dictionaries. In particular, see the 1819 Gazetteer of the States of Connecticut and Rhode Island, available on microfilm via interlibrary loan, and online at Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > (subscription required) and in Heritage-Quest Online’s <heritagequestonline.com> book collection (access it via a subscribing library).

You shouldn’t find it tricky to track your ancestors’ territorial transfers: Land records date to Rhode Island’s earliest Colonial days. The initial documents, called land evidences, reside in their original form at the Rhode Island State Archives (see resources); you can rent the microfilm from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> for viewing at a branch Family History Center.

The state archives also has records of town proprietors’ land sales to individuals, other land grants, and a card index covering land records from 1648 to 1776. Town clerks recorded subsequent land transactions. You’ll find microfilmed Rhode Island town records in repositories including the FHL, New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS), state archives and Rhode Island Historical Society (RIHS). See the resources for these repositories’ contact information.

Fishing for town records

Town clerks kept tabs on far more than land sales: As in other New England states, most Rhode Island recordkeeping occurred at the town rather than the county level. Typically, documents stretch back to a burg’s beginnings — for the state’s four original cities, that’s the 1630s. You’ll find a listing of other locales in NEHGS’ Rhode Island town guide (go to <www.newenglandancestors.org/research/reference> and click the state name).

Of particular genealogical interest, of course, are vital records, also found among the town-records microfilm trove. The catch: Except for Providence, towns didn’t create comprehensive name indexes. Plenty of other finding aids exist, though. Start with James N. Arnold’s 21-volume Vital Record of Rhode Island 1636-1850: A Family Register for the People (Narragansett Historical Publishing), available on CD, on FHL microfilm and in NEHGS’ members-only online databases ($75 per year).

For births, marriages and deaths after 1853 — when state-level vital-record-keeping began — contact the state health department (see resources). Ancestry.com’s Rhode Island Vital Records: 1636-1930 CD serves as an index to those records.

The other exception to the town-records rule: court proceedings. Look for those at the state Supreme Court Judicial Records Center, listed in the resources section.

Harpooning head counts

As one of the 13 original Colonies, Rhode Island was part of the federal government’s initial census of 1790, and has participated in every decennial head count since. Access them on microfilm at genealogical libraries, the FHL or the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov>; they’re also online at Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest. The only US census records you can’t get for Rhode Island are for 1890: Most of that enumeration burned, but the state’s schedules of Civil War Union veterans and widows escaped the blaze.

You’ll also find a deep pool of state and Colonial censuses. Ocean State enumerations, which happened every 10 years from 1865 to 1935 (the 1935 count took place in 1936), supplement the federal records. Except for the missing 1895 census, they’re available at the state archives and on FHL microfilm.

Five Colonial head counts have survived, beginning with a 1730 head-of-household list. The colony enumerated heads of household again in 1774 and 1782; it also took a 1747 list of freemen (property-owning males age 21 or older) and a 1777 military census (covering males 16 and over). The state archives and RIHS hold the original records, but you’ll want to consult printed transcriptions first — we’ve listed a few in the resources section. For more on early head counts, see Maureen A. Taylor’s article “Rhode Island Colonial Population Estimates” on the NEHGS Web site (go to <www.newenglandancestors.org/education/articles> and click Rhode Island, then the article title).

Riding immigration waves

Although Boston was New England’s primary immigration port, several of Rhode Island’s seaside cities saw significant immigrant traffic. NARA and the FHL have microfilmed passenger lists for Providence (1820 to 1872), Newport (1820 to 1857), and Bristol and Warren (1820 to 1871); RIHS has the originals. Ireland supplied the most 19th-century newcomers, and French Canadians flocked to the Ocean State after the Civil War. Later, Southern and Eastern Europeans — especially Italians, but also Poles and Russian Jews — arrived during America’s “great wave” of immigration.

After the 1798 Alien and Sedition Act passed, Providence customs officials went beyond the letter of the law, recording all incoming immigrants, travelers and merchants from 1798 to 1808. Look for records at RIHS.

During the Colonial period, Rhode Island’s reputation for religious tolerance and liberal politics attracted such minorities as French Huguenots, free blacks and Jews, though the bulk of early Rhode Islanders were English Protestants. To trace early colonists’ origins, take advantage of published works such as Genealogies of Rhode Island Families: From Rhode Island Periodicals, the pioneering compilation of Ocean State lineages. Many libraries have copies have these out-of-print volumes. Other classics: the similarly titled Genealogies of Rhode Island Families From the New England Historical and Genealogical Register (Genealogical Publishing Co.) and John O. Austin’s Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island (see resources).

Because of religion-spurred migration, church records also may be helpful. In particular, many early settlers belonged to the Society of Friends (aka the Quaker church), which kept detailed records. You’ll need to check the denomination’s archives — see the Rhode Island Research Outline at Family Search for contact information.

Naturally, the sources described here only skim the surface: You also have a bottomless well of military records, wills and probate files, naturalizations, newspapers, periodicals and other sources to wade through. See <www.rigensoc.org/rigenealogyfaqs.htm>, <rootsweb.com/~rigenweb/ri-research.html> and our recommended resources to dive into deeper record details — and cruise to genealogical success.

From the October 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.